The utility industry entered the commercial drone game early, enabling quicker expansion into more applications.

In the nearly 10 years since Dominion Energy first began deploying drones, the team has built up more than 150 use cases—and Nate Robie, manager of the Unmanned Systems Group, expects that number will continue to grow.

Robie describes drones as a workforce multiplier, increasing safety and enhancing efficiencies for both inspections and operations. The technology is a key part of the industry-wide effort to make the bulk power system more reliable, with asset inspection a main focus.

Drones, typically carrying RGB, thermal or LiDAR payloads, are looking for defects in boiler tanks at power generation facilities, detecting radiation interference at substations, identifying anomalies on transmission poles and monitoring vegetation encroachment in right of ways, to name a few routine applications. Reports and repair orders are generated based on what’s discovered during the flights, helping utilities better maintain their equipment and ultimately prevent outages.

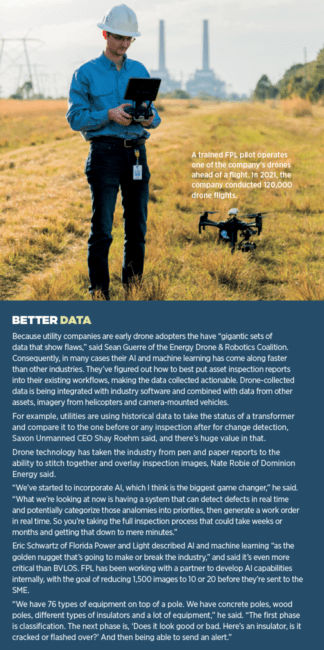

Because utilities were early adopters—many of the big players have had programs for upwards of five years—there’s been a recent expansion of drone use at scale, said Sean Guerre, executive director of the Energy Drone & Robotics Coalition. The number of linemen cross-trained as pilots deploying drones in their daily operations has significantly grown, with many utilities offering vigorous training and certification programs. There’s a high comfort level with the technology and an understanding of what it can do for the industry, particularly as we move toward more automation and a regulatory framework for BVLOS flights.

As drone adoption continues to grow across the industry, so too does the opportunity for new use cases. In recent years, UAS have been deployed for rope pulling, as part of wildfire prevention programs and as surveying tools for environmental monitoring. More complex applications, such as attaching equipment from a drone to a power line, have also become possible.

“It’s not just accepted in the industry, said Corey Hitchcock, program lead at Southern Company. “It’s almost expected.”

POWER GENERATION

Drones are now more routinely being flown for inspections inside power generation facilities, gathering data in confined spaces and GPS-denied environments, Guerre said. The systems can help spot various defects, from flaws in pump valves to corrosion inside a vessel, allowing them to better predict when it’s time to take an asset out of service for repair, or to replace it.

“It’s not just accepted in the industry. It’s almost expected.”

Corey Hitchcock, UAS program lead, Southern Company

Southern Company is starting to do more drone work in radiological containment areas, Hitchcock said, performing inspections in the “deep, dark places” inside power plants so humans don’t have to. This not only enhances safety, particularly in nuclear power plants where radiation dose is a concern, it also eliminates the costs associated with erecting scaffolding and equipment downtime.

“If something breaks at a power plant and has to come offline, you’re not generating electricity, which isn’t good for companies whose business it is to sell electricity,” Hitchcock said. “In the past, we had to wait several days for a boiler to cool and to build scaffolding. With a drone, we can identify or rule out problems, saving us a lot of time and allowing us to get the right part.”

Repairs are made faster, shortening outages, and scaffolding can be contained to just the area that needs repaired, rather than covering the entire asset.

This response has been made easier with the Elios 3 from Flyability, Hitchcock said, which uses LiDAR point clouds to navigate once it’s inside a boiler. Before, a drone could collect imagery and video to identify flaws, but it couldn’t tell the operator exactly where those flaws were. Now, they can fly the drone and model at the same time, what Hitchcock describes as a game changer.

Drones are also being deployed to perform inspections after radiation leaks, Hitchcock said. In fact, it’s now the go-to tool, where it was once an afterthought.

Dominion relies on UAS for boiler inspections as well, with the technology also leveraged to inspect infrastructure outside power-generation facilities, Robie said. Construction monitoring, water tower inspections and volumetric measurements are among other applications. They use both quadcopters to hover for close inspections and fixed-wing drones to map large areas.

Dominion recently received a waiver from the FAA that covers more than 40 facilities across seven states, allowing the team to fly the Skydio X2 drone BVLOS without an additional crew member or technology to detect other aircraft. Skydio’s AI technology makes it possible to fly the drone closer to structures, enhancing the data obtained during inspections.

Drones also can deployed for inspections at hydroelectric facilities or dams, said James Pierce, manager of UAS and inspections for Ameren. And the company isn’t just responsible for the dam; it also must maintain shoreline permitting around the reservoir. UAS provide detailed inspections that assist with that activity.

Other robotics, such as crawlers and rovers, are finding their place at these facilities as well, Guerre said. They can perform inspections on a variety of assets in a set, repeatable pattern, as well as examine a perimeter around the plant as a means of security.

Drones and ground robotics can be used in combination, Guerre said, for more efficient inspections. A crawler might be deployed to handle a boiler inspection, while a quadruped robot is sent to look for corrosion on internal pipelines and the drone checks for flaws on a stack.

Submersibles also play a role, Robie said, and can be deployed on a dam, for example, to gauge soil sediment or inspect the infrastructure. They can be used inside water-holding tanks or other liquid holding vessels as well.

Energy companies are also leveraging robotics for their renewable assets, deploying crawlers designed specifically for wind turbine inspection and to monitor solar panel operations, as examples.

DISTRIBUTION AND TRANSMISSION

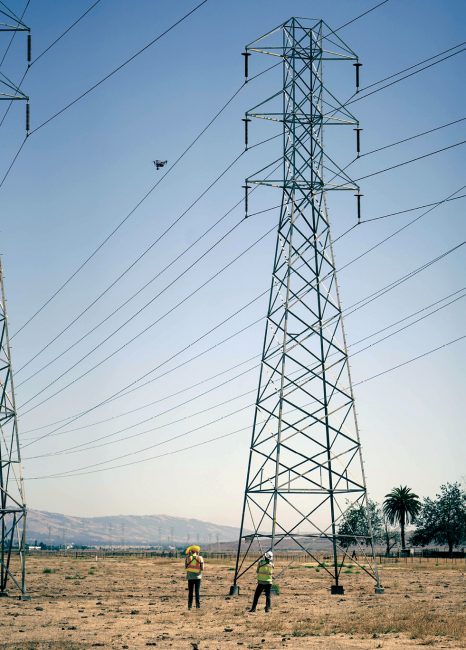

Drones have become a key enabling technology for scaling power grid inspection services across transmission and distribution lines, which span thousands of kilometers, including assessing the condition of substations, Cyberhawk Chief Revenue Officer Patrick Saracco said.

Substation buildings are large and difficult to access, U.K.-based National Grid Condition Monitoring Manager Mark Simmons said, so deploying drones to inspect them makes sense. Drones can fly overhead rather than crews having to work via elevated platforms.

Typically, asset managers are looking for radio frequency interference (RFI) during these inspections, Simmons said, because it indicates equipment is in distress. A specialized payload must be flown on the drone to detect RFI and locate its source.

National Grid is also involved in a project to develop a payload for live insulator testing across both substations and overhead lines, Simmons said. This application helps avoid system outages while also providing a bigger sample size.

Encroachment is another area drones can address, Guerre said, whether it’s monitoring vegetation to ensure it’s not contacting lines, which could lead to outages or spark a wildfire, or serving as security to make sure nothing is in the right of way that doesn’t belong.

Then there are the transmission towers. Drones can look for corrosion or any type of flaw around a transformer, Guerre said, such as the way the line and equipment attaches to the pole or broken screws.

Drones can provide an in-depth look at each individual structure, Robie said, and the various components. Frayed lines, chipped or cracked insulators, broken cotter keys and rust are among the many deficiencies they spot.

The Ameren UAS team primarily provides imagery and infrared analysis for state-mandated pole inspections in Missouri, Pierce said, covering more than a million poles on four to six year cycles.

“We fly 120,000 poles a year, producing inspection reports which eventually take the form of work orders to address any reliability issues discovered,” Pierce said. “We do similar inspections for our transmission company. We use UAS to ensure reliability and prevent outages, flying different shot patterns and covering long stretches of corridor.”

Before drones, National Grid relied on helicopters for these types of inspections, like other energy companies, but the challenge was the aircraft couldn’t get everywhere because of proximity to buildings or livestock, missing 10 to 15% of the assets, Simmons said. There are no right of ways in the U.K., so it’s common for livestock—particularly horses and sheep—to roam in the field under towers. The company started using drones to address this challenge in 2017.

Inspection and survey, Simmons said, are the primary reason for most flights, flying high-end cameras, radar, vision optical sensors and infrared cameras. The technology has come a long way in just five years, now enabling UAS to follow automated flight paths, build a 3D way point, fly a tower and then fly the exact same path on a different day. The goal is to not only look for various defects that could lead to issues, but to determine where the assets are on the end of life curve to work out the optimum time to not only replace individual components, but entire assets.

Florida Power and Light (FPL) began its drone program in 2016, using the technology as a tool to help them work safer and smarter, said Eric Schwartz, manager of technology and innovation for FPLAir, the company’s drone program. Poles and wires are among the items on the inspection list, moving from crews driving along looking up at lines to spot defects to the aerial perspective drones provide.

“In the poles and wires business, drones have revolutionized how we do our assessments and allowed us to be more precise.”

James Pierce, manager, UAS and inspections, Ameren

“They were really only assessing one quadrant out of the entire pole because they couldn’t get up on top and look down, and they weren’t looking from the other side of the neighborhood or block,” Schwartz said. “In the poles and wires business, drones have revolutionized how we do our assessments and allowed us to be more precise.”

The team flies thermal and RGB sensors looking for cracks, corrosion from salt spray, termite damage, pole rot and hot spots that indicate there’s risk of an outage, he added.

Crews no longer have to regularly walk in backyards or drive along roads to find the damaged components, weathering and broken poles that could lead to outages, Pierce said. Drones can quickly identify defects so operators create work orders and prioritize repairs.

“When drones became an option for us in 2016, we proved you can capture so much more data from above, looking down,” he said. “A lot of problems are on the top of the pole. That’s where the weather hits, like snow sitting on top of a pole. That’s readily visible from above. And the detail drones provide have had amazing results as far as reliability of the system is concerned.”

STORM RESPONSE

Drones have also found their place in storm response, allowing utilities to quickly find damage and start repairs. Emergency response caught on quicky after the 2017 hurricane season, which included Irma in Florida, Schwartz said, and has become routine.

A lot of the work is done before a storm makes landfall. Drones can map an area in good weather, and then be sent out to map it again after a storm, Southern Company’s Hitchcock said. Change detection software can show crews exactly where they need to be and the equipment they need to bring.

LiDAR is also being flown for pole and wire assessment pre-storm, with FPL leveraging the technology for hardening. The company is a leader in a program that started after the 2004/2005 hurricane season. The goal was to redesign the entire system of lines on the distribution side to withstand 150 mph plus winds.

“When poles go down, it’s the longest bottleneck and lead time to get electricity back on,” Schwartz said. “It’s easier to put wire back up. Flying LiDAR helps with pre-engineering to get a better understanding for design and redesign jobs.”

FPL’s newest drone, FPLAir One, is designed for these and other large-scale flights. The fixed-wing drone is the size of a small aircraft, can fly up to 1,000 miles and operate in tropical storm-force winds.

The team plans to fly the drone to create a 3D twin of the entire state, and then use the drone in a box solution from Percepto to look at the distribution network and overhead lines for pre-engineering of the hardening program, Schwartz said. AI will be leveraged for change detection.

Pulling rope is another application born out of storm response.

“You can use a drone to pull rope when you need to get a power line across an obstacle, maybe water or other terrain,” Hitchcock said, noting Southern Company uses a rope release mechanism designed in-house. “That practice was developed in the mountains of Puerto Rico during hurricane Maria.”

THE FUTURE

As the technology continues to advance, standardized inspections will become more automated, Simmons said. Remote pilot inspections will become the norm, with complete autonomy on the horizon.

Hitchcock sees drone in a box solutions standing by at facilities like substations, and UAS eventually replacing helicopter patrols for linear inspections.

“You’ll still see some manual operations, but with a drone in a box solution on board a majority of our post-events will be done autonomously,” he said. “As the substation or distribution operation sees the call come across the consul, the drone will already be online trying to determine what caused the problem.”

“When drones became an option for us in 2016, we proved you can capture so much more data from above, looking down.”

James Pierce, manager, UAS and inspections, Ameren

Utilities are also starting to look into corona ultraviolet detection sensors that can tell if electrical connections are not configured efficiently, Pierce said.Methane is another area of interest in the proof of concept stage, Robie said.

More intrusive inspections are starting to come online as well, including developing a sensor that allows testing on insulators on overhead lines while they’re live, Simmons said. Crews would have to be onsite to operate these types of specialist sensors, but most other inspections will still happen remotely.

Large scale, high-endurance UAS will continue to become more cost-effective, Schwartz said, making highly autonomous BVLOS flights more feasible. Drone in a box solutions will handle the granular level cracks and fractures, zooming in on equipment like insulators.

Alternative fuel sources, such as hydrogen, are also in play, Robie said, as the industry looks to continue to improve efficiencies and ultimately the power system with the help of drones.

“What we’d like to do is be able to cover more of our footprint and inspect various assets in one flight rather than going from an electric transmission right of way to another mission in a solar field,” he said. “The goal is to have one flight where we can inspect various infrastructure to get that data to the multiple businesses we service quicker.”