The U.S. Navy and Marine Corps are relying on unmanned systems to augment traditional, and more expensive, vessels in the fleet as they seek to counter China.

We’re surrounded by distributed systems—systems made up of networks of connected, smaller units, rather than a large, solo entity. Once singular institutions, such as hospitals and universities, have developed outlying clinics and campuses, while the IT world is running toward the cloud where information is kept on a network of linked computers. The advantages are many—efficiency, proximity, reduced risk, redundancy and convenience.

The U.S. Navy and Marine Corps are following suit these days as advances in unmanned technology, changing mission needs and challenging budgets have resulted in a growing number of unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) and unmanned underwater vessels (UUVs) of various sizes deployed, or on the horizon, to augment traditional (and much more expensive) vessels such as destroyers, submarines, aircraft carriers and cruisers.

SHIFT TO THE PACIFIC

Part of the impetus for the development of UUVs and USVs is a shift in mission. In the fall of 2011, the Obama Administration indicated the United States would be expanding and intensifying its role in the Asia/Pacific regions, particularly in the south, and especially as China grows stronger and more adversarial.

“We’ve been trying to move assets there (the Pacific) for some time now. But there are only a finite number of ships to deploy to various locations. And, ships cost money,” said Steven Wills, navalist at the Navy League of the United States’ Center for Maritime Strategy think tank. “So, there’s been a growing interest in how unmanned systems can help the Navy and the Marine Corps to perform a lot of functions.

“The big challenge in the Indo-Pacific is, of course, the tyranny of distance,” he said. “You’ve got to maintain long supply lines and you need lots and lots of supply ships to keep your ships supplied with fuel, food, weapons and more across such a wide battlespace. So far, we haven’t really done that.”

Wills envisions a future with bases on small islands in the South China Sea and other places. One way unmanned systems could support them would be to bring supplies. In addition, he said, the Navy has thought about actual unmanned combatants. He pointed to the last Rim of the Pacific Exercise, where the Navy deployed four large unmanned surface vessels (LUSVs). In that case, he said, the LUSVs only had communications gear. “But those same ships could carry missiles and supplies, or be used as a floating magazine for weapons,” he said.

At the recent Sea-Air-Space exposition, held in early April in National Harbor, Maryland, and sponsored by the Navy League, several speakers addressed the future of unmanned naval vessels. Vice Adm. Scott Conn, deputy chief of naval operations for warfighting requirements and capabilities, said from fiscal 2024 through fiscal 2028, the Navy is investing in buying and testing unmanned prototypes. In the second five-year period, from fiscal 2029 through fiscal 2033, the manned-unmanned fleet will become reality.

Whether that will be “in time” for any emergency needs in the Pacific arena, such as additional defense needed for Taiwan, no one seems willing to predict.

VERSATILITY

A recently updated Congressional Research Service (CRS) report says unmanned vehicles are among several new additions to the Navy and other U.S. military services. Others include hypersonic weapons, cyber capabilities, artificial intelligence, quantum technology and directed-energy weapons that are being pursued to meet any increased military challenges, especially from China.

UVs, whether on the surface or under, are particularly well suited for a distributed approach as they can be less expensive than manned ships because they don’t need the space or facilities to support human operators, according to the report. They are also versatile as they can be equipped with a variety of payloads such as weapons or sensors and can be operated semi-autonomously, remotely or, in some cases, autonomously. In addition, they can be deployed for long duration and distance.

BUILDING ON THE PAST

The Navy’s interest in unmanned vessels goes back decades, but there has been renewed interest in the past several years. According to the Navy-Marine Corps Unmanned Campaign framework document from 2021, “autonomous systems provide additional warfighting capability and the capacity to augment our traditional combatant force, allowing the option to take on greater operational risk while maintaining a tactical and strategic advantage.” That report offered a vision to “make unmanned systems a trusted and sustainable part of the Naval force structure, integrated at speed to provide lethal, survivable and scalable effects in support of the future maritime mission.”

By the time of that report the Navy had already added two unmanned surface vessels, both called Sea Hunter, as prototypes for the medium and large categories being developed today.

Reston, Virginia-based Leidos built the second Sea Hunter, followed by a vessel called Seahawk, in 2020. Dan Brintzinghoffer, vice president and division manager for Leidos’ maritime systems division, said both have operated autonomously in various trials.

As to future vehicles, “The intent will be that some are launched from subs and some from the surface,” he said. “Right now, we’re in the middle of designing a medium underwater UV by next year, with a payload that could perform intelligence, surveillance, data collection or mapping the sea bottom.”

He added that unmanned vehicles are needed contributors. “The force mix the Navy is looking for is going to need increased capacity and increased capability,” he said, both of which unmanned systems can supply.

UNMANNED BACK-UP

The service expects to finish the specific requirements for the LUSVs this year, according to an April Navy press report. The question remains as to exactly how unmanned these unmanned systems are going to be. Adm. Mike Gilday, chief of naval operations, speaking at Sea-Air-Space, said the systems won’t be fully autonomous right off the bat.

“We are definitely going to have a requirement for crew support on LUSV, or a smaller crew, to handle those things that are just not quite there with maneuvering critical situations,” he said.

At the same conference, Rear Adm. Casey Moton, program executive officer for unmanned and small combatants said, “We are trying to push the boundaries…we don’t want there to be this crutch that we’re just going to fall back on the crew.”

Gilday also said the success of Task Force 59 in the Middle East, which used small USVs to sense the battlespace and create a common operating picture for the U.S. Navy and its partners, had helped evolve his own thinking on the positive possibilities of unmanned vehicles, “especially if small USVs can do ISR [intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance] missions cheaper.”

ON THE SURFACE

Gilday said construction contracts on the first LUSVs are likely to be let in fiscal 2025. The Medium Unmanned Surface Vehicle (MUSV) program will follow. The LUSV program is laying the groundwork for both the hardware for the vessels and the software for autonomous behavior, he said, and the LUSVs might carry missiles that a crewed ship could remotely launch while the MUSVs will carry sensing and non-kinetic weapons payloads. Gilday also said upcoming experimentation could include remote firing, underwater refueling and new payloads for surveillance, electronic warfare, anti-submarine warfare and more.

BENEATH THE SEA

On the unmanned underwater side, vehicles of various sizes are in various stages of development. The Razorback, a medium submarine-launched UUV, is a collaboration between program offices PMS 406 and 408. The Viperfish, also a medium UUV, has similar capabilities.

The medium, large and ultra-large underwater vessels are the newest vessels to be coming on line. The CRS report says these are part of an effort to shift toward a mix of ships that extends capacity to an increased number of platforms and avoids concentrating resources into a smaller number of high-value ships, i.e. putting “too many eggs into one basket.”

NEEDED STEPS

The 2021 Unmanned Campaign framework document that laid out the future of unmanned vessels notes challenges that are still being worked on today as it set out to create the coordinated effort to develop new and innovative systems. The physical platforms of the vessels, according to the document, are only part of the picture and even they require the infrastructure to transport, launch and recover them. Other requirements include information connectivity, appropriate training, common data standards, logistics support, efforts to scale and advances in core technologies such as artificial intelligence, cyber security, endurance and navigation.

Crucial to the effort is an evolution from a platform-centric approach, which focused on particular vessels to a capability-centric approach where work is aimed at a desired result, and capabilities are delivered and updated through a modular and open system environment. According to the document, the Navy and Marine Corps are exploring the full spectrum of opportunity presented by industry, partners and prototyping.

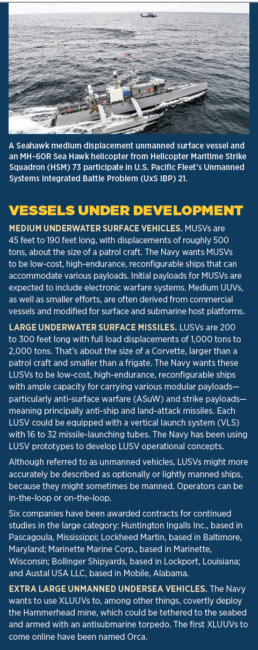

One thing is for sure—the hoped-for end result is to cast a wider, distributed network over the Pacific.