Delivery drones are making an impact, safely transporting critical medical supplies to remote areas, hot lunches and goods to people’s homes, blood samples to hospitals, and spare parts and other materials to workers on jobsites. But delivery areas are limited and the focus is now on expanding operations to unlock the true value delivery drones can provide.

For some, having groceries delivered via drone is about convenience. Their package arrives in minutes, whether it contains a missing ingredient for that night’s dinner or medicine to soothe a lingering cough. In the work environment, drone deliveries can improve efficiencies and lower costs, quickly getting critical tools where they’re needed to minimize downtime. And in many cases, delivery drones are saving lives, bringing medicine and vaccines to remote areas that don’t have easy access to medical supplies or even common household items.

These platforms are starting to make an impact in many areas, advancing from the testing stages to a viable delivery alternative. They’ve already proven their worth for medical deliveries, with Zipline and its fixed wing all-electric vehicles the trailblazers that started with blood deliveries in Africa. Others, like Spright, Drone Delivery Canada (DDC) and Wingcopter, are now deploying drones to transport blood samples, laboratory diagnostic materials and medicine.

Such delivery applications, as well as worksite deliveries, will continue to improve and expand, but there’s also now a push toward the ultimate goal: scaling the residential package deliveries that come with more regulatory challenges. Some communities can already order food and various small goods through a delivery app, but it’s limited. For drone delivery to reach its full potential, more people need access to the technology.

“The next piece is how do you turn this into a profitable business model?” said Chenlu Qiao, strategic marketing manager with Trimble Applanix. “Delivery operators have to determine how to increase efficiency and how to serve more customers. Increasing efficiency happens through workflow automation, so we’re seeing operators trying to bring drones closer to the warehouses.”

BVLOS operations and the ability to fly over densely populated areas will make it possible to serve more customers, Qiao said, and will be huge in moving residential package delivery forward.

A boost in unmanned aircraft receiving Part 135 certification from the FAA is also required to scale, said Tombo Jones, director of the Virginia Tech Mid Atlantic Aviation Partnership (MAAP). MAAP partner Wing was the first to do so, allowing for BVLOS deliveries and paving the way for other drone delivery companies. But such certification is difficult to obtain, and only a few others have followed suit.

While progress is slow, it is being made, with those involved with drone delivery all too aware of the many benefits it can provide once scaled. Leveraging the technology can save lives, alleviate road congestion, improve efficiencies on worksites and reduce pollution. But it’s going to take some work to get there.

“For drone delivery to truly scale, the industry will need to move to more autonomous ecosystems,” A2Z Drone Delivery CEO Aaron Zhang said. “There are a lot of technologies that need to work together seamlessly for truly autonomous drone delivery to happen. Of course, regulatory evolutions will be needed to reach those benchmarks as well.”

MEDICAL DELIVERIES: THE FOUNDATION

With medical drone deliveries, where it all started, the main goal isn’t to make a profit. It’s to save lives. Drones can deliver critical items like vaccines, medicine, samples, blood and medical equipment faster than traditional methods, especially when those items are needed in remote locations.

Wingcopter is among the companies focused in this area, and while they’re starting to test grocery delivery as well, medical will remain the priority. The company recently signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Siemens Healthineers Middle East, Southern & Eastern Africa to develop an integrated drone delivery solution to transport various laboratory diagnostics materials as well as other medical supplies in Africa.

The battery powered drones will cover a range of 75 kilometers, maintaining the cold chain at all times. The service will centralize sample testing and medical goods distribution, ultimately increasing efficiency and reducing costs, CEO and cofounder Tom Plümmer said.

Wingcopter also established regular and emergency delivery service in the district of Kasungu in rural Malawi, flying drones to replenish stockouts of essential medicines and other medical commodities in two health centers.

Spright, which is on the path to type certification, also has chosen medical as a focus, said Bill Wimberley, vice president of strategic programs. In many cases, these life-saving deliveries go from point A to point B and back again, say between medical facilities, minimizing the risk involved and making it easier for the FAA to grant BVLOS waivers. And cost is less of a factor; for these deliveries, it’s about improving and saving lives.

But, of course, medical deliveries also come with challenges. Drones must be equipped to carry hazardous materials and there’s also chain of custody. Spright is experimenting with an autonomous landing system that eliminates the need for a nurse to come to the parking lot to pick up a package to address that issue.

“The drone lands on the box and the box recognizes the drone and package,” Wimberley said, noting this could be via a QR code or another system. “The automatic arm then comes up from the box, grabs the package autonomously, stores it and notifies the appropriate person that they have a sample to pick up.”

How items are packaged is also critical, Wimberley said, as medications and samples often must stay at a certain temperature. A lab Spright works with uses a box about the size of a lunchbox, with a slot on the side for dry ice, as standard packaging for sample delivery, for example. The company had to determine how to attach it to the drone without changing the temperature or adding vibrations that could harm samples like blood.

The way medical delivery drones release packages is varied and continually improving. Zipline’s “Zips,” for example, have been delivering blood in places like Rwanda for years, with all parts of the deliveries handled autonomously. In the beginning, the company’s flight planning software used simple ballistics calculation to determine when to release packages at the delivery site, CTO and cofounder Keenan Wryobek said, but have since layered in compute that accounts for the inflation properties of parachutes. They’ve redesigned the parachutes for more precise delivery. The software takes into account many factors including real-time wind speed measurements.

DDC, logistics company DSV Air & Sea Inc. Canada and Halton Healthcare Services partnered to deploy DDC’s drone delivery solution, establishing a transportation link for Oakville Trafalgar Memorial Hospital. Drones travel from DDC’s DroneSpot takeoff and landing infrastructure to deliver medical isotopes, CEO Steve Magirias said. The company has also completed First Nation delivery projects, setting up DroneSpots in villages to transport medical goods to these communities, many of which typically rely on boats.

A2Z is seeing an uptick in medical deliveries for first aid, Zhang said. One customer, for example, is transporting emergency defibrillators that can meet first responders on the scene, while another is using the company’s tethered delivery method to trial remote guided medical treatment for search and rescue operations.

The Rapid Delivery System (RDS2) drone winch is the “hallmark” of A2Z’s delivery method, Zhang said. When the drone arrives at its delivery location, the winch precisely lowers the package to the ground. The winch features several redundant safety mechanisms, including an active payload monitoring system and a passive payload lock that keeps the tether from unspooling if there’s power loss. The tether can be deployed automatically or manually.

The winch is integrated into A2Z’s drones but also can be added to most other airframes. Because it delivers from altitude, pilots can maintain line of sight throughout the flight. The auto-release mechanism releases the package as it touches down, so there’s no need for someone to pick up the package or interact with the drone, improving safety and efficiencies.

Regardless of the method used to release these critical packages, many think medical will make up the bulk of drone deliveries for the foreseeable future—making a huge impact on people’s lives.

BACKYARD DELIVERIES

Residential package delivery will be more difficult to accomplish. Instead of flying from point A to point B and back over and over, drones must pick up orders from a location near the restaurant or retailer and then take it to a home that could be located anywhere in the community served, flying BVLOS.

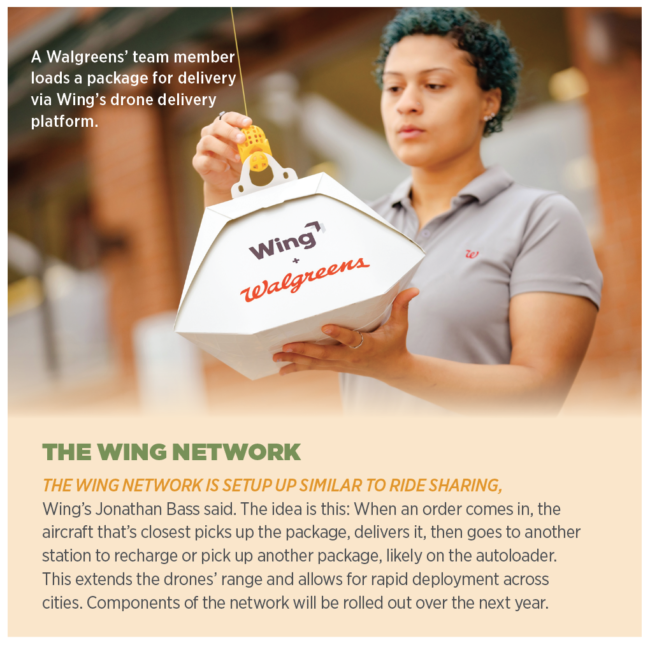

As industry works to overcome regulatory hurdles, progress has been made in the technology and where delivery drones can fly. Wing, for example, has moved from flying in rural environments to suburban areas and to metro areas in Australia, said Jonathan Bass, head of marketing and communications. The company has honed its ability to deliver packages directly to homes in densely populated areas, which is key to scaling.

Still, many drone delivery programs targeting the U.S. are setting up shop in the same areas, limiting impact. Dallas-Fort Worth, for example, is popular, Jones said, because aircraft are required to have transponders in the area’s Class B airspace.

“That relieves the technological burden this whole industry is dealing with,” Jones said. “To make these flights efficient, you need to fly BVLOS, and under FAA regulations, the drone is on the bottom of the hierarchy list of who has to give way. Drones need some technological assistance to see other aircraft. One of the easiest ways is in an airspace where all crewed aircraft have transponders. Without that we have to stand up other technology, which might be costly radars or cameras that are still going through testing and evaluation.”

Delivery company Flytrex set up stations in North Carolina and Dallas-Fort Worth for local on-demand drone delivery. Partner Causey Aviation Unmanned (CAU) received a Standard Part 135 Air Carrier Certification from the FAA for long-range on-demand commercial drone deliveries in the United States. Flytrex aims to replace services like Door Dash and Uber Eats, CEO and cofounder Yariv Bash said, by bringing the cost of deliveries down to less than $1. Customers receive food faster and restaurants won’t have to pay the high fees other delivery services charge.

“You’re certifying a commercial airplane, which is an expensive process, but then you’re going to use that commercial airplane for backyard deliveries for a few bucks a flight,” he said. “That’s a price point I’d say was impossible until now. But that’s the secret sauce. It’s not just engineering, it’s engineering with regulatory, operational and financial constraints.”

The drone technology Flytrex leverages is optimized for short range delivery with payloads of about 6.5 pounds, Bash said. They’ve developed an end-to-end stack that “enables the drones to perform in a very autonomous and affordable way.” The cloud-based software mitigates every function, tracking the number of flights performed and automatically marking drones for maintenance when it’s time.

Once an order comes in, a runner picks it up from the restaurant and brings it to the station a few hundred yards away, he said. The operator loads the food, the drone autonomously flies to the customer’s backyard and lowers it via hook and tether.

Wing’s lightweight platform is also customized for delivery, Bass said. The team can set up a delivery service with multiple aircraft in the corner of a parking lot, with most deliveries complete in 15 minutes or less. The drone hovers for delivery and uses a hook to lower packages to the ground. Wing went through about 20 iterations to design a pill that wouldn’t flop around as it retracts for safe and stable deliveries.

Wingcopter plans to test grocery delivery to remote German villages in the next few months, Plümmer said. The company will use electric cargo bikes to deliver the groceries from the landing sites just outside the villages to the customers’ homes.

The drone making the deliveries, the Wingcopter 198, is a hybrid fixed-wing eVTOL drone that can take off and land almost anywhere just like a traditional multicopter, while flying long distances fast and efficiently like an airplane. Payloads transported in an aerodynamic delivery box can be lowered through a winch. The company is working on a triple-drop mechanism that makes it possible to carry three packages on the same flight and deliver them to different locations.

Wing also has developed an autoloader that’s expected to be rolled out later this year. The drone can pick up packages placed on the autoloader, automating the process.

Zipline recently introduced a home delivery platform, the P2, Wryobek said, and uses a droid to complete deliveries, a critical component.

“When the Zip arrives at its destination, it hovers safely and quietly at that altitude, while its fully autonomous delivery droid maneuvers down a tether, steers to the correct location, and gently drops off its package to areas as small as a patio table or the front steps of a home,” he said. “This is all made possible through major innovations in aircraft and propeller design.”

OTHER APPLICATIONS

While residential delivery is the ultimate goal, “drone delivery is making real inroads in many business sectors,” Zhang said.

“In the short-term, under the current regulatory environment, I see delivery drones finding new use cases where their unique ability to complete deliveries faster than traditional ground transportation, and at a massive savings, has real appeal to many business sectors,” he said. “Offshore logistics is a perfect example. A delivery drone can transport spare parts or tools much faster and cheaper than dispatching a whole boat to steam out to a wind farm.”

Construction sites, mines and refineries can and are using drones to quickly deliver parts and tools. These types of missions are easier to fly from a regulatory perspective, Magirias said, but the key is finding the use cases that truly add value.

As an example of an out-of-the-box application, Zipline is delivering animal health products such as vaccines, swine semen and other substances that are difficult to ship to veterinarians, Wryobek said. The smooth, temperature-controlled drone flights are better for these products than the shaky rides they might experience on the back of a truck.

“As we work with our partners we’re finding more and more untapped use cases for our service,” Wryobek said. “There are so many stale and inefficient processes that we can completely remake thanks to this entirely new paradigm of transit. There’s no way we’ve thought of every use case yet and we’re excited to see how different sectors embrace this opportunity.”

THE TECHNOLOGY

To scale parcel delivery, packages must be delivered BVLOS, and that requires an aircraft that’s safe enough to operate over people and moving vehicles, Jones said. That goes back to obtaining type certification.

These drones also need “tremendous redundancy,” similar to commercial aircraft, for BVLOS flights, Wimberley said. They must have durable components and offer reliability, even in harsh weather conditions, under load and after the strain of making multiple flights day after day.

Radio links, 4G modules, computer vision systems, parachute systems and other delivery mechanisms, control stations, reliable communication systems and tracking software are among other requirements.

Delivery drones must be able to see and avoid other aircraft as they travel, Jones said. An unmanned traffic management (UTM) is necessary to segregate drones, and that requires detect and avoid on the aircraft or a ground-based system.

Wing already operates under a UTM structure, Jones said, leveraging their own software program. Other package delivery companies are doing the same or looking to partners to provide the structure. The goal is to develop industry governance, and to have agreement on the best UTM moving forward.

POSITIONING AND MAPPING

As delivery operations become more challenging, precise positioning and heading are even more crucial. To meet that need, Trimble recently introduced the PX-1 RTX, allowing drone integration companies to add precise positioning capabilities for takeoff, navigation and landing, Qiao said. The solution, designed specifically for delivery applications, leverages Trimble’s CenterPoint RTX corrections and GNSS-inertial hardware to provide real-time, centimeter-level positioning and accurate inertial derived true heading measurements.

“The receiver is loaded with the latest technology to improve signal quality and protect against jamming and spoofing,” Qiao said. “It can receive high-integrity over the air corrections delivered straight to the receiver, so it achieves centimeter level accuracy without the need for an RTX base station. It also has Applanix IN-Fusion+, which takes measurements from GNSS, IMU and RTX to output the best position and orientation for the drone so you end up with precise, consistent positioning.”

Early adopters are testing the system now, Qiao said.

DDC uses cellular or satellite coms for positioning, Magirias said, and everything is operated through flight software. The way points are preprogrammed, with the drones flying the same route every time. Mapping is also completed through the software.

A2Z’s newer drones rely on GPS RTK, Zhang said, for delivery site accuracy.

“We map the delivery route beforehand, and make sure there are no power lines on the delivery waypoint,” he said. “With centimeter-level accuracy RTK, we are able to safely deliver at the same spot every time.”

Wing uses GPS along with a vision-based backup, Jones said. Once a customer signs up for the service, a survey is completed to determine the best place for deliveries. If there’s an obstacle in the delivery zone when the drone arrives, the nudge system detects it and the drone will place the package nearby.

The mapping system is robust, Bass said. When a customer places an order, Wing’s systems generate a route that is deconflicted from obstacles, terrain, restricted airspace, areas of known traffic density, and other Wing delivery aircraft. The aircraft use a variety of map and terrain data and sensors, including GNSS, that create an integrated, redundant navigation solution designed for safe operations at scale in varied environments.

Zipline uses its own custom positioning system, Wryobek said, with fully redundant GNSS, INS and weather sensors layered in with local corrections that provide real-time centimeter level accuracy. Offline route planning optimizes nominal routes.

“A major challenge we face as an autonomous service is that we must execute all the logic it takes to navigate safely onboard our aircraft,” he said. “That means telling the difference between good error data and bad error data, detecting and avoiding hazards without losing flight margins, and many other subtleties. Getting it right and executing on a very small and light drone takes a phenomenal amount of testing.”

WHERE WE’RE HEADED

The technology is already in place for residential parcel delivery, Zhang said, it’s a matter of waiting for the regulations to catch up. Of course, manufacturers must prove they can fly safely and reliably, to gain both regulatory approval and public acceptance, Plümmer said. To ensure safe BVLOS deliveries, manned and unmanned industries will need to work together to develop a UTM.

Medical deliveries will continue to flourish, and more companies in industries like oil and gas will realize the benefit of on-site drone deliveries. In the next 10 years, Plümmer predicts there will be drone delivery networks that span entire countries, with these systems a common site in our skies.

“Drones are going to be a very significant part of a multi-modal delivery environment,” Bass said. “They’re well suited to deliver small packages quickly, while the ground delivery system works well for larger packages. It won’t replace ground delivery but will augment it for faster delivery of small packages.”

And as the industry works to get more aircraft type certified and to develop the UTM system required for drones to safely operate in the National Airspace System, it’s opening the door for even bigger opportunities.

“What we’re working on now will help us get to advanced air mobility,” Jones said. “It’s a natural progression. There’s not a whole lot of difference in what’s required for small package delivery and cargo delivery when it comes to the safety around avoiding other aircraft. With a focus on AAM, we’ll see things start to pick up.”