American unmanned aircraft Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) has reached a plateau. The U.S. military knows how to operate ISR drones from thousands of miles away from combat, distribute sensor data to hundreds of intelligence analysts in seconds and provide analyzed intelligence directly to forces in combat within minutes. Seventy combat air patrols of General Atomics MQ-9 Reaper and MQ-1C Grey Eagle stand watch around the world 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Sophisticated U.S. drone sensors can recognize targets from miles away. Their electronic surveillance gear can characterize any signal they detect and send warnings within seconds. America can do little to refine its unmanned ISR armada—as long as it continues to operate it largely unopposed.

The Department of Defense—particularly the U.S. Air Force (USAF)—has known for years that its unmanned ISR enterprise is a “permissive environment” only, in which it wouldn’t last long against determined enemy air defenses. The USAF has an extensive program to develop unmanned ISR that avoid enemy air defenses, and is taking care to build an open architecture system. This includes universal control interfaces that define data needed to execute drone missions, open mission system architectures that specify how software and hardware operate together, and an autonomy core system that provides a common “nervous system” that will allow specific artificial intelligence “brains” to make drones genuinely autonomous.

USAF common standards inform the industry on how to make autonomous drones, but the Air Force is still trying to figure out what kinds they should manufacture. Small numbers of very expensive but very stealthy drones? Smaller numbers of less costly conventional drones like the MQ-9? Massive numbers of inexpensive attritable drones that may—or may not—come back from each mission? Perhaps we can glean something from the unfortunate situation overseas.

INVASION TAKEAWAYS

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine provides a unique chance to see how drones can work in contested air warfare. Thus far in the war, Russia’s air defenses are still effective, as are Ukraine’s. The deadliest air defense weapons for both sides are the long-range surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) like the S-300 (NATO SA-10), S-400 (NATO SA-21) and Buk (NATO SA-11), which can hit targets between 25 and 250 miles away. These long-range SAMs denied both sides medium and high-altitude airspace, preventing combatants from flying reconnaissance aircraft over enemy territory at will. Ukraine mitigates this with shared Western intelligence. Russia is blind over most of Ukraine.

Low-flying crewed reconnaissance aircraft and scout helicopters typically allow combatants to monitor enemy forces near the front lines, even if long-range reconnaissance aircraft can’t get through. Shoulder-launched and mobile missiles are decimating these aircraft because they can’t fly above the missiles effective ranges due to the deadly long-range SAMs.

What drone strategy has been working so far? Large numbers of hobbyists flying consumer drones—the Ukrainian version of swarming attritable drones. Aerorozvidka, an entrepreneurial organization of Ukrainian IT experts and drone enthusiasts, has been operating consumer drones to significant effect from the beginning of the war. Its drones rarely last more than a few days in combat, but at $1,000 per replacement and with “dronations” pouring in from around the world, Aerorozvidka has been a constant presence over the battlefield. Ukrainian remote pilots have used a variety of mainly commercial communication methods—including Elon Musk’s Starlink satellite constellation—to relay targeting data to strikers, proving that even commercial networks can be effective in a drone war.

Smaller numbers of conventional drones also appear effective, although it is difficult to tell due to wartime security. Before the war, Ukraine bought several dozen Turkish Bayraktar TB2, which are roughly equivalent to the General Atomics ASI MQ-1 Predator. By flying below long-range SAM coverage and limiting their time over enemy territory, Ukrainian TB2s have apparently avoided getting wiped out so far by Russian shoulder-launched or mobile SAMs. They are not flying continually over Russian forces like USAF MQ-9s fly over targets in Afghanistan, but the TB2s continue to make an impact.

The strategy that is not working well is flying a small number of attritable drones and a complete lack of conventional drones like the TB2 or MQ-9. Russia has been flying a relatively small number of Orlan hand-launched drones that can cover a few miles behind Ukrainian lines. The Russians cannot keep up with attrition from Ukrainian drone defenses and, to date, have not flown large numbers of commercial drones like the entrepreneurial Ukrainians. Inexplicably, the Russians never developed a drone like the MQ-9. This, again, gives a lopsided ISR advantage to Ukraine.

The results of both drone strategies are becoming apparent. Ukraine has excellent knowledge of Russian forces far behind their lines thanks to Western intelligence and even better knowledge of Russian front lines from its swarms of cheap commercial drones. On the other side, Russia is struggling to track Ukrainian forces both deep behind their lines and on the line. But what good is accurate ISR if you don’t have the capacity to strike?

Here Russian and Ukrainian advantages appear to be reversed. Neither side can effectively employ its air forces, and Russian conventional artillery outnumbers Ukrainian artillery ten-to-one. Russia has long-range cruise missiles and accurate ballistic missiles. Ukraine has a handful of extremely accurate Western missile and artillery systems it has used to significant effect, but it may not be enough. The war drones on.

POST-UKRAINE DEVELOPMENT

Does any of this help guide the USAF with drone strategy? Clearly, long-range SAMs are effective, as the USAF feared. In conflicts without long-range SAMs, American drones avoid shoulder-launched and mobile missiles by flying higher than these missiles can engage. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine confirms the basic tenet of USAF future drone strategy—that “permissive environment” drone tactics won’t work against opponents with advanced airspace weapons.

The war is providing evidence that an attritable drone strategy works, but the USAF will need attritable drones that are much larger, more capable and much more expensive than Ukraine’s commercial drones. Drones that can only fly a few miles into enemy territory are useless to the USAF; the Army handles the close-in fight, not the Air Force. Twitter is full of Ukrainian drone attacks using rifle grenades and other small explosives. These are effective when dropped down tank hatches and against Russian troops in the open but are nowhere near the size of munitions wanted by the USAF.

A long-range, high-capacity drone that is cheap enough to lose yet safe enough to fly repeatedly is a tall order, but it appears industry is answering the call. General Atomics ASI is working on two attritable drones under the Air Launched Effects (ALE) program that will produce drones launched from other drones or helicopters. One is the Eaglet, an expendable drone designed for single use. The other is the Sparrowhawk, which is much larger and designed for multiple flights. It cleverly uses an MQ-9 “drone mothership” to launch, recover and even refuel. Such attritable drones will allow the USAF to monitor both the front lines and deep into enemy territory. Unfortunately, neither has the payload to carry the weapons needed to destroy the targets they find—a shortfall similar to Ukrainian attritable drones.

Unlike Ukraine, the USAF has a wide range of existing long-range precision weapons available to strike targets found by an attritable drone fleet. They are making some of these existing weapons more autonomous and collaborative to allow them to work together to survive enemy defenses and destroy targets found by ISR drones. The USAF has already advanced its autonomous collaborative weapon program from the 50-mile ranged Small Diameter Bomb to the 600-mile ranged Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile in Project Golden Horde. Conventional drones, like the MQ-9, can become “bomb trucks” operating outside enemy defenses for attritable “drone wingmen” operating within enemy SAM range to find targets.

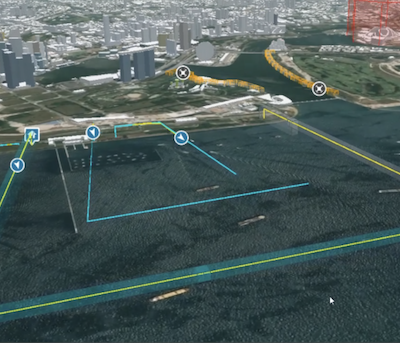

Ukraine is also proving conventional drones that, flown carefully, can survive enemy air defenses. No doubt, this is spurring the USAF to change its view that conventional drones are only valuable for uncontested airspace. The USAF introduced MQ-9 and RQ-4 remote aircrew to its elite Weapons School several years ago, but now, instead of studying how to strike counter-terror targets, top USAF aircrew are figuring out how conventional drones can survive a contested fight. The USAF disclosed that MQ-9s flying outside (simulated) SAM range with communications relay pods participated successfully in two Pacific exercises over the last year.

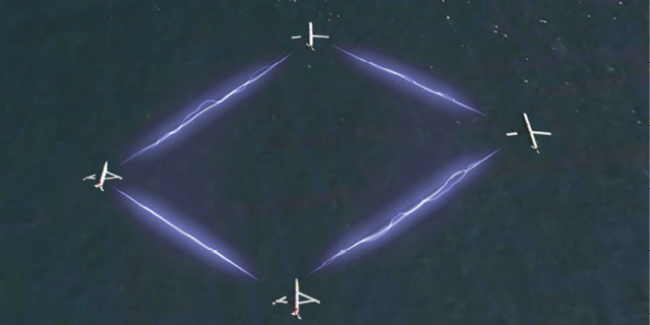

The war in Ukraine has no lessons for employing low observable drones because the Russians haven’t developed any and the U.S. has not provided them to Ukraine. Yet. However, the lethality of air defenses in Ukraine points to how critical it may be to employ stealth drones teamed with stealth crewed aircraft to directly attack long-range SAMs that have grounded both air forces over Ukraine. If it works, the USAF’s Loyal Wingman program—autonomous, collaborative drones that can fly within enemy air defenses under the control of crewed stealth aircraft—may be the key to taking down long-range SAMs, allowing the rest of its fleet to operate with impunity over enemy territory in the future.

That is a big “if it works,” and something we must wait for the next war for verification. Unless, of course, the U.S. provides Ukraine stealth drones after Putin’s next escalation.