In-house and Outsourced Business Models Maximize Utilities’ Drone Use

Utility companies are using a wide variety of drone service models, from operating in-house fleets to contracting out drone services, and everything in between. All of the models have their pros and cons.

Double-Zooming?

Corey Hitchcock, UAS program lead for Southern Company, was talking from Alabama via Zoom to describe how the gas and electric utility deploys its massive drone fleet. Simultaneously, a Southern drone was zooming around for a shoreline inspection supporting a forthcoming hydro project.

Utilities are getting busy with UAS. Drones often offer better, safer and cheaper results than manned or ground asset inspection and mapping. As drone solutions provider Spright notes, they can discover 20% more critical finds than traditional methods, can scan three towers as fast as a climber can do one, and use up to 87% less manpower and resources per mile inspected.

But utility deployment models vary widely based on a program’s maturity, capability and financial wherewithal.

“We try to do as much as we can in-house,” Hitchcock said about the depth provided by Southern’s massive, 380-or-so strong drone fleet. Other utilities blend in-house operations with outside providers’ specialty sensor and data solutions.

And some utilities prefer outsourcing. “Right now, we do not do much with drones,” a spokesperson for a regional provider emailed, “and when we do, it’s usually through one of our contract partners with a very specific focus. That may change in the future, but for now, it’s not.”

“We take them from cradle to grave,” CEO Frank Segarra said about the end-to-end services his ConnexiCore company offers entry-level utilities.

Insights from utility leads, vendor executives and an association CEO detail how varying utility and provider business models use UAS to keep the lights on.

MAPPING THE MODELS

As both managing director of Innovate Energy and director of the Energy Drone & Robotics Coalition, Sean Guerre knows the scope of the power and utility sector’s drone use. “Adoption has grown exponentially,” he said from Houston. “It’s the biggest today, and it’s projected to be the biggest in five years. Whether survey, mapping, inspections, there’s a ton of use cases.”

Declaring himself to be a neutral “Switzerland,” Guerre detailed the pros and cons each paradigm provides.

In-house, “you’re able to control the program, the quality—that’s the number one advantage. It allows you to scale a certain level that you’re comfortable with because you’re doing the use cases in-house and determining how that will impact the rest of your operations.” Vetting equipment and payloads, ensuring pilot qualification, controlling how data is analyzed—“that’s all being monitored by your own team.”

But in-house isn’t a panacea, Guerre added. “The disadvantage of in-house is, obviously, you have to build it yourself.” Responsibility, liability and cost also come into play. “You have to purchase and maintain all the equipment, and when you get new models, that capital cost [CapEx] is coming back to your program.”

Blended/hybrid programs let utilities use their own strengths and those of others as well, especially when demand escalates. Guerre said, “They may have in-house working on regular projects and programs, but outsource allows you to scale very quickly, for a large project or an incident.”

On the other hand, Guerre said, managing both multiple outsource contractors and in-house personnel can be “a big challenge. You can say I’m getting the best of both worlds. You could say, I’m getting the worst of both.”

End-to-end outsourcing, Guerre said, can educate newbie utilities or augment those with limited resources. “You’re not having to retain the equipment, which can evolve very rapidly,” Guerre noted. “You’re paying [providers] to get your data. Some will go all the way through so you don’t even have to have analysts.”

Across the business models, specialty providers can deliver valuable targeted data—if correctly integrated. “The MSA, or master service agreement, will be very specific with emergency people that are pre-vetted,” Guerre said. “When you’re flying near high voltage, that stuff is really into billions of dollars.”

Let’s look at implementation and use cases across these models.

IN-HOUSE

“The in-house operation allows us to more closely control the quality of work,” Hitchcock said about Southern’s drone use. “We have an SME [subject matter expert] in-house, where it’s for concrete inspections, powerline patrol, land management, nuclear inspection. I feel that we can always do it at a better price point.”

Southern, unlike less scalable companies, is expanding its number of in-house drone types and specific solutions to meet defined UAS use.

“There are three different ways you can operate a drone at Southern,” Hitchcock said. “We have a self-dispatch model in support of day-to-day business units—a person in the company that has another job that does not directly report to corporate. Their job isn’t to fly drones every day; they need a drone to look over something.” Self-dispatch drones operate at less than 10 pounds for basic operators, less than 20 pounds for intermediates.

“Then, for more advanced drone operations, we have our in-house team inside the corporate aviation department.” These operators can work within the full authority of Part 107.

“We try to do as much as we can in-house, with contractors on the edge. We’ve had a few inspections, but most are supporting things like engineering contracts for the company.”

Hitchcock noted an important consideration: “All of our customers are internal customers, within the different operating companies. We are Southern Company Services, and we work closely with leadership to make sure that our efforts are aligned. We find out what they need and figure out how to capture the data or problem. We keep our finger on the pulse of the industry and when somebody comes up with a different use case or application, we’re able to point them in the right direction.”

A Corporate Aviation Department governs the UAS program, and Hitchcock cited that as a success factor in “our ability to interact with the FAA.

“We ultimately provide value and safe money in the long run,” he said. Using outside solutions can require vetting, deadline management and standardization. “Being in-house, I think, is overall a better value for the company.”

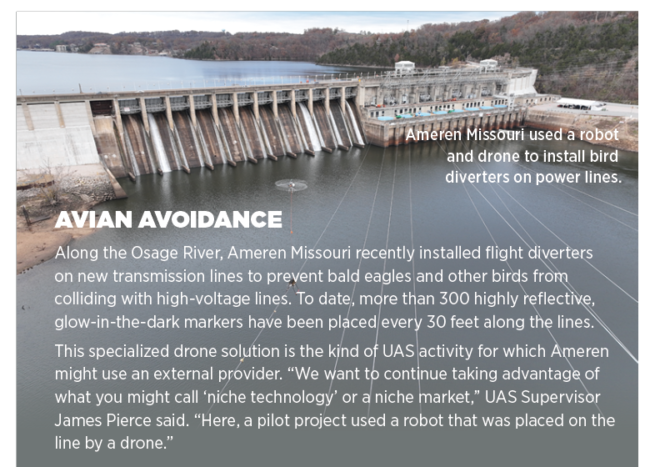

Ameren Missouri also makes a major commitment to in-house UAS. With 800,000 poles across 25,600 overhead circuit miles, its 160 drones help ensure service to more than 2 million customers. Asset inspection with multiple sensors is foremost, but use cases can range from vegetation assessment to locating beehives on rights of way.

“We are mostly an inside utility drone provider, about 90%,” said James Pierce, the supervisor of UAS operations. Pierce cited quick response time, cost control and lowered risk to personnel as key in-house advantages.

“In-house, we know exactly what the costs and time are for each activity. For emergency situations, we can get data back to them the same day, fully reviewed by us. Contracting to get someone there takes markedly longer. It always comes down to customer first.”

Pierce detailed Ameren’s in-house business model. As with Southern, all of Ameren’s “data requesters” are internal. Ameren doesn’t fly manned aircraft, so it doesn’t have an internal aviation department. Rather, an Ameren Services Group began under the company’s transmission organization and has been a budgeted department under corporate for six years. An in-house sourcing group tracks vendors. “We vet and clear all our drones through controlled supplier systems for warrantees and insurance and protection.”

Ameren’s in-house capabilities are expanding to meet new needs. “Solar is going to be a huge part of our portfolio, and the drones are becoming integral to providing many stakeholders a view of what’s happening from the greenfield all the way to when things are finalized,” he said.

BLENDED/HYBRID

Even major in-house utilities may face high demand or special needs. “Most of the time, we do the analysis of data ourselves,” Pierce said. But, he added, “there are other activities where we can provide the data and that [outside] company can do the analysis to produce the piece needed to do the job.” Also, he noted, some engineering functions require licensed surveyors to certify that data is exact.

Blended models can provide research and development, especially for entry-level utilities. “A lot of utilities like drones as a service because they get to try you out before they make a large investment,” said Eileen Lockhart of drone solutions provider Spright. “They may want to test your capabilities or see if you’re a good fit.”

Lockhart is herself something of a hybrid. After a decade with Xcel Energy, including six years as UAS program lead, she recently joined “drone solutions provider” Spright, launched by Air Methods in 2021, as director of customer experience and utilities services. “I had the pleasure of really understanding those use cases, and really quantifying the cost-benefit analysis,” she said from Denver. “Now, on the vendor side, I can help more utilities.”

Spright specializes in end-to-end innovative technologies across utilities (and health care) while leveraging its parent company’s aviation expertise. “The aircraft that we have for our utilities were actually built for utilities, custom-designed and built for industrial applications,” she said. About 20 drones operate on the utility side, with several more on order, and an over-55-pound version is currently undergoing type certification by the FAA. “We’ll increase with demand.”

Whether providing custom solutions for developed programs or consulting to in-house startups, Lockhart likes the blended-utility model.

“You get the best of both worlds. I think it’s very smart that they have certain people certified to operate in demand-type situations to enhance safety. And I think it’s very smart to outsource to professional aviators that understand the technology for the larger jobs they may not have enough bandwidth to support,” she said. “We figure out what you actually need and then we customize or tailor our solution to fit that. Utilities want to work with professional organizations that know what they’re doing.”

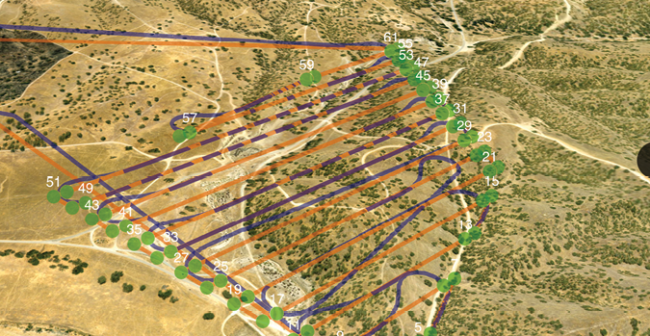

SkySkopes defines itself as a “professional end-to-end data collection and remote sensing organization,” with processing and GIS back-ends. “A lot of times people come to us for cutting-edge and complex operations,” founder and partner Matt Dunlevy said from Grand Forks, North Dakota. SkySkopes has been in business since 2014, and a major utility with 100 in-house pilots contracted it for “the first transmission line streaming operation in the United States.”

And now? Being in “the business of using data collection techniques,” Dunlevy said, “they’ll come to us because we’ve had the first glimpse into the value. They’ll bring us in to test it out or have an audition. We want to explain to them that we’ve already hit the road running so there’s no need to reinvent the wheel.

“You get instant scale. You instantly broaden your pilot bench, you instantly broaden your available assets.”

SPECIALIZED SOLUTIONS

Whatever the utility business model, niche players can address specific situations.

The founder of Swiss-based Auterion developed the PX4 open-source flight controller some 15 years ago. Now, Auterion’s mission is to provide one ground control to data processing operating system and user experience for many types of drones, freeing users from any one company’s product development decisions and need to relearn multiple iterations.

“At the heart, we’re a software company that is really focused on standardizing and data end-to-end workflows,” Senior Vice President Romeo Durscher said. “We provide the data pipeline: one data workflow, from capturing the data to getting the data in whatever end product you want.”

PX4 is an open-source ecosystem where 11,000 contributors can collaborate on software solutions. “We do, in essence, the final touches. We create a user-friendly experience, and then we have software on the flight controller side, as well as the operations side, that is intuitive, standardized,” he said. “We bring our whole software suite into the picture to provide that needed insight into your operations and data management. That’s the value proposition.”

The idea is to use data, not to be used by it. “Pretty much 90% of data that is being captured is useless,” Durscher said. “You are only looking for the 10% actionable data, and it takes so much time. We’re enhancing the efficiency.” One Swiss utility has improved its efficiency by 40%, Durscher said. “So, from the user perspective, this technology saves work time, it mitigates risk and it improves the output.”

Raptor Maps is another specialty provider, offering advanced analytics and productivity software across the entire solar lifecycle. Last June, Don Nista became head of knowledge for the Somerville, Massachusetts-headquartered company, bringing almost a decade of leading operations and maintenance for utility-scale solar.

Per drops in the levelized cost of energy, “we’re seeing utilities more aggressively entering the space,” Nista said from Denver. “Where Raptor Maps really shines is making sense of mapping and creating usable reports out of very large datasets. Raptor Maps’ specialty is to supercharge scans to create digital twins of the anomalies and the finding, and help get things sorted.”

Identified issues can range from an entire inverter being offline down to the level of panels, sub-panels and cells. Recommendations suggest prioritization and budgeting. “It’s really useful to utilize our technology to understand the full health of your system,” Nista said.

FUTURE MODELS

Asked to describe the scenario for UAS and utilities three years from now, opinions coalesced around increased adoption by small utilities, simplified analytics, evolving autonomy and a hope for the FAA to relax height and BVLOS restrictions.

The overarching hope was voiced by Guerre: “Better data faster.”