The flight path toward normalizing and integrating UAS into the National Airspace System begins to clear.

The long-awaited Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC) final report dropped on March 20. The almost- 400-page document comes nine months after the FAA chartered the ARC, and three months beyond its originally projected deadline. Here we break down the report into key elements, with analysis and predictions for the way ahead.

ESTABLISHING A RISK FRAMEWORK

The FAA chartered the ARC last June, “to make recommendations to the FAA for performance-based regulatory requirements to normalize safe, scalable, economically viable and environmentally advantageous UAS BVLOS operations that are not under positive air traffic control.” Emphasized items specifically included UAS BVLOS support to long-line linear infrastructure inspections, industrial aerial data gathering, small package delivery and precision agriculture operations, including crop spraying.

A diverse team of experts gathered to tackle this effort. Representatives came from academia and standards bodies; critical infrastructure owners and operators; infrastructure security; privacy groups; state, local, tribal, territorial interests—including environment and equity considerations; technology and network infrastructure interests; traditional aviation associations; and UAS associations.

These teams spent thousands of hours in meetings, divided into various groups and subgroups and working in two phases. Phase 1 focused on understanding the landscape and developing a pathway forward. It explored topics such as “Safety,” “Environment and Community,” “Market Drivers” and “Regulatory Challenges.”

Phase 2 focused on establishing a risk framework, building on Phase 1 inputs. During this Phase, the ARC made recommendations for UA with a resultant kinetic energy of up to no more than 800,000 foot-pounds (representative of a Light Sport Aircraft, or LSA) to conduct “fly to rule” BVLOS operations…without waivers.

DEFINING RISK LEVELS

The ARC focused on safety and societal benefits as its guiding principles. While safety may be an obvious focal point for a potential aviation rule, societal benefit got a lot of play. Why? To justify a risk-based approach that deviates from the typical “regulate to prevent the worst case scenario” mindset of crewed aviation.

As Jon Damush, CEO of Iris Automation and ARC member, explained: “This is probably the first time in aviation where risk has become two-dimensional in terms of probability and consequence. With crewed aviation, the consequence of an accident is dire because souls are on board. With UAS, this is not the case. Until now, we’ve never been able to consider the question: ‘What is an acceptable level of risk?’”

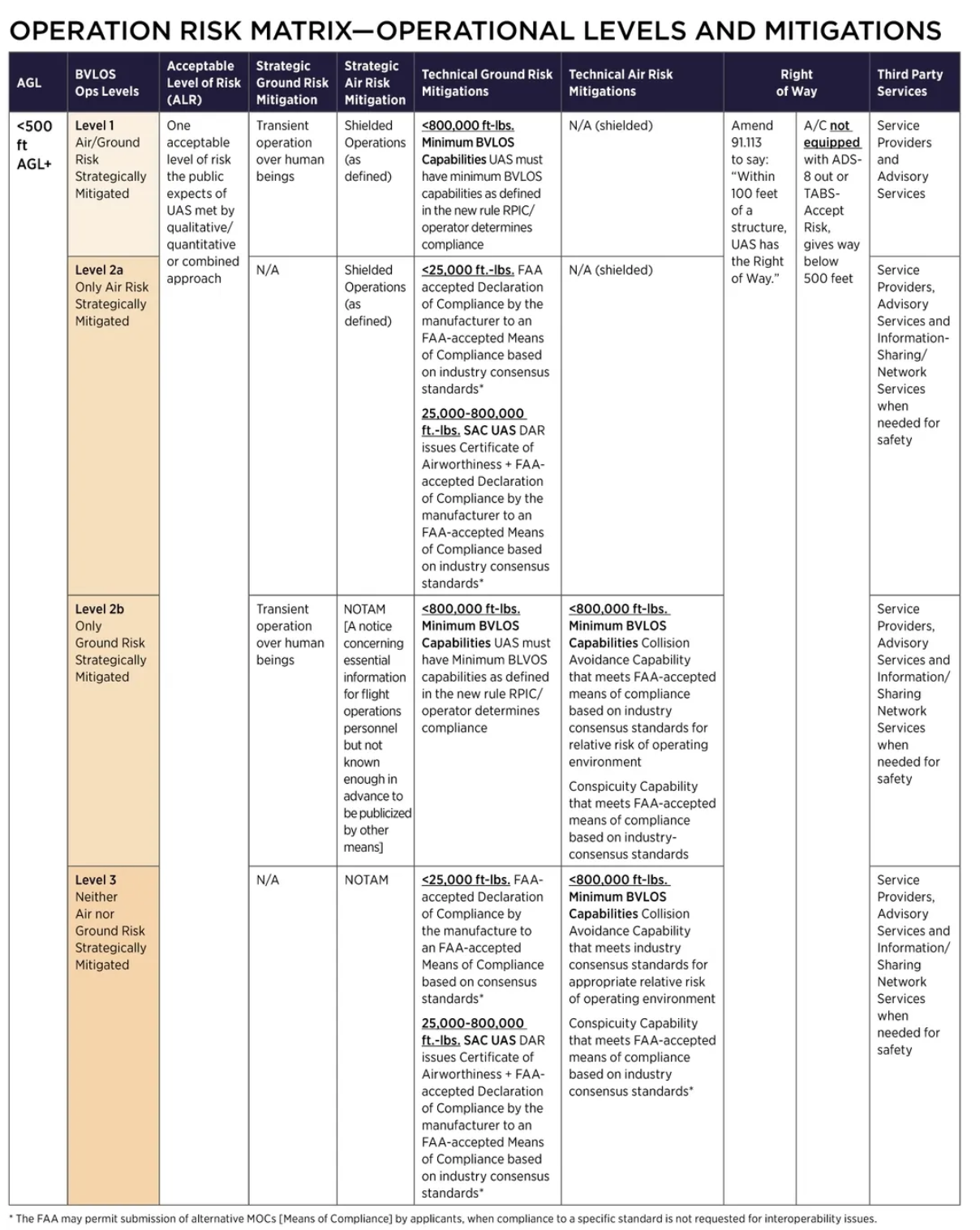

The ARC answered this question by recommending a consistent acceptable level of risk (ALR) across all types of UAS operations, encapsulated in a regulatory framework supported by an Operation Risk Matrix and an Automation Matrix. These both use qualitative and quantitative approaches to assess air and ground risks to enhance compliance and reduce risks to an acceptable level.

The Operation Risk Matrix defines risk levels based on a number of factors, including strategic and technical mitigation and the UAS’ kinetic energy, as applied to an operation. The Risk Levels are 1, 2A/2B and 3 (the highest level). Strategic mitigations reduce risk prior to flight. Technical mitigations reduce risk in flight.

The Automation Risk Matrix describes the acceptable ranges of autonomous UAS operations and prescribes the operator qualifications necessary to conduct them:

• AFR Level 1—A manual system (“human in the loop”), where direct monitoring and human interface are necessary and intended for the vast majority of flight.

• AFR Level 2—A system with increased automation (“human on the loop”), in which human remote pilots are responsible for the flight of assigned aircraft, and are expected to directly monitor and maintain situational awareness for the flight(s) under their control.

• AFR Level 3—Extensive automation, similar to existing on-demand delivery operations (“human over the loop”); may not require human intervention to operate successfully, but may accommodate human supervision and intervention; used to support substantially one-to-many operations.

• AFR Level 4—A state of ultimate automation (“human out of the loop”), handled completely by the automation, with no human intervention.

An Automation/Automated Flight Rules Risk Matrix (page 43-44 of the report) describes the various requirements for human roles and qualifications, and any limits to operations. Equipage requirements are listed as TBD.

This approach provides operator flexibility to meet those ALRs through qualitative or quantitative methods, or a hybrid approach. It footstomps rules based on the risks of operations, based on UA capability, size, weight, performance and characteristics of the operating environment, not the purpose of the operation.

“It is good to see the move toward a risk-based approach and the aspiration to scale to routine BVLOS flights, rather than Proof of Concept,” said Julie Garland, CEO of Ireland-based Avtrain. “We have proven the concept over and over again. Now it is time for scale.” Garland was pivotal to the creation of the Future Mobility Campus Ireland (FMCI), Skyports and Shannon Group consortium, called FMCI Air. FMCI established Ireland’s first drone air taxi service and routine BVLOS drone operations.

CHANGING FLIGHT RULES

The need for BVLOS operational flexibility led to recommended modifications to the right of way rules and conspicuity requirements for UAS. According to the report, conspicuity—technology that can help pilots, UA users and air traffic services be more aware of what is operating in surrounding airspace—could include strobe or other lighting features. These requirements could be established by Means of Compliance (MOC), through a standards development organization (SDO).

The biggest change would be in the Right of Way rules. The ARC suggested modifying the See and Avoid & Well Clear requirements in Part 91.113 (b) to allow a range of sensing methodologies and to clarify adequate separation.

FAR § 91.113(b) would be amended as follows:

General. When weather conditions permit, regardless of whether an operation is conducted under instrument flight rules, visual flight rules, or automated flight rules, vigilance shall be maintained by each person operating an aircraft so as to detect and avoid other aircraft. When a rule of this section gives another aircraft the right-of-way, the pilot shall give way to that aircraft and may not pass over, under, or ahead of it unless able to maintain adequate separation.

In the suggested language above, the word “detect” has been substituted for the word “see’ “to allow the use of other sensing methods beyond human visual capabilities. “Well clear” has been removed and replaced with “adequate separation” to allow for different levels of separation for different situations, consistent with performance-based approaches. This also constitutes a paradigm shift from determining collision risk based on a volume of airspace to an approach based on acceptable level of collision risk appropriate for the airspace.

Perhaps even more controversially, the ARC recommended that in Low Altitude Shielded Areas (within 100 feet of a structure or critical infrastructure as defined in 42 U.S.C. § 5195c) and Low Altitude Non-Shielded Areas (below 400 feet, over crewed aircraft are not equipped with an ADS-B Out), the UA would have the right of way over crewed aircraft.

This topic consumed many hours of discussion, Darmush said. In his opinion, “Evert user of the airspace shares a collision avoidance responsibility. The means of achieving that are less clear at this point, but promising technologies continue emerging. The report recommends a change to right of way rules in lieu of pursuing technical solutions. This would be a good thing for UAS, but I have concerns about the impact to existing airspace users and crewed aircraft, specifically revolving around a human pilot’s ability to see and avoid a drone.” The U.S. still experiences on average four mid-air collisions a year, under the current rules, in cooperative airspace between cooperative aircraft using ADS-B, transponders, ATC contact and certified pilots with eyes-on.

On the other hand, Richard Podolski, director of UAV flight operations for Canadian-based Volatus Aerospace, believes this type of equitable access to airspace constitutes positive progress for the industry. “The BVLOS ARC is recommending amending 91.113 to allow UA right of way within 100 feet of a structure. Canadian regulations have been utilizing this approach and already have regulations from 2019 allowing (901.25) operation 100 feet above/200 feet beside a building or structure. Examples like this have opened up a significant amount of growth in Canadian industry and poses little or no risk to uncrewed aircraft…Flying 50 feet AGL [above ground level],” he continued, “clearly, the ground is far more dangerous to a crewed aircraft than a drone is at this height. The regulations need to reflect this.”

The thinking here is that UA-General Aviation (GA) encounters remain unlikely in shielded airspace because crewed aircraft typically do not work near obstacles. For the non-shielded change, existing regulations prohibit a significant portion of helicopters and non-agricultural GA aircraft from operating at low altitudes except for takeoff or landing.

Even so, the UA would still need to yield way in Non-Shielded Low Altitude Areas (i.e., below 400 feet AGL) to crewed aircraft equipped with ADS-B or Traffic Awareness Beacon Systems (TABS) broadcasting their position.

The ARC also recommended amending visual line of sight aircraft operations to include Extended Visual Line of Sight (EVLOS). This would allow operations where a remote pilot in charge (RPIC) does not see the UAS, but a trained crewmember has situational awareness of the airspace around the UAS. In Australia, Hover UAV already has this in place (see previous coverage at https://insideunmannedsystems.com/getting-nods-north-south-on-bvlos-inspections/).

The ARC made several other related regulatory amendment suggestions to support the proposed Operating and Right of Way Rules ranging from training crewed pilots on uncrewed flight operations to increase situational awareness, to preflight actions and amending minimum safe altitudes.

AIRCRAFT AND SYSTEMS

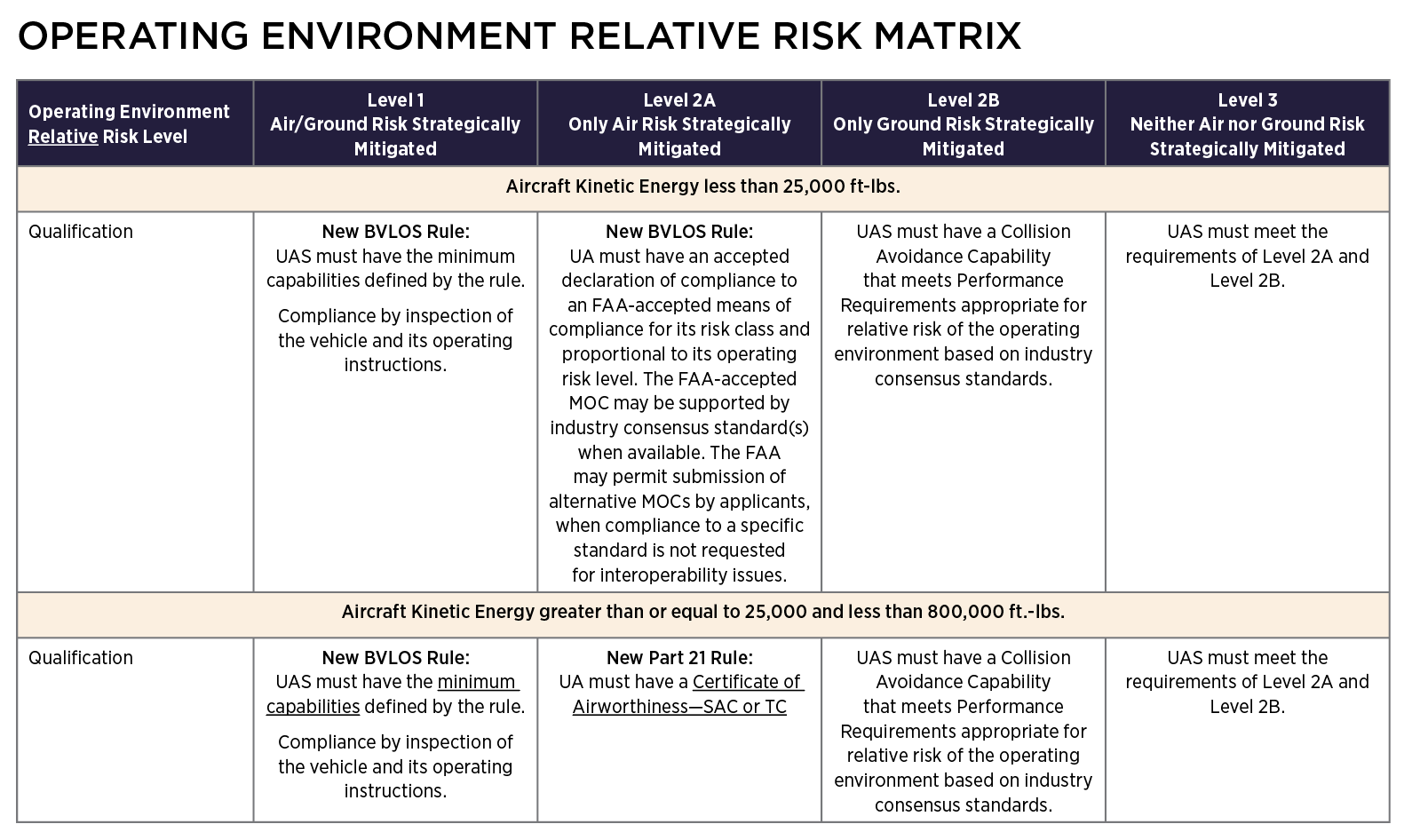

The key takeaway here is the ARC recommendation for a new BVLOS rule that would include a process for qualification of uncrewed aircraft and systems up to 800,000 foot-pounds of kinetic energy in accordance with the Operating Environment Relative Risk Matrix (see chart opposite page). The report suggests a complete overhaul of the qualification process based on risk and not a one-size-fits-all approach. “Qualification of UA should follow a risk continuum, aligned with the Risk Framework,” according to the report, “with the goal of meeting the acceptable level of risk [ALR]. Outside of traditional certification, the FAA should accept a statement or declaration of compliance to an FAA-accepted means of compliance.”

For small UAS, the report suggests, no airworthiness certificate should be necessary. A production certificate would not be required either, similar to the process used for LSA. Under this construct, the FAA could choose to review and accept certain applicant’s quality systems. However, applicants would not be required to gain acceptance or approval of the UA system or changes to the UA system.

Relatedly, the ARC recommends a slew of other UA updates around UA maintenance; software qualifications, noise certification, who must declare compliance and Repairperson Certification. It also calls for a new Special Airworthiness Certification for the UAS category, under Part 21 in higher relative-risk operating environments with UA from 25,000-800,000 foot-pounds. It also allows third-party test organizations to audit compliance similar to Europe.

OPERATOR QUALIFICATIONS

The ARC recommended a rule under the 14 CFR to govern UAS BVLOS Pilot and Operator certification requirements and operating rules. The overarching concept is that the FAA should align BVLOS qualification and certification requirements to the categories described in the Automation Matrix AFR Levels noted earlier in this piece. For AFR Level 1, a modified Part 107 could allow for limited BVLOS operations to be conducted under a Remote Pilot certificate with Small UAS rating (e.g. during EVLOS or “shielded” operations). For AFR Levels 2 through 4, BVLOS operations could be conducted under a Remote Pilot certificate with BVLOS rating per two new Operating Certificates for common carriage of property and other commercial operations.

The ARC also wants the FAA to create a new Designated Position of Remote Flight Operations Supervisor under the Remote Air Carrier certificate and the Remote Operating certificate for 1-to-many UAS BVLOS flights. This person would exercise operational control and ultimate responsibility for 1-to-many BVLOS flights conducted under their supervision, based on the AFR level.

Other topics covered included:

• Developing tailored medical qualifications for UAS pilots and other crew positions that consider greater accessibility and redundancy options available to UAS. tailored medical qualifications for UAS pilots and other crew members that reflect the reduced physical requirements for flying UA.

• Expressly authorizing RPICs of a UA to operate for compensation or hire.

• Allowing only appropriately vetted UAS operators approved by the relevant authority to conduct operations deemed to be a higher security risk per Section 2209 of the FAA Extension, Safety, and Security Act of 2016.

• Providing an exception to the restrictions and requirements for carriage of specified quantities of hazardous materials for delivery by holders of a Remote Air Carrier or Remote Operating Certificate, to allow carriage of limited quantities.

• Additional requirements for agricultural ops would be brought forward from Part 137.

The ARC also recommended that the FAA adopt a non-mandatory regulatory scheme for third party service providers (3PSP) to be used in support of UAS BVLOS operations. The ARC says the FAA and NASA should conduct a study to determine what level of aircraft operations in a defined volume of the airspace might trigger the need for mandatory participation in federated or third party services.

BUT WAIT…THERE’S MORE

The massive, single-spaced report covers everything from environmental recommendations to spectrum, cybersecurity, counter-UAS and network Remote ID.

While the global industry and the FAA mull over the report’s consequences, the ARC hopes for an interim pathway. Such a runway could allow small-scale operations without significant environmental impact while the FAA continues its waiver and exemption process pending finalization of any future BVLOS Rule.

The walk continues in the “crawl, walk, run” that sums up the UAS regulatory process. But the ARC report situates BVLOS at a pivotal moment. “This ARC report represents a watershed moment for the future of American aviation—whether we embrace the future of aviation and allow society to reap the benefit of drone services, or whether we get left behind relative to our global peers,” said Lisa Ellman, partner at Hogan Lovells and executive director of the Commercial Drone Alliance. “The many social benefits of UAS cannot be fully realized without a regulatory structure that enables safe, expanded, efficient and scalable BVLOS operations.”