Hurricane hunting gets better and better while the experience stays the same.

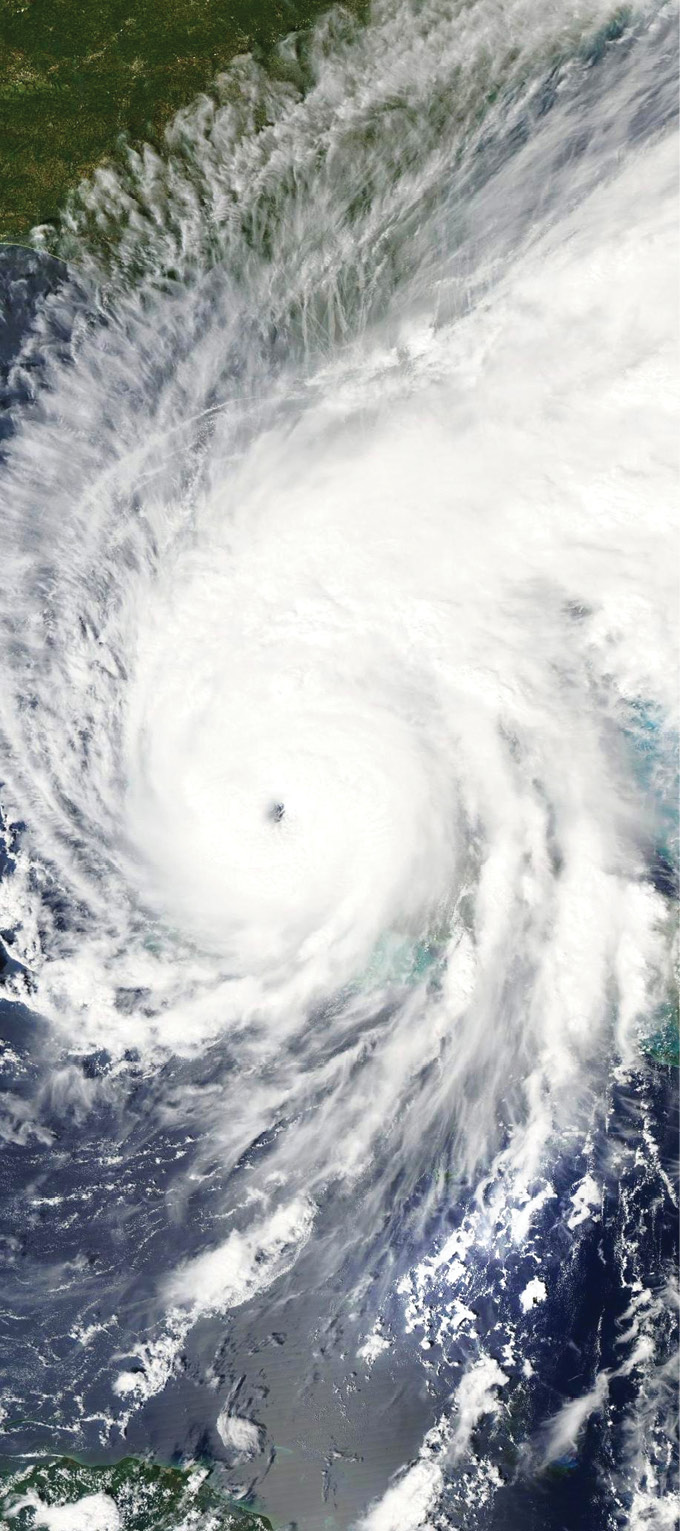

Michael “Izzy” Israelitt never thought he’d follow in his father’s footsteps; and yet, as he spends his days dropping increasingly sophisticated drones into hurricanes, that’s pretty much what he’s doing. Both Izzy and his dad were and are part of the ever-evolving yet remarkably unchanging world of hurricane hunting, a partnership of public and private resources aimed at providing people in the path of storms the best possible information to help protect their lives and property.

Izzy’s father, Mark Evan Israelitt, was a hurricane hunter for the Air Force 53rd Weather Squadron in the late 80s, “before I was born,” Izzy said. Their mission was to fly into tropical storms and developing hurricanes and collect weather data for the National Hurricane Center to improve reporting and predicting models.

Growing up, Izzy would hear about his dad’s history, yet “I had no interest in the military,” he said. “But when I was in college, I realized I was looking for a mission that was greater than myself.”

He joined ROTC and commissioned as an Air Force Special Warfare Officer and Terminal Attack Controller. After his service, he was recruited by the Atlanta wing of Anduril Industries, where he now works as a mission operations engineer, managing the developmental hurricane-hunting program and dropping Anduril’s ALTIUS drones into hurricanes.

“Our goal is to get UAVs into the boundary layer of the hurricane ecosystem,” he said.

Izzy’s father deployed dropsondes—weather devices that drop to the surface collecting data of the surrounding atmosphere that is radioed back to the aircraft, but are limited to where gravity and the wind take them.

Today, the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has taken the lead role in hurricane hunting in the United States. While they still use the dropsondes, they’ve recently been relying on maneuverable unmanned aircraft to gather more and better data.

HURRICANE HUNTING, NOT STORM CHASING

Many people conflate hurricane hunting with storm chasing, a word that conjures up civilian thrill seekers and photographers who hunt tornadoes, not so much hurricanes, in ground vehicles.

“There is a big difference between storm chasing, which is terrestrial based, and what we do,” said Dr. Joe Cione, lead meteorologist at the Hurricane Research Division at NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Lab.

“What we do is hurricane hunting,” he said. Hurricane hunting dates back to 1943 and Maj. Joseph Duckworth, who, on a bet that he could fly through a hurricane, flew into a storm near Galveston, Texas. The weather officer asked him to repeat the flight to collect much-needed data, which ushered in the modern era of collecting data from the air. Before this, the only information on a hurricane’s intensity and path came from ships, but World War II was on and ships were required to maintain radio silence. Hurricane planes and pilots, and ultimately today’s hurricane hunting drones, evolved from that flight.

In the 1940s, most hurricane hunters were Navy and Air Force pilots. In 1970, NOAA was formed and oversees non-military hurricane hunting operations today.

UNCHANGING MISSION

Something that hasn’t changed in many years is NOAA’s mission, which is to protect property and save lives. What also hasn’t changed, perhaps surprisingly, is NOAA’s use of Lockheed Martin’s WP-3D Orion four-engine, turboprop airplanes.

NOAA has two of the aircraft, which are affectionately named Kermit and Miss Piggy. Each incorporates numerous features to collect weather information. They’ve been flying for NOAA since 1976, Cione said, and he expects to keep them in service until at least 2030, when “we’ll have replacements identified.”

NOAA currently launches Anduril’s ALTIUS drones and this year added Boulder, Colorado-based Black Swift Technologies’ S0. NOAA also uses unmanned surface vehicles from Saildrone, as well as dropsondes from the Finnish company Vaisala.

“The reason we’re working with uncrewed systems,” Cione said, “is we need data from the surface of the ocean to a thousand feet up. That is where a lot of the heat and moisture from the boundary layer that is fueling the intensification or development of the tropical hurricanes happens.”

IN THE P-3

The experience of riding in the back of the WP-3D to drop a drone through a chute is also something that hasn’t changed for a while. Drone operator Jack Elston, founder and CEO of Black Swift Technologies, described the experience of riding into the hurricane in the P-3:

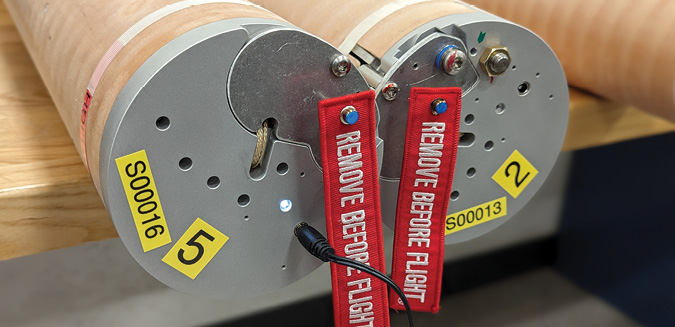

“The flights included maybe 17 people, drone operators, NOAA scientists, pilots, navigators and others,” he said. There are two chutes on the plane—one large for the drones and a smaller one for dropsondes. The Black Swift and Anduril drones fly on different days and use the same chute.”

It can take a few hours to get to the storm where NOAA scientists do their final planning based on radar images.

“Everyone’s operator stations are designed to be bolted down and in reach. So I’ll go through a pre-flight checklist, someone else turns the drone on, and we go through steps to make sure it’s ready to go. There is a countdown, the drone gets dropped through the chute and then it’s up to me to look at the computer screen, make sure everything is going okay and command the aircraft further to do what they want it to do,” he said.

“The drone is contained within a tube. A timer goes off when it gets pushed through the bottom of the aircraft and when it’s clear of the P-3, a parachute drops out to orient it vertically. The outside of the tube falls away and the wings pop out. When it’s ready to fly, it releases itself from the parachute, takes off and starts executing its mission.

“The station we use in the P-3 has a window so you can see the really cool stadium effect of the clouds around you. It’s pretty turbulent through the rain bands, and then you go into the eye,” he said.

“Generally, on the P-3 flights they’re trying to figure out the exact center of the hurricane and then the hurricane’s speed. So, they do a kind of crisscross pattern across the eye to try to determine where the minimum winds are. During that, they drop dropsondes and we drop the drones.”

NOAA’s Cione said all the drones are launched from the crewed aircraft and he doesn’t see that changing anytime soon.

He said there were some examples of flying a plane into a hurricane much lower than is done today. “We did fly an Australian drone from a long way off into Hurricane Ophelia in 2005 and it was a remarkable feat of technology. It flew for 19 hours, but was only able to spend three hours in the storm. The satellite communications didn’t work that well and the drones weren’t really suited for saltwater or salt air for that long,” he said.

“We realized that wasn’t the best thing to do, but the science still calls to us for the information and that’s why we developed the drones.

“There is other technology that is emerging, and I’m looking at drones that don’t have to be dropped out of a plane,” he said. In the future there might be drones launched and piloted from land thousands of miles away but that is not a current capability or practice.

BETTER DRONES

If the P-3 operation hasn’t changed much over the years, what has changed for the better are the drones, the sensors and the models that tie the information together.

NOAA also had another new tool this year—a new model to help produce hurricane forecasting. Called the Hurricane Analysis and Forecast System (HAFS), it’s better at predicting rapid intensification. It was the first model last year to predict Hurricane Ian would undergo secondary rapid intensification. Next year it will be NOAA’s premier forecasting model.

“Twenty years ago, we were sending more data than the models we had could use,” Cione said. “Now, the models can take in all the data from the aircraft. It’s kind of my job to search out what’s new and what works. We try to transition from the research world to the operational world as we test things.”