In this issue’s Law-Tech Connect™ column, Dawn Zoldi does a great job detailing the large number of organizations involved in drone research these days. Every one of them is performing important work to make drones part of our everyday future lives. However, not all drone research organizations are created equal and, unfortunately, I do not have space to address all of them.

Hence, I will cover the “big three” being run in the United States to explain how they feed into the rulemaking process and rate how much they have impacted U.S. drone rules to date. Each happens to be led by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). One is the Center of Excellence (COE) for Unmanned Aircraft Systems, the Alliance for System Safety of UAS through Research Excellence, or ASSURE for short. The other two are the FAA’s UAS Test Site Program and the FAA’s Integration Pilot Program (in its second iteration, the IPP is now called BEYOND). Together, these programs are the bedrock of UAS research in the United States. Collectively they spend hundreds of millions of dollars of public and private funding, utilize thousands of square miles of airspace and create thousands of jobs. But how do they work together to support rulemaking and best practices for the UAS industry?

THE BIG THREE

ASSURE: At seven years old, the FAA’s UAS COE is the oldest dedicated drone research organization in the agency. Managed by Mississippi State University, ASSURE comprises 24 research institutions and more than 100 industry/government research partners. ASSURE spans four countries, involving universities from the United Kingdom, Canada, Israel and Singapore. ASSURE has received $72 million in funds from the FAA to date and matches each dollar with either industry or university funding, giving ASSURE a respectable $144 million research budget. ASSURE’s role is part of the “trinity” of technical drone rule and standards-making. The other two parts are the FAA, which provides guidance and writes rules, and the standards organizations, mainly ASTM International and RCTA, that write industry-consensus standards to support FAA rules. ASSURE provides the basic research to base both rules and standards upon.

FAA UAS TEST SITES: The sites have been established since 2014 and provide safe airspace and resources to test new UAS, try out new concepts and verify if new standards are viable. Unlike ASSURE, the UAS Test Sites get comparatively little FAA funding and are largely self-sustaining. Consequently, the test sites do not do basic research themselves and generally help commercial UAS companies test new business concepts, verify compliance with existing UAS standards and provide a professional team to support customers such as ASSURE, NASA, the Department of Homeland Security and, occasionally, the Department of Defense as they flight test UAS or supporting systems.

The test sites provide all non-propriety test data to ASSURE and the FAA to support statistical analysis. Beyond this basic characterization, it is difficult to directly correlate how the individual test sites support rules and standards development.

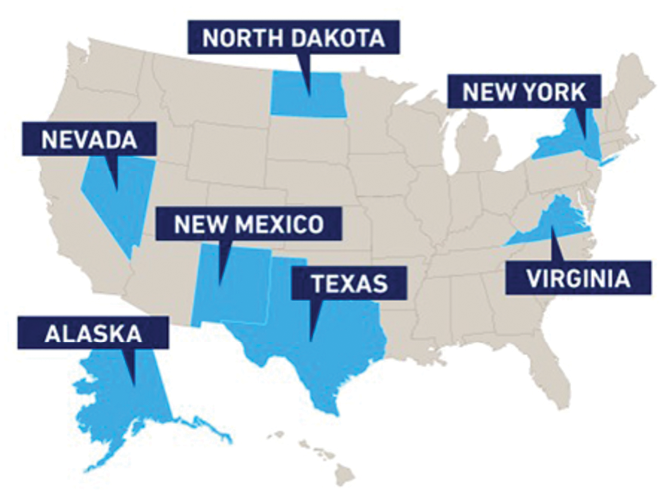

Some of the sites are co-located in ASSURE university states such as the New Mexico State University (NMSU), Northern Plains UAS Test Site (NPUASTS) and the Pan Pacific UAS Test Range Complex (PPUTRC). Some are run by their states’ departments of commerce and help grow local UAS capabilities, including those of the Northeast UAS Airspace Integration Research Alliance (NUAIR), Nevada Institute for Autonomous Systems (NIAS) and NPUASTS. And some indirectly contribute to UAS research advancement by being part of the FAA’s IPP, and those are the Mid-Atlantic Aviation Partnership (MAAP), NPUASTS and PPUTRC.

INTEGRATION PILOT PROGRAM (NOW BEYOND): The FAA set up the IPP as a three-year program at the direction of the White House in 2017. The main goal was to sort out the role of state, local and tribal authorities with respect to the integration of civil and public drone operations into the National Airspace System (NAS).

In October 2020, at the sunset of the IPP’s three-year mandate, it was revived and renamed as the BEYOND program to focus on beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) operations. BEYOND shares some legacy common goals with the original IPP, but its main purpose is to concentrate on streamlining the development of a specific rule versus exploratory flying under existing rule waivers.To me, as a political science major, the IPP and now BEYOND are the most interesting programs because they are the only FAA programs designed to directly address what I see as the elephant in the room—how federal, state, local and tribal authorities work together to make rules to enable scaled and economically viable commercial UAS operations.

ASSURE and the UAS Test Sites have it relatively easy in supporting rules and standards; there is a clear path to rule makers in the FAA and standards makers in ASTM/RCTA. Engineers in ASSURE and the UAS Test Sites are generally talking to fellow engineers at the FAA and standards organizations using hard data to prove their points.

Not so in the IPP. True, participants do have a single federal rule maker to address, but there are 55 states/territories, 310 cities, 570 Native American tribes and 3,242 counties that may, or may not, impact U.S. drone rulemaking. How can you get these organizations all moving in the same direction on drones? ASSURE can provide volumes of useful hard data to support impact limits for drone operations over people, but what hard research data can answer whether or not cities can zone drone operations like they do vehicular operations? Can test flights tell us the altitude at which aerial trespassing ends and federal airspace management begins?

There are some organizations that help harmonize local laws. Lawmakers often listen to the Uniform Law Commission—which drafts non-partisan legislation that multiple states can adopt—when making rules. The nation’s mayors take advice from the U.S. Conference of Mayors and county commissioners listen to the National Association of Counties. Native American tribes have been independent entities for thousands of years and, depending on the treaty they signed with the U.S. government, may be completely self-governing. Indeed, there is a reasonable legal argument that some tribes do not have to comply with FAA rules.

FAA UAS test sites provide safe airspace and resources to test, try out and verify new UAS standards.

OPS OVER PEOPLE

So how do these disparate organizations work together to help make rules and standards? Let’s look at how they helped with one of the biggest roadblocks to commercial UAS operations: the prohibition of drone operations over people.

Research support to the operations over people rules is straightforward considering the massive safety and social issues involved when drones and people mix. The FAA followed a rational process to draft this rule. First, the FAA asked ASSURE to find out if there even was a problem with drones flying over people and, if there was, to define when the problem had serious consequences.

Because the FAA wanted to draft the ops over people rule quickly, they asked ASSURE to do a two-phase UAS ground impact study. The first phase devised a methodology to measure when drones impacting people would cause serious injury, and tests involved the same crash dummies used in automotive testing. This phase supported the FAA’s publicly proposed operations over people rule but, unfortunately, created controversy when the FAA’s draft drone impact measurement methodology was overly conservative.

Enter phase two of the ASSURE study, which thoroughly tested the first-phase impact methodology—but this time with actual human cadavers. The final ops over people rule is not out, but rumor has it the second phase of the ASSURE study directly convinced the FAA to make changes to its draft impact methodology. That is precisely how it is supposed to work.

Once the ASSURE UAS ground impact research showed drone impact was a problem, the FAA made it clear operators would need mitigating measures to reduce the risk of serious injury in a drone-human collision. At this point, ASTM became engaged to developed industry standards for the most likely mitigating measure—drone parachutes. However, unlike the FAA’s role in regulation—which is to state broad performance-based standards drones must comply with to fly over people—ASTM had the much more difficult task of getting industry to agree on how to comply with those standards.

Enter NPUASTS. The good folks in North Dakota quickly approached ASTM and offered their services to both test drone parachute standards as ASTM developed them and then test system compliance with the completed standards. This was a perfect use of a UAS Test Site; not to do basic impact research or to gauge public response to drones over people, but to actually fly drones in a test environment and provide hard engineering data to the folks writing drone standards.

The FAA did not need ASSURE research to tell it that public acceptance of drones over people would be an issue, or that harmonizing state, local and tribal responses to drone operations would be a massive challenge. Enter the IPPs to begin the interesting part of drone rulemaking where test, research and engineering data in general has no impact. Or does it?

CONTINUED STUDY

Unfortunately, the first round of the IPP was not around long enough to fully answer the big questions about what state, local and tribal governments’ optimum role should be in drone regulation, but they darned sure made some interesting approaches to the problem.

The participating IPP government sites went at the problem from two directions—one approach assumed state, local and tribal drone regulation was a must and the other assumed that rational federal drone rules would obviate the need for state, local and tribal regulation.

Teams from both schools of thought rolled up their sleeves and thoroughly engaged their communities with interesting, but inconclusive, results. The high-UAS-profile Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, for example, knew that the delicate relationship between the federal government and some of our Native American tribes would require hard data to convince their audiences that drones are for good and not just another annoyance—or worse, not another surveillance tool.

To move forward, its team collected invaluable information on public perception about when drones became a nuisance. Its data indicates that people tend to lose interest in drones they can’t see and that it is tough to see a drone flying over 200 feet. Also, people in general liked the concept of drone low-risk transit routes that kept drones over safe areas and away from people during transit.

Because of this, they saw a role for local regulators setting up “highways in the skies” for drones flying below 200 feet.

Virginia Tech’s IPP team took a different approach—it proposed that, with solid corporate outreach to local authorities, rational federal regulations were the only thing needed to make drone ops over people a reality. Virginia Tech, working with Wing (a subsidiary of Alphabet, Inc./Google) proved its approach could work with actual drone package delivery operations in Blacksburg, Virginia. Just as theorized, people seemed to lose their fears and negative perceptions when they experienced the benefits, and local authorities were somewhat relieved to not have to involve themselves in drone regulation.

Oh, and Wing decidedly avoided low risk transit routes. People in general like those routes, but specific people living near the routes were not so fond of them. Wing’s solution? Randomize routes over safe areas.

Regardless of which policy solution the nation decides to pursue, the thorny issue of infrastructure cost remains. Here, the active NPUASTS program and the North Dakota Department of Transportation (DOT) IPP, assisted by ASSURE’s University of North Dakota program, are leading the nation in defining commercial UAS infrastructure needs for command and control. North Dakota is spending roughly $30 million to build a ground-based sense and avoid, command relay and ADS-B/UAS remote ID network to support commercial UAS BVLOS operations across the state. This is an extremely admirable, necessary effort, but it begs the question of future funding. Few states have the oil revenue of North Dakota to invest in UAS infrastructure.

The state/local/tribal versus federal issue is key for UAS infrastructure as well. Why is a state paying for BVLOS infrastructure? The FAA pays for the manned equivalent of North Dakota’s BVLOS network; why shouldn’t it pay for the unmanned version? Should localities tax UAS operators to support expansion? Should this be a completely commercial infrastructure?

Or, as the North Carolina DOT advocates, should we use the airport model to pay for it? The Airport Improvement Program (AIP) has been around since the early 1980s and uses federal funds to help pay for airport safety, capacity, security and environmental concerns at designated airports.

Of course, it doesn’t pay for everything associated with airports but it does supplement landing fees and other means used by private or local government authorities to keep our airports operational. It’s another example of an issue research data cannot solve, but one that having state/local/tribal/federal/ commercial partners working together in a structured program might just be able to answer.

BEYOND AND ABOVE

The FAA has very wisely extended the IPP with the BEYOND program, in which eight of the original IPP teams will participate. Granted, I may be prejudiced because I pay more attention to the political impacts of drones over the engineering behind them, but I think BEYOND is the most important FAA drone research organization currently underway. ASSURE and the UAS Test Sites are now-mature organizations with well-developed tasking mechanisms and a clear path from their research and testing to rules, standards and compliance. All they need is time and funding to help the FAA with the other major drone regulation issues, particularly beyond visual line of sight operations, urban air mobility and air traffic integration.

BEYOND has a bigger problem with more involved stakeholders, many with tremendous political power to add complications. BEYOND cannot rely on hard data to the extent ASSURE or the UAS Test Sites do, nor is there a clear path from research to rules with state, local and tribal authorities. I hope BEYOND embraces this challenge and engages the local authority equivalents of the FAA and standards organizations to help answer their concerns before drones fly in their localities.

Just like ASSURE and the UAS Test Sites do for the FAA, I hope BEYOND becomes a source for help for localities that decide they do need to regulate drones. It is notoriously difficult to get the attention of our nation’s governors and mayors, particularly in the midst of a pandemic, recession and domestic unrest, but I hope the FAA and BEYOND can assemble a group of local government “standards organizations” that will bring data-based drone rulemaking to our local governments.

I think subcommittees of the Uniform Law Commission or National Governors Association will help with state government, the U.S. Conference of Mayors will help with city government and the National Association of Counties will do the same with those jurisdictions. Getting uniformity between Native American governments is a bit more tricky, but I’ll wager if they find that federal drone laws don’t apply to specific Native American tribes those tribes will get commercial drone service before anyone else in the nation. Justice served. Finally.