Leading drone airspace security company WhiteFox is partnering in a year-long UAS-defense trial at Canada’s Montreal-Trudeau International Airport. By using the company’s DroneFox technology, the arrangement adopts a nuanced approach to counter-UAS and continues the expansion of WhiteFox’ customer footprint.

“This evaluation at Montreal is one of the largest, longest-running threat-technology tests at a Western airport,” said Luke Fox, CEO of WhiteFox. “They are saying, ‘Once we have the data, what can we do to make better-informed decisions about operations? Do we need to shut down the airport, or one runway, or not at all?’” Public safety specialists BlueForce UAV Consulting and Exo Tactik Air Support also will inform such decisions.

The project represents an ongoing expansion for the five-year-old WhiteFox. It’s primarily served government and public safety institutions, mostly overseas, but is now engaging privately-owned facilities: prisons, power generation, stadiums—and airports. Managed by Aeroports de Montreal (ADM) Montreal-Trudeau serves more than 20 million passengers annually.

Speaking from WhiteFox’ headquarters in San Luis Obispo, California, Fox voiced a reality today’s air hubs face. “At every international airport we see multiple drones flying dangerously close to the airport facility if not directly across the facility. That’s not including all the drones just within the no-fly zone. We can make better-informed decisions about how to deal with them when we have better data.

“Counter-UAS is about knowing where drones are and doing something about them,” Fox said. WhiteFox, however, challenges approaches taken by other types of operations. “Traditional kinetic responses are difficult, expensive to operate. Jammers take out everything,” Fox asserted. “Our approach is designed for dense urban environments, designed to take control of the individual drone and re-route it.”

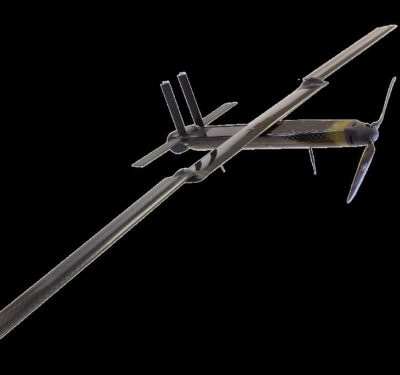

Automated and easy to operate, DroneFox employs a three-pronged strategy. During the detection phase, multiple bands within the RF spectrum are analyzed to differentiate between authorized and illegal drones. Identification, the second phase, involves forensic threat analysis to confirm drone type, payload capacity, the number of times the drone has been seen in the area, pilot location and the like, yielding a “drone fingerprint” to check against a whitelist. That determines whether a UAV is, as Fox put it, “just in the neighborhood or operated by criminal organizations.” If mitigation is in fact required, DroneFox takes control of an intruder, locking the original pilot out and landing, rerouting or returning the drone without affecting nearby signals.

This approach, Fox said, has an added value. “It completely reframes how people see drones. Today people, when they see a drone, panic ensues. Montreal airport is saying, “We understand drones that are flying near the airport, legally and illegally. The technology that gives us better decisions so we can act accordingly.”

Pursuing that line of thought, Fox concluded with a statement that at first seemed counter-intuitive for a security firm but ultimately made eminent strategic sense. “We love drones. Counter-drone technology is the most pro-drone technology, because we can encourage people to trust them. If you can get people the data to make better decisions and accountability, you can leverage all the potential it offers rather than seeing drones at threats.”