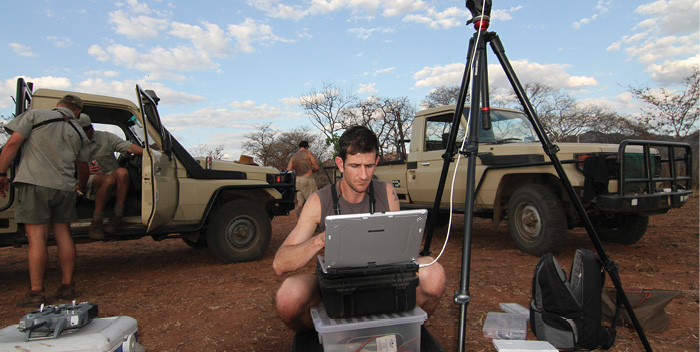

Damien Mander, founder of the International Anti-Poaching Foundation, prepares to launch a drone. International Anti-Poaching Foundation

Night at Kruger National Park. A group of men scale the park fence under cover of darkness and make their way to a nearby watering hole.

Rhinos come here at night to drink, but tonight they are in danger. The men carry tranquilizer darts and chainsaws; they’re seeking rhino horn, a substance that—despite being made of the same stuff as our hair and fingernails—is more valuable on the black market than gold, diamonds or cocaine.

A rhino approaches from the south—but at the same time the men hear a drone approaching from the west. One of the men looks down and sees a red laser targeting dot hovering directly over his chest. The men drop their gear and flee and the rhino lives another day.

This scenario is how many wildlife advocates and UAS manufacturers envision the near future of counter poaching. Despite international efforts to ban the sale of products like ivory, rhino horn, and tiger bone, hundreds of animals are killed a year for these “items,” valued in traditional Asian medicine and as status symbols. Many believe drones are the answer.

While there are no statistics showing how many national parks and wildlife reserves are using drones in their conservation efforts, it’s safe to say the devices are a current or future solution for almost any national park troubled by poaching. Unmanned aircraft can help a park’s rangers extend their influence, letting them oversee a much larger area than they could by car or on foot. And someday soon, drones might even play more tactical roles, chasing down and tagging or even incapacitating poachers.

Drones as Surveillance Tools

The most common usage for drones in counter poaching is as an extension of a ranger’s eyes and ears. Kruger National Park, in northeastern South Africa, is home to about 8,000 white rhinos, the largest concentration of the large animals on the planet. It’s also the size of New Jersey, and has a porous, 275-mile border with Mozambique, where poaching is treated as a misdemeanor. So it’s nearly impossible to monitor the entire park, no matter how many rangers are out scouting the terrain.

Drones can observe animals to learn where they are or patrol border fences for intruders. Many parks are already using a handful of drones; Kruger, for example, is using a borrowed Seeker II, a fixed-wing UAS made by South African firm Denel Dynamics. It has a 10-hour range and a 40kg payload and works at night. A drone can spot a poacher 10 miles away and alert a ranger, who can then approach and apprehend them.

“Drones give you that bird’s-eye view of a much larger area,” said Princess Aliyah Pandolfi, a descendant of Kashmiri royalty and the CEO and executive director of the Kashmir World Foundation, which is hosting an international competition to design a low-cost drone for use in the park.

Pandolfi’s Wildlife Conservation UAV Challenge saw 140 entrants vying to make a successful open-source aircraft that can detect and locate poachers with on-board image processing for a materials cost of less than $3,000. Judges have whittled the 140 entrants down to about 50; a total of 20 contestants will be selected to travel to South Africa for the “Counter Poaching Games,” with actors playing poachers to put the drones to the test in a lifelike scenario.

Those games have been grounded for now, since South Africa’s aviation authority issued new rules affecting commercial and non-profit drone flights and flights over public land. But good news: the Kashmir World Foundation is in talks with a wealthy businessman whose private game reserve borders Kruger. It should be possible to hold the challenge on the privately owned land, so Pandolfi is hopeful she and the owner can come to an agreement soon.

Rhino horn is more valuable than diamonds, gold, or cocaine. International Anti-Poaching Foundation

So far much of the interest in drones for counter poaching has been focused on Kruger and other South African parks, partly because—until the new regulations—South Africa was one of the few countries where it was legal and feasible to fly a drone. But drones are also being put to work fighting poachers elsewhere. In Nepal, rhino poaching has been reduced to nearly zero. This is due in no small part to the country’s zero-tolerance attitude toward wildlife crime; its laws allow forest officers and wildlife wardens to impose prison sentences of up to 15 years. But some of the credit can also go to the World Wildlife Fund and Conservation Drones, a nonprofit that provides tools and technology to conservation researchers and the anti-poaching community. Conservation Drones provided the top management of Nepal’s Chitwan National Park with training to fly 10 drones to spot poachers. “People [now] know they might be seen from the sky if they enter a national park,” said Serge Wich, cofounder of Conservation Drones and a professor in primate biology at Liverpool John Moores University. “That might lead people to see there’s a higher risk of being caught.”

Even as literal eyes in the sky, drones can’t solve every problem.

First, onboard image processing is a challenge that many manufacturers are still solving. Without it, a ranger has to sit and watch the live video feed from a patrol drone for hours. “You’ll pretty much go brain dead if you’re sitting there all day long,” Pandolfi said, “and then you take a two-minute break and you might have lost the most valuable information” of the day.

A company called Dutch UAS, a for-profit spinoff of a Dutch nonprofit called Red de Neushoorn (Save the Rhino), may have solved this problem; business director Pieter Oranje said Dutch UAS’s fixed-wing platform can be controlled from a tablet and will fly on autopilot until it detects an object. This is computationally expensive, and therefore financially expensive, which is why Dutch UAS hopes it can translate its experience building software for cash-poor national parks and reserves into making some money from commercial uses. (Oranje said the same drone and software could be used to monitor crops and livestock remotely.)

Another issue is these parks are enormous. “You could fly a drone for weeks, if not months, in Kruger National Park at night and probably not see anything,” said Tom Snitch, a visiting professor at the University of Maryland Institute for Advanced Computer Studies (UMIACS). And even if drones could effectively survey a park as big as Kruger, rangers can’t necessarily get to the scene of the crime soon enough. “How fast can your rangers move at night?” Snitch asks.

Pandolfi suggests that unmanned aircraft could be used in tandem with manned aircraft (and in fact Kruger uses two donated helicopters to move rangers quickly), but it’s still clear that the scope of the problem is huge. That’s where Snitch’s research comes in. In partnership with a South African drone developer, UDS, Snitch uses mathematical models to help rangers predict where to deploy drones and rangers.

Snitch pulled together data on rhino killings in two parks, looking at factors like the weather that day, whether the moon was out, “how far was the animal killed from a watering hole? How far from a road? How far from a village? What day of the week was it? There’s one particular reserve [where] every single rhino had been killed within 160 meters of a road…Poachers were driving to the park and looking to see if there were rhinos near the fence. Then they drive back at night, climb the fence, and kill the rhino.”

But when he spoke to officers at the park, saying data showed rhinos were killed near the roads, the officers said they were spreading their rangers out across the entire park.

“You talk to a warden, and he goes, ‘I gotta protect 150 square miles,’” Snitch said.

In a perfect world, the decision for where to fly and where to deploy rangers would be out of human hands, made by a computer. “The mathematics have said that the most likely 1 kilometer of fence where the poachers cross is right here,” said Snitch. “So you put the…drone nearby. And when the computer said there’s a 90 percent chance of poaching, you put [rangers] out very close to that threat zone. And the…drone says, ‘are there any rhinos nearby?’ And then you make sure the rangers are between the fence and the rhinos. If you were up there and you surveyed the area and there were no rhinos within 20 kilometers, you wouldn’t [have to] send your troops out that night.” If there are rhino sightings, though, the rangers can sit in their Jeep with a laptop or tablet and watch live video. “When these guys cross the fence, they light up like Christmas trees.” The rangers don’t have to stare at the screen all night, just during the peak times predicted by the model.

Before South Africa banned drone flights, the park Snitch was working in, in partnership with UDS, reduced poaching to zero.

“The poachers realized that rather than operate with impunity… suddenly there was a new sheriff in town and a technology that could see them at night. And I think it was very, very disruptive,” he said.

Even better: The poachers haven’t moved their activities to a new area.

“These are local people who know the region. They know the land, they know where the animals are going to be,” Snitch said. “How would you move those guys 40 miles to the north?” The locals couldn’t translate their knowledge of where animals could be found to a new area—and just as crucially, there were often established poachers in other areas who would “not take kindly to interlopers.”

Pandolfi agrees that once poachers are removed from an area, they’ll likely take the path of least resistance. “They’ll probably find another location, another animal, or they’ll find something else to do.”

Rapid Composites’ Bullray UAS. Rapid Composites

Drones as Weaponry

There are some who say knowing where poachers are (or where they will be) is not enough.

Pandolfi, for one, suggests that counter poaching drones should scare criminals off.

“Something as simple as a red dot on your chest in the middle of the night, that would really scare these poachers,” he said. “They wouldn’t want to risk going after these animals, because you don’t know what [the drone] is capable of.”

Eventually, though, poachers will probably figure out that the dot is just a harmless dot. That’s where Rapid Composites’ Bullray drone comes in.

The rugged, waterproof copter (tri-, quad, penta- or hexa-) is the first to use a Picatinny rail system, a modular bracket system used with many weapons. So any gun or nonlethal weaponry that can be mounted on a handheld weapon can be mounted on Bullray. Alan Taylor, Rapid Composites’ president, said the combination of the Bullray and a non-lethal incapacitating launcher called the FN-303 could be a powerful weapon against poaching.

“One round incapacitates,” Taylor said. “It is a potential game changer in law enforcement and military…this launcher system, we believe, has a lot of potential to be used for anti-poaching campaigns.”

A team from Aurora Flight Sciences tests the Skate drone in South Africa. International Anti-Poaching Foundation

The system has already been used in a handheld configuration by law enforcement around the world, though admittedly not without incident. In 2004 in Boston, a crowd control officer fired an FN 303 round while trying to break up a crowd rioting to celebrate a Red Sox victory. It struck a college student in the eye, and she died before medical help arrived. The officer who fired the weapon had said he had been aiming at a rioter throwing bottles and didn’t know a bystander had been hit, but a few years later, the Boston Police department destroyed their remaining FN 303s.

Taylor concedes that the tool is very powerful and must be used responsibly. “We have to make sure that the range and the parallax for targeting is absolute,” he said, explaining that Rapid Composites is about half a year from market as it fine-tunes its targeting algorithms. “If we bill it as less than lethal it has to be less than lethal.”

Members of the Dutch UAS team with their aircraft. Dutch UAS

The Limitations of Drones in Anti-Poaching Campaigns

“The biggest mistake people think about drones in Africa,” UMIACS’ Tom Snitch said, “is that it’s a silver bullet.” In reality, drones are one piece of a very complicated puzzle.

For one thing, the cost of many drones puts them out of reach of cash-strapped wildlife sanctuaries.

“Poaching is such a big problem, you want to spend every Euro you have on effective antipoaching methods, and you don’t want to budget money for R&D,” Dutch UAS’s Oranje said.

Snitch doesn’t buy that argument. Drones have more uses than just nighttime surveillance, and could actually save parks money, he said.

“These parks are all fenced. [Say they have] 80 kilometers of fence that has to be monitored every day. Two guys gotta get in the truck and drive 80 kilometers and look to make sure there are no holes dug under the fence. It takes them 8 hours.

Simon Bert of the International Anti-Poaching Foundation. The Foundation is looking for professional support including skilled people to help introduce and implement technical solutions in Africa. International Anti-Poaching Foundation

“Instead of you driving, let’s fly a drone 30 feet above the ground parallel to the fence and have the drone videotape the entire fence. This drone does it in 90 minutes. You saved two guys, eight hours, and 51 liters of fuel. [In five or six months,] you could buy a drone with the gas you save.”

Training is also an issue. While you can get a ranger up to speed and flying a drone in a day or two, there’s a cost associated with that, and someone needs to know how to reattach a camera or propeller if the drone doesn’t quite stick the landing. And in those countries where governments ban drone flights, the entire idea of using them in anti-poaching is grounded.

Finalizing U.S. regulations may go a long way toward opening up other countries to unmanned aircraft.

“When I talk to African governments, they say, ‘Well, what are the FAA’s rules on drone flying in the U.S?’” Snitch said. “’So you can’t take your drone and fly it in the U.S.—so you want to come into my country?’”

Ultimately, all the drones in the world can’t stop poaching if corruption continues to be an issue. “A ranger’s salary is like 6,000 rand ($433 USD),” Pandolfi said. “If somebody’s going to give you 20,000 rand to look the other way, it’s really tempting.” Corruption at higher levels funnels money out of parks and lines officials’ pockets to ensure the “valuable” rhino horn continues to leave the country and travel to Asia. And as long as rhino horn continues to be prized for its purported medicinal properties, poaching is still an attractive option for those living in poverty and seeing themselves with few other choices.

But stopping the demand is not going to be easy. And in the meantime, equipping park rangers and officers with drones can help.

“In the areas under the greatest threat,” Snitch said, “I can absolutely guarantee you if you let us come in we can stop poaching in its tracks. I guarantee 1000 percent.”