Q: You’ve described yourself as both a “techno-realist” and a “futurist.” How do you see those aligning?

A: If you’re going to look into the future, to be considered somewhat believable you need to inject some realism. There are futurists who have watched way too much “Star Trek.” I feel like I’m a responsible futurist, more grounded.

Q: How does your 30-year maturation timeline fit drones?

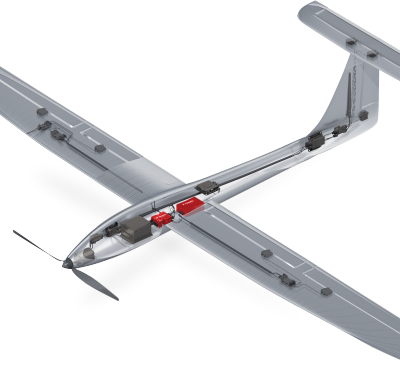

A: The Department of Defense has been working out the drone details since 1990. We’re 30-plus years in now; that seems about right. What was originally a military technology, it’s been commercialized, we’re starting to work the kinks out. Indeed, the drone technology is not the problem; it’s the infrastructure and that type of thing. I think it was 2012 when Jeff Bezos announced that he was going to do Amazon Air Prime; that’s about the time people started really paying attention. So, 22 years after the military started working on them the general public understood that these things are about to become a cultural reality.

Q: What’s the key driver for human-machine interaction?

A: Understanding the right place for shared collaboration, the design requirements and role allocation. Understanding where humans bring the most value, where they can improve overall system performance—and where maybe they potentially add to negative system performance. Unmanned aerial vehicles in the military are so powerful because they take the human out of the dangerous point-man areas. If you’re just one person in an airplane, you’ve got a lot going on. But if you’re on a team of people in [remote pilot base] Creech, Nevada, that becomes the better way to think about teaming in the future. We have the ability to remotely conduct warfare in much safer ways, both for our own people and also people on the ground. The reduction of collateral damage should be at the forefront of everyone’s mind.

Q: What other areas are challenges?

A: A profound lack of training and education in colleges, universities. That runs the gamut from basically understanding the limits of autonomy, being able to code for autonomy. I perceive this to be a national security problem, that we’re just not training enough people who have the right skill sets.

And policymakers need to get smart. If they don’t understand at least the limits and boundaries of the technology, they’re in trouble. This is super important.

Q: What’s your perception of your role in the unmanned vehicle space?

A: I’m very pro-technology. I am trying to get people to step back and understand that when we moved into the world of connectionist AI, deep learning, machine learning, this was a step change of capability and also of risk. We need to make sure we are upping our understanding and our capabilities around safety and certification. That’s a techno-realist point.

MARY “MISSY” CUMMINGS, Ph.D., is a professor in Duke University’s Pratt School of Engineering and director of Duke’s Humans and Autonomy Laboratory. Her research interests include human-autonomous systems collaboration and the public policy implications of unmanned vehicles. She was one of the Navy’s first female fighter pilots—call signs “Medusa” and “Shrew”—and self-published “Hornet’s Nest,” a book about her service experience.

This interview had been edited and condensed.