While there is great frustration over the slow integration of drones into airspace long used exclusively by piloted planes, unmanned operators are benefiting greatly from the presence of manned aircraft in another arena—insurance.

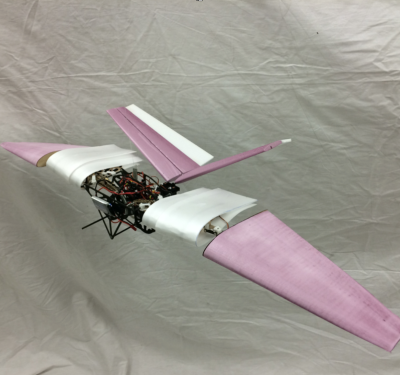

Despite the youth of the commercial drone industry, the business infrastructure and financial capacity it needs to handle risk is already in place because the brokers and underwriters who have supported manned aviation for decades have developed coverage for unmanned activities. This is making it much easier for operators of unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) to protect their business against accidents and devastating losses while doing filming, inspection and other activities. Insurance is also available for their customers, universities doing training and research and others like the entrepreneurs testing out new wing designs and sensors.

“The industry exists today,” said Terry Miller, owner and president of Colorado-based Transport Risk Insurance. Founded in 2003, Transport Risk is an aviation/aerospace specialty insurance broker that got its start insuring the aerial assets involved in film production.

“About five years ago some of our film production clients approached us saying that they wanted to use drones,” Miller told Inside Unmanned Systems. “We thought it was a pretty good idea,” he said, because small UAS would pose much less risk than the helicopters then being used for filming. Miller’s firm began developing insurance products tailored to drone operators, convincing one insurer, then more, to back the policies.

Aviation insurance brokers handle most UAS insurance, Miller said, in part because the courts determined in the case Huerta v Pirker that drones are aircraft and, in part, because insurance is regulated at the state level. That means insurers would have to be licensed separately in every state in which they wanted to operate—a complication they don’t want to deal with for what is still a very small sector. “They deal with specialty brokers… that’s what we do. Our background is aviation and aerospace—that’s all that we do. They prefer to deal with specialists who understand it.”

While brokers have appointments—that is agreements to represent insurance firms in the market, Miller said, the broker serves the client seeking insurance. They present the client’s needs to the insuring firms—usually over the phone or by email—bringing all of the responses back to the client. From these they can make a choice of coverage.

Coverage, Costs

Standard policy coverage limits for a commercial operator, as reported by those who spoke to Inside Unmanned Systems, range from $1million to $5 million.

Those numbers may go up as drones, their sensors and their missions become increasingly sophisticated. Miller said his firm insures actual drone physical damage values and liability limits into the hundreds of millions of dollars. “It is not unusual to see $10 million to $50 million carried on a drone.”

“The highest liability limit we’ve been asked to provide to any professional drone operator is $100 million,” said Chris Proudlove, a senior vice president at Global Aerospace and the manager of UAS risks. His firm, a specialist aviation insurance provider launched in 1924, has aviation customers used to buying $250 million in coverage.

The cost for that basic $1 million policy starts in the high hundreds of dollars annually, according to those who spoke to Inside Unmanned Systems, depending on the drone and its mission. The premium for a $5 million policy would run from around $2,500 to $3,500 or more a year depending on a number of factors including the platform, sensors and intended uses.

Assessing Risk

To better judge the risks they are covering, firms are now tracking losses and asking a lot more questions.

“Over the past five to six years we’ve been revising the questions we’re asking,” Miller said. “It’s been a learning process, obviously, so as we began insuring them (drones) and seeing how they were used, types of changes required for the policies midterm, such as limit requirements. As we started to experience losses it showed us that maybe we needed to ask different questions along the way in our application process to determine the exact exposure as best we could.”

For example, Miller said, they began asking how many over-the-water flights an operator expected to make after one client claimed to have crashed three drones into Florida’s alligator-infested waters in a single year.

“There’s no way to prove they did; there’s no way to prove they didn’t—so they’re covered. We go out and pay for the drones,” Miller said.

Insurance and brokerage firms, including Miller’s, are now building the sort of databases other insurance firms have on cars, campers and planes—marking the track records and repair costs of different UAS models.

“We’re comfortable with many makes and models of drones and are beginning to see a picture of the personality, of what the culture is, among operators of certain types,” Miller said. “Some just have a much, much better loss ratio—that means they’re more profitable.”

Unfortunately that aircraft information is not directly available to drone buyers. Miller said, however, they can tap into an insurer’s experience indirectly by getting a quote on a particular aircraft and comparing that with quotes on other platforms.

Miller said they also take operator training into account and even geographical experience. “We’ve been able to determine over time that there are areas that drones just don’t work in. We don’t know why, but we just see an area that might be a pocket of some kind of signal interference that just causes losses. If we see someone based in those areas, we’ll probably say ‘No.’”

Global Aerospace is assessing risks too, Proudlove said, including researching what a potential client is planning to do with a drone and what kind of built-in capabilities the system has.

“We certainly take into account any embedded technology on the system—essentially, we assess a number of different features of each risk,” he said in reference to geofencing and automated logbooks. “One of the primary things that we look at is the drone itself and how it operates including the level of autonomy that it has. We have found already that drones that rely on a great deal of built-in autonomy are generally safer than those that rely on hands-on flying.”

Stomped

Despite their best efforts, losses still crop up—some in unexpected ways.

“We’ve seen situations,” said Proudlove, “where somebody’s flying a flight one day at location A, and the next day they are at location B— and they forget to reset the return-to-home function. The drone is up at 400 feet and some kind of failure occurs and the drone flies off. The operator is left asking ‘Why is it flying off in that direction? Oh shoot. That is where I was yesterday.”

One drone being used for herding livestock was destroyed by a bull. In another case a homeless man stomped a UAS to bits. During the filming of a feature on snowboarders a bored snowboarder shot a large rubber band at a drone’s propellers. That rubber band got wrapped around the drone’s motor and brought it down.

The latter two examples (and arguably the first) would be covered under a type of coverage called a war endorsement, said Proudlove. A war write-back endorsement adds back into the policy elements that would normally not be covered. In the case of drones, that includes getting stomped and shot out of the sky as well as signal interference, spoofing and hacking.

“We provide that coverage as standard on everything, “said Proudlove. “We generally don’t even ask the question, we just offer it because we provide incredibly valuable coverage under those endorsements. One of the sections under the war endorsement covers hijack. So if the drone was taken over by a third-party—somebody hacked into the system and took control of it while it was in flight—that would be a hijack risk that would be covered under the war endorsement.”

Policies, in fact, are available for quite a variety of risks. Arthur J. Gallagher & Co., for example, has very widely defined policies aimed at universities, which don’t necessarily know all the activities going on in their labs or being undertaken by their students. Gallagher also has been covering beta testing, said Brad Meinhardt, Gallagher’s managing director for insurance and risk management in North America.

Transport Risk Insurance has policies covering drones used in a variety of emergency response, law enforcement, homeland defense and security missions. It even has one for UAS being used for surveillance in correctional facilities. Transport Risk also offers specific coverage for unmanned aircraft being used to assess archaeological sites and do geological exploration.

On the Horizon

Miller’s firm and others also have, or are working on, usage-based policies that provide coverage on an as-needed basis instead of through an annual commitment.

“We can do liability coverage a long-term basis, short-term basis,” Meinhardt said. “For movie production companies we can write drones for one day, two days, three days—a week.”

Transport Risk even has been weighing telematics, which could eventually enable flight-by-flight coverage based, in part, on where the mission is taking place.

“So for example,” Miller said, “today a farmer flying a drone today in Kansas—over his fields, maybe 20 missions a year with very little third-party exposure—would be paying the same amount of premium as somebody flying an industrial drone inspecting bridges in San Francisco, flying over buildings people in cars—200 times a year versus 20 (times a year). So in that case the farmer in Kansas, in our example, should conceivably pay less premiums. He’s flying less with less exposure. The operator in San Francisco, flying in a lot more dense environment from a third-party legal liability exposure standpoint, would pay more. In that case it helps an insurance company determine how much exposure they have and where it is.”

Those kind of innovations could help sustain growth as the industry races forward.

All of those who talked to Inside Unmanned Systems mentioned the surge in the number of policies they were handling after the small UAS rules took affect. Miller, for example, said his firm is now insuring about 7,000 aircraft—a 40 percent jump over the 5,000 they were covering before the Part 107 rule took effect at the end of August. While some of those new policies may have come from companies that were, perhaps, initially operating in the shadows, those who spoke to Inside Unmanned pointed out they had been fielding waves of new inquiries well before the rule was in place.

“I am telling you we are witnessing the industry grow on a daily basis right now,” Proudlove said before the Part 107 spurt. “It’s pretty exciting.”