Minnesota has been experimenting with using drones to inspect bridges for years, and now is creating a curriculum to teach inspectors across the state how to use unmanned aircraft and, more importantly, how to get the best use of the resulting data.

The Minnesota Department of Transportation’s State Aid Bridge program has tapped longtime consultant Barritt Lovelace, vice president of UAS/AI/reality modeling at Collins Engineers, to develop the program’s curriculum, in conjunction with State Aid’s Randy Aamodt, Rodney Carter, Moises Dimaculangan and Dave Conkel.

“They’ve asked us to basically just help the local agencies in Minnesota get started with drones and start using them more, all the way from selecting which drones they should be using and which software, and helping them set up a program,” Lovelace said.

State Aid Bridge engineer Conkel said, “the idea is to develop a presentation and some training handouts and really to just help train local agencies on using drones for bridge inspections.

“We’ll focus on local bridges and the selection of state-of-the-art equipment, drones. They’re going to go over some of the FAA rules so they’re aware of that, And, then some of MNDOT information so that they’re fully aware of what we’re doing at a state level.…”

The two-year contract with Collins calls for the training to be provided online, in-person and in-field, with resources also available that include technical guides and instructional videos, according to State Aid Bridge’s latest newsletter.

“So, a lot of general information,” Conkel said. At the end of the program the state will put out a report, a summary of all the drone inspection efforts and a list of the advantages of using the equipment, and some of the challenges.

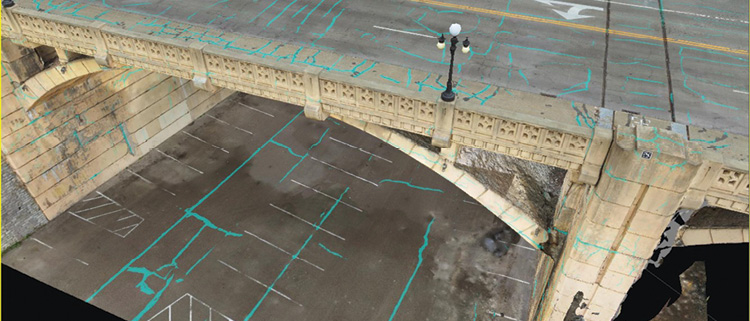

“I think what we’re really trying to do is to take the drone information and bring it back to the office and help them with using that information to improve their inspection reports, possibly creating some models, some 3D models and things like that. So, just kind of trying to increment them up to the next level,” Conkel said.

The state has 47 counties, split into north and south regions. Regional team leader Aamodt oversees the north region with 43 local county agencies and regional team leader Carter oversees the south with 44, an area that contains the state’s largest metropolitan areas. Aamodt said about 20% of the agencies in his region have purchased drones, and Carter said the percentage in his area is similar.

“Our job solely is to assist them with their bridge inspection program so that it meets all state and federal requirements,” Aamodt said. “Some of them are flying drones already…we’ve got other counties that just think they want to get into this, they can see what it can do. They can see that you can do a lot, safely, with not a real big investment.”

The DOT holds annual bridge safety inspection refresher seminars—the latest this February—in four locations and with one online session, and Lovelace “is going to introduce this to the locals, which they’ll be excited about,” Aamodt said. “Just to kind of let them know that we’re here, and this is what you need to do to get up to speed.”

THE NEED

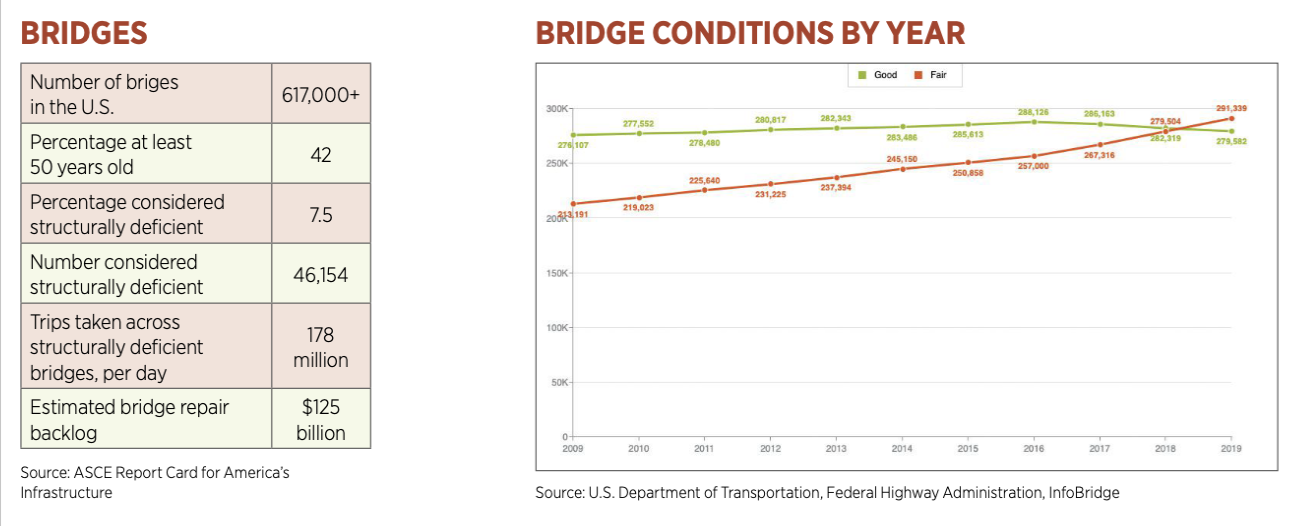

Bridges are, of course, a critical part of the nation’s infrastructure, and maintaining them can be a challenge. According to the American Society of Civil Engineers’ (ASCE) recent report card on America’s infrastructure, from 2021, there are more than 617,000 bridges across the country, 42% of them are at least 50 years old, and 46,154 of them, or 7.5%, are in poor condition, meaning they are considered structurally deficient. ASCE says 178 million trips are taken across these bridges every day.

Minnesota actually isn’t doing too badly on that report card: 4.7% of its bridges are structurally deficient, which is actually pretty good. Neighboring Iowa has a deficient bridge rate of 19%; Rhode Island leads the bad bridge pack at 22.3%, while Nevada, which presumably does not have a lot of bridges, has a rate of only 1.3%.

I first spoke to Lovelace about using drones to inspect bridges in Minnesota in 2017, when the effort was just getting started. At the time, 9.1% of the country’s bridges were deficient, according to the 2016 ASCE report card, meaning 188 million trips were being taken across structurally deficient bridges every day. Compared with the 2021 tally, things are looking up, although the country overall gets a C grade for the condition of its bridges.

“I think Minnesota’s made a lot of progress and has replaced a lot of bridges that maybe had lower ratings,” Lovelace said. “And so, I think Minnesota’s doing very well, and a lot of states are doing very well. But part of this UAS effort is just identifying that we have another tool now that we need to take advantage of because it’s one more way we can access things and find deficiencies, and that technology’s just gotten so much more advanced and easier to use that it’s becoming a pretty common tool for us.”

THE BENEFITS

Back in 2017, Minnesota’s DOT concluded the first phase of a study on using drones for bridge inspection. The state found drones to be a promising technology, bringing time efficiencies and cost savings of up to 66% for some inspections. However, the FAA regulations, which required a Section 333 waiver and a certificate of authorization for drone operations, were found to be onerous, especially for time-strapped inspectors.

Five years on, Lovelace said much has changed. “I think for us it’s definitely a given. We have drones in all of our offices and they get used quite a bit. And I think once our inspectors and engineers start using them in the field, they don’t want to be without them because it is such a useful tool,” he said. “And, there are definitely bridges or places where it doesn’t work, but there’s also a good majority of bridges where it does work well…not really replacing the inspection or replacing our inspectors, but just supplementing it and giving them another tool.”

State Aid Bridge’s Aamodt, himself a Part 107 certified drone pilot, said it’s much cheaper and easier to do at least an initial inspection with a drone before bringing in a Snooper truck with a crane and a basket to lift an inspector.

“You and I could go out with the drone and put the drone up underneath the bridge and nobody would know that we’re there,” he said. With a Snooper truck it could require up to six people and would take up at least one lane of traffic.

Plus, “a drone is relatively inexpensive compared to the latest Snooper truck that the state purchased,” he said. “That one had a price tag of $950,000 on it.”

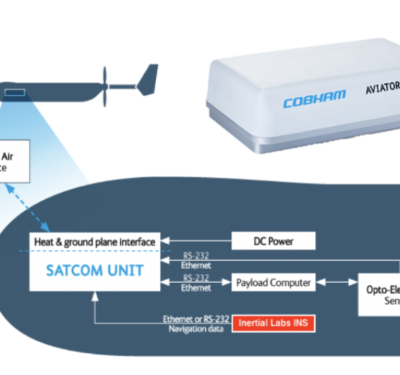

The drone systems have changed as well. In 2017, Lovelace first evaluated the Aeryon Labs SkyRanger, which didn’t work well because it couldn’t look up, then the senseFly Albris, which was designed for building and structural inspection and worked better for bridges.

(FLIR bought Aeryon Labs in 2019 and the SkyRanger now lives on in the form of the SkyRanger 70, an advanced model; senseFly was purchased by AgEagle in 2021 and no longer sells the Albris.)

Lovelace now favors Skydio drones, as he said their artificial intelligence systems—and their ability to look up—helps with maneuvering in tight spaces under bridges, which can cut off the GPS signals some drones need to navigate.

“We’re using those, especially for smaller bridges,” he said. “And we’re even employing their 3D scan app to scan bridges.” He works with infrastructure software company Bentley Systems, headquartered in Exton, Pennsylvania, but with offices and personnel in more than 50 countries, for post processing.

Lovelace said Skydio’s made-in-America provenance is one reason he likes to use their product. “While we aren’t strictly adhering to the blue list, which is more for the Department of Defense kind of thing, we are using American-made drones,” he said, referring to a list of acceptable drones for federal agency use.

Aamodt currently flies DJI drones but is looking into Skydio as well, citing their ability to fly without GPS and to look straight up if needed.

The state training will be “sort of platform agnostic,” Lovelace said. “We do understand a lot of the locals maybe are using the Skydio drones, but really their training could be applied to any drone that they have or get.”

Regulations have eased as well, Lovelace said. “There are still a lot of things that our industry would like to be able to be doing, like flying over traffic and flying beyond line of sight, that are still difficult to get waivers and things for,” he said. “But I think there definitely has been progress and it is much easier now than it was five years ago to go out and start using the technology more.”

PROMISE KEPT

That early promise of drones for bridge inspections has been realized, Lovelace said, as unmanned aircraft can speed up an inspector’s work or at least create more useful data. “I think it does speed up their work, and by doing that, sometimes it just means that we’re able to collect better data because of the efficiencies,” he said. “So, at a minimum if we’re still spending the same time in the field on the inspection, we’re getting much better information than we were in the past.”

Five years ago, Lovelace said he wouldn’t have been able to create this same type of educational program for Minnesota, as the level of equipment just wasn’t there..

“No, I think it would be really difficult. I think early on, if we could identify people that were, you know, kind of techy or nerdy and really want to dig into it, then we could make those people successful. But now we can make almost anybody successful with the drone and almost anybody can fly it.”

THE FUTURE

Lovelace said one new feature has intrigued him—the ability to do high-resolution scans of bridges using augmented reality goggles, which lets operators see a lifelike virtual model of a bridge. “There a few different reasons why we would do that. A lot of times your designer is in a different location and maybe can’t visit the field, because of location or maybe if somebody has a disability. Just not everybody wants to be in a snooper or hanging from ropes. So, we can get all those people involved in the inspection and they’re seeing the information firsthand instead of trying to interpret it from an inspection report.

“…I wouldn’t say it 100% replicates being in the field, but it starts to approach the quality that you might see in the field.”

The upcoming Minnesota training course will include a mention of it, Lovelace said. It’s a more advanced use, but some agencies might be ready for it, “so we’re going to try to encompass all that in the training.”