Bad things happen when critical infrastructure—the diverse and complex assets, networks and systems vital to U.S. safety, prosperity and well-being—fails. Case in point: Texas’ storm-related energy infrastructure lapses in February led to outages that left millions without power, water or food, resulting in more than 100 deaths and an estimated $195 billion in destruction. Natural disasters are but one threat; man-made disasters, including criminal or terrorist activity, are another.

Securing and protecting critical infrastructure against all hazards is important to national security. Yet only recently have federal agencies started to test drones to protect important infrastructure and assets in the homeland. In December 2020, the U.S Air Force announced that Travis Air Force Base, in California, was the first USAF installation to launch an automated drone-based perimeter security system. This February, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Science and Technology Directorate (S&T) went live with an announcement that they have begun work with Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) Air and Marine Operations (AMO) and U.S. Border Patrol, the Department of Defense, the U.S. Coast Guard, the FAA, partners and vendors to test “state-of-the-art aerial surveillance technologies, sensors and capabilities at the northern border.” No similar (public) stories can be found in the private sector, which owns 85% of U.S. critical infrastructure.

Where are the drone centurions guarding the majority of the nation’s most important assets?

THREAT PICTURE

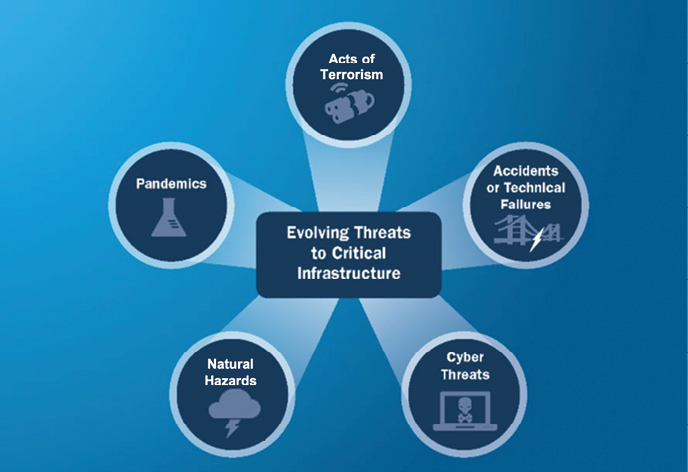

The DHS Cyberscurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) lists 16 critical infrastructure sectors, from chemical plants to nuclear reactors. According to CISA, these all face an increasing range of evolving threats, such as extreme weather, aging infrastructure, cyber threats or acts of terrorism. This, in turn, requires a collaborative approach across the whole of governments and the private sector.

Physical security is one means to protect assets. It generally involves mechanical systems (locks, biometric readers etc.), video and other surveillance, alarms and entry access points. Drones can provide an extra edge.

Pete Cosky, CEO of Cosky Consulting in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, has years of background in drones, counter-drone systems and Red Team operations. “For infrastructure to be safe from any threat, there is a real need to rethink how protection and vulnerability are assessed,” he said. “Guards and cameras are not going to be effective and every detection system has its own set of strengths and weaknesses. There is no magic bullet and without having the particular case looked at from an attacker’s point of view, the end result is false security.”

However, Cosky continued, “there is a viable use case for small drones to be deployed as aerial sentries to cover a larger field of view and prevent those on the ground from easily hiding from a ground sentry or simply skirting the fixed cameras.”

So what’s holding us back?

Sagetech is working with partners to develop certifiable detect and avoid systems to integrate into the National Air Space (NAS).

WORDS, NOT ACTION

It’s certainly not an under-appreciation for the importance of critical infrastructure protection. Current strategic guidance, Presidential Policy Directive-21 (PPD-21), Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience, unambiguously states: “It is the policy of the United States to strengthen the security and resilience of its critical infrastructure against both physical and cyber threats.” The National Infrastructure Protection Plan, and sector-specific plans, circa 2013-2015, elaborated on this vision.

In 2016, Congress linked drones to critical infrastructure protection in the FAA’s Extension, Safety, and Security Act of 2016 (FESSA 2016). It contained several relevant security provisions including:

§2202: Introduced the concept of remotely identifying operators and owners of drones.

§2209: Directed the Department of Transportation to establish procedures for applicants to petition the FAA to prohibit or restrict the operation of drones in close proximity to critical infrastructure.

§2210: Directed the FAA Administrator to create a process for day or nighttime BVLOS operations to protect critical infrastructure and prepare for all-hazard disasters.

Section 2202 ultimately resulted in the FAA’s recent “Remote Identification of Unmanned Aircraft” rule. However, the DOT/FAA have still not implemented §§2209–2210. On January 18, 2021, two days prior to departing office, President Trump signed an Executive Order, “Protecting The United States From Certain Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS),” pushing the FAA to comply with §2209 within 270 days.

The Federal authority is there. It just needs to be implemented.

ROADBLOCKS OR OPPORTUNITIES?

The drone-as-sentry concept is a viable one, despite the lack of implementation of the FESSA provisions and what some might perceive as operational constraints in the FAA’s small-drone rules. The glass half-full view: regulatory challenges present golden opportunities. Here are some examples:

RID: For details on RID, see our previous coverage on insideunmannedsystems.com. RID will take a while to roll out. This is not a show-stopper for centurion drones, but would definitely help with detection. For restricted areas, anything in the kill box should not be there anyway, so RID would not be a huge player.

BVLOS: §107.31 requires the drone to remain within the pilot’s visual line of sight. For some, BVLOS ops remain elusive; others have soared, such as Skydio and American Robotics. That’s what matters.

One-person-per-drone: §107.35 prohibits one person from operating multiple small drones. Infrastructure owners will likely want one pilot to control multiple drones from a command center. This provision is also waiverable. With little to no fanfare, Great Lakes Drone Company LLC just received one in February. It’s doable.

STATING THE GOOD NEWS

State law also must be considered when operating a drone. Most states that have promulgated legislation on drones and critical infrastructure focus on prohibiting folks from flying near them (Arkansas, Arizona, Delaware, Florida, Louisiana, Nevada, Oklahoma, Oregon, Tennessee and Texas). Conversely, Texas HB 912 permits the use of drones for port authority security and surveillance, and to protect oil pipeline and rig safety. In all states, both public and private actors need to carefully consult the law. Where there is none, silence is golden; using a drone as a security measure should be good to go with the right approvals.

TECH IS READY FOR ROLLOUT

Speaking of good to go, fundamental tech enablers for drones are also available, including detect and avoid (DAA) systems. These allow drones to avoid dynamic obstacles, such as other drones and birds, in real time. San Francisco-headquartered Iris Automation, for example, pioneered the first commercial in-flight and onboard drone collision avoidance safety avionics system for non-cooperative objects. This is currently being used in BVLOS flights in Kansas and Canada. Its Casia® 360 will enable greater range.

Sagetech Avionics, based out of White Salmon, Washington, just partnered with American Aerospace ISR (AA ISR) to integrate its first certifiable low size, weight, and power (SWaP) detect and avoid (DAA) system into the AA ISR AiRanger. Sagetech’s system packages multiple core technologies, including a transponder, an interrogator, an ACAS-based DAA computer, software package and essential components compatible with many off-the-shelf low-SWaP radar and other traffic sensors. According to CEO Tom Furey, “Sagetech’s DAA provides a complete solution for detecting and avoiding both cooperative and non-cooperative traffic, designed for certification to the FAA’s emerging TSO-C211 standards. Sagetech’s system will also integrate with non-cooperative sensor input such as Iris’ system.”

Autonomous, or self-governing systems, will also enable drones-on-duty. They take in data, use algorithms and adjust accordingly. Some autonomous systems include artificial intelligence. AI is essentially the machine equivalent of human decision-making. Skydio’s autonomous drones, which include AI computer vision and robotics, are already being used in bridge inspections.

Why not bridge protection?

SOME HAVE ALREADY MOVED

Several companies in the critical infrastructure business already have employed BVLOS drones for inspections. As noted above, select feds have started dabbling in drones-as-security. And now, one company is moving out on the drones-on-duty model to protect infrastructure. Just not in the U.S. yet.

Department 13, with locations in both Columbia, Maryland, and Forrest, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, is using Nightingale Security’s Blackbird fully autonomous drone-in-a-box, designed around flight security with a 30-minute loiter time, to pursue the dream Down Under. Working with Australia’s Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) to gain approval for BVLOS ops, this dynamic duo will provide security to a hydroelectric power energy company in a remote and treacherous environment; namely, mountains prone to roadblocking landslides. Nightingale’s Blackbird can launch in 30 seconds to get eyes on an intruder. Its onboard edge computing AI is capable of detecting people or vehicles and can alert the operator back at a remote command and control location. Department 13 Business Development Director Bill Inman states, “It’s the perfect hands-off way to not only detect but also mitigate a threat situation more quickly and safely than sending a person or a vehicle.” These drones do double duty: besides providing security, they will inspect the landscape and detect potential landslides ahead of time.

So what are we waiting for?

IF THERE’S A WILL, THERE’S A WAY

We’ve got the need, the policy and the tech. All we need is the will. If we find that, there’s surely a way that drones can be used routinely in defense of critical infrastructure. Send in the drones…before it’s too late.