Keith Miao is the founder and CEO of Birdstop Inc., a San Francisco Bay Area remote sensing company using BVLOS drones and AI to deliver real-time physical world intelligence. Prior to Birdstop, Miao was a data science lead at Google and before that, an analyst in Washington, D.C. He first started working on remote sensing at the Columbia University Earth Institute using satellite imagery and GIS.

Keith Miao, the CEO and founder of Birdstop Inc., began his career working in imagery and data science, “working with satellite imagery to solve some of the problems we’re trying to solve now with BVLOS drones,” he said.

After working in the public sector in Washington, D.C., he moved to Mountain View, California, to lead a data science team at Google before leaving to found Birdstop.

“The idea behind Birdstop has always been, how can we leverage the drone technology that is maturing, but more importantly, beyond visual line of sight, in order to place these flying sensors across the nation and operate them all remotely?” he said. “Creating something that’s akin to a constellation of satellites, but sitting on the ground instead of autonomous flying sensors, hundreds, thousands of miles away in space.”

The company oversees a network of drones across the country, operated from what the company describes as “a NASA-style mission control” in California. It already operates in several states, including Alabama, California and Texas, and is obviously looking to expand.

The company announced this summer it raised $2.3 million to expand its BVLOS drone network and grow its artificial intelligence capabilities. The funding round was led by Lerer Hippeau and included Anorak Ventures, Correlation Ventures, Data Tech Fund, Graph Ventures, Techstars, Timberline Holdings and investors in energy and telecommunications.

“Developments in drone technology and beyond visual line of sight regulation over the past decade are allowing Birdstop’s vision to be realized for the first time,” Andrea Hippeau, a partner at Lerer Hippeau, said in a statement announcing the funding. “Birdstop’s ability to generate real-time intel remotely is a huge step forward for the industry.”

PROTECTING INFRASTRUCTURE

Birdstop’s drones are autonomous flying sensors operating “a few feet away” from their location near an asset.

“We’re providing value right now focused on national critical infrastructure. We identified that as the most important of assets to protect and secure. So, power grid, telecom networks, other energy industry assets,” Miao said.

Later, he foresees expansion into as many as two dozen or more industries.

“All the ones that use drone technology…can all kind of pull into this network. And so, the nodes and the drones that are sitting out there can be servicing a pipeline in the morning, a farm in the afternoon, providing insurance, first response, on demand as well.”

The company has received five waivers, two of which it’s no longer using, for BVLOS flights tied to the operation of its in-house detect and avoid system, which consists of AI-enabled acoustic microphone arrays, computer vision systems, ADS-B and Remote ID, and sometimes radar data.

“A comprehensive tracking system, we call it,” Miao said. “The physical form is a beacon.”

Birdstop has set up a facility in Homewood, Alabama, to manufacture and scale up production of that beacon to meet the growth it expects. “The whole physical assembly will be built there,” Miao said. “You can think of our Alabama location as everything physical about Birdstop. We’ll go through there and everything on the software AI side will stay at our headquarters in California.”

One of the company’s first customers was a telecom company near Birmingham. That led to more work, and eventually the company joined the Techstars Energy Tech program and started working with Alabama Power.

“I guess it was pretty organic,” Miao said of the move. “There was no selection process. It was like, it’s obviously going to be somewhere in Alabama.”

With its previous and existing waivers, and the new construction facility, Miao said it feels like the company is reaching an inflection point.

“To be honest, I think everything up until pretty much this most recent fifth waiver, it’s always been playing catch up with what our customers and what we want do. We’re getting to the point—and we’ve got two more waivers in the works—where it’s kind of like we’re getting almost like pre-approved for things that we want to do, and then we can move our nodes and our customer operations into pre-approved conops.”

Birdstop is using fixed locations for its services now, with “nodes” of drones installed where customers need them.

“We have done some testing of these systems on the back of a truck and whatnot. But the vision is really to have this network that is fixed. And, if you want more locations, we deploy more nodes. ‘Drone in a box’ is one of the industry terms we have been trying to get away from, but it does capture some of the things we’re trying to do, basically building this network of these nodes that are all interconnected, and we try to build them in clusters to give our customers that experience of an interconnected network that can all reach each other and that can eventually hop between each other to cover larger and larger areas.”

Eventually, the goal would be to have nodes located across the country, with customers either managing their own systems or trusting Birdstop to do it.

“Right now, we’re thinking about it as our California headquarters would have a mission control that would be staffed 24/7, and that would oversee the entire network. Some customers—Alabama Power is on this path—[would] do their own mission control for what they want to do. Some larger customers are going to have their own mission control to do their own private fleet of Birdstop, but the vast majority will be managed from our mission control and customers will basically put in requests and they’ll be prioritized, fulfilled, and the data securely sent to their servers.”

Birdstop focuses on its software and detect and avoid system, which Miao said is drone agnostic and can work with a variety of systems. It’s actually aimed at companies that might not really care about what systems are being used.

“The whole premise of Birdstop is really how…to abstract away the robotics, the FAA regulation, just take all of that away from the customer so that if you are managing a power plant, you are just accessing intel on your power plant and not having to worry about drones and all that,” he said.

“We hope that one day our customers never have to touch a drone. Maybe they even forget that it’s a drone providing the intel. We all use Google Maps, but we’re not actively thinking about, hey, how does a satellite imagery map onto my phone?”

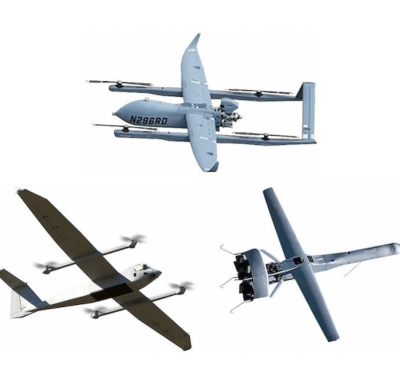

The company doesn’t build its own drones, but uses various off-the-shelf systems.

“The thesis being that drones are going to continually get better, lower in cost, more and more commoditized, and we leverage these as low-cost, competent flying sensors that we can collect data with,” Miao said. “Whether we make or don’t make our own, it will still always be a drone agnostic platform. If somebody else’s drone is best for the use case, we’re going to use that drone.”

Also, not every drone works for every application, he said.

“We recognize that different drones will be for different parts of the network and different customers. A lot of that is determined by the payload as well and what customers need there. We try to be as flexible as possible there, bringing more drones on the ecosystem.”

THE BEACON

The detect and avoid system, which Miao describes as a beacon, includes a variety of systems to serve as what he calls “the eyes and ears on the ground. We have the eyes, which is a computer vision system that’s scanning the airspace through 160 degrees. And we have the ears, which is a microphone array that also has acoustic AI listening to the airspace. That’s coupled with ADS-B [and] other data sources. In certain locations, we have access to radar data, but that’s a luxury, not a guarantee, at scale.”

The combination of audio and visual works well, Miao said; if it’s a foggy day, the acoustic system might bear most of the load, or if it’s a noisy environment, the optical could come to the fore.

“The two things kind of compensate each other and reinforce each other. And, we have a reinforcing model that goes between ADS-B, acoustic and optical that’s able to truth things with either ADS-B data or radar data, and then help reinforce the model. And we usually have multiple models running on the data at the same time, and at a certain frequency, we compare the models and upgrade the models. So, this kind of process has allowed us to continue adding better detection over time,” Miao said.

ENABLED BY AI

The core to all this, he said, is artificial intelligence.

“The AI is what’s looking and flagging different aircraft,” he said. “We’re starting to classify the aircraft as well, starting to identify what the specific models of aircraft are, their trajectory, speed, et cetera. The AI is, in the long term, going to be doing all of it.”

Right now, the model is for AI augmentation for human operators. The AI is popping up alerts and notifications for the remote pilot in charge, and the pilot is also looking and listening to the airspace.

“I think in the foreseeable couple of years, it’s still going to be human-centric with the AI augmenting, but I think in the long run, the AI should be much better,” Miao said. “The AI, I think, is already technically better than the human. It can see things that are pixel changes that a human can’t, it can hear things at certain frequencies that human wouldn’t be able to distinguish a plane versus a truck, where the AI can. So, I think it’s just a matter of getting that better and getting the FAA comfortable to say, hey, the AI is running the DAA [detect and avoid].”

The AI also helps in actually flying the drones. They use GPS for positioning, but that’s not accurate enough for landing on small pads.

“That’s where some of our other competencies and AI come in,” Miao said. “We use a lot of computer vision. We use computer vision to track the airspace, to track for different anomalies on the surface as the drone is flying. And we use that same AI engine to bring the drone down precisely onto a certain location, such as the landing pad of the node. We are using RTK in some of our locations. Alabama, for instance, has an RTK network that we’re able to tap into, [and] other states do as well.”

SECURITY FOCUS

Birdstop is very focused on overseeing national critical infrastructure, Miao said, including the power grid, telecom networks and oil and gas facilities—locations with a lot of distributed assets that face issues ranging from weather disasters to security breaches.

“There’ve been so many things that we’ve worked on, figuring out piece by piece, that right now the really exciting thing is all the pieces are figured out and hence the investors are very excited about what we have been able to accomplish,” Miao said.

“We’ve got these clusters up and running in California, Georgia, Alabama, Texas, delivering value to customers. FAA is on board with it. We’re providing visibility and data to the FAA. It’s all there, it just needs to work all together in a way that’s really useful to customers and, we hope, delightful to use as well,” Miao said.

“I think a lot of our funding will go toward, broadly speaking, making it all just work like magic. Part of working like magic is all the AI that we try to just have running really well in the background. So, we’re detecting anomalies, we’re detecting intruders for security, and it just feels like it’s part of the product.”