Combining mobile and aerial LiDAR with ground surveying creatively contributed to widening a Florida road near an operating airport on a very tight schedule.

From Disney World to game day for the NBA’s Magic, Orlando’s 2.5 million-person metro area is generating growing demand for increased roadway capacity. But any surveying that involved closing Central Florida Expressway SR 417-149 to widen it would pose major driving issues. Similarly, working with LiDAR would need to negotiate traffic flow and safety, as well as restrictions on UAS flights.

The overall construction plan called for adding two lanes to create a six-lane expressway. A 64-foot median running within 38 miles of existing limited-access toll road would be recrafted into two new lanes and hard-shoulder pavement. Connected and autonomous vehicle technology would be anticipated.

The Central Florida Expressway Authority (CFX) mandated a tight construction timeline, at 18 months. But several complications would affect aerial surveying. UAS could not overfly moving vehicles. Typical line of sight restrictions would be in force. And there was an added concern—SR 417 runs just 2.5 miles from Approach Runway 36 of the Orlando International Airport.

“That’s a very tight timetable,” noted Rob Dannenberg, discipline leader, principal associate, unmanned aviation services of Maser Consulting. Based in Red Bank, New Jersey, the engineering and consulting design firm was charged with delivering the survey data that would allow the Horizon Engineering Group and other builders to move forward. “It’s usually a couple of years, with the survey portion running 4-5 months,” Dannenberg told Inside Unmanned Systems. Everything had to accelerate—and in the event, use of multiple surveying solutions far exceeded expectations, with data delivery in under one month.

SURVEY AWAY

Maser Consulting’s solution integrated manned survey, mobile LiDAR and aerial LiDAR to furnish deliverables in a safe and cost-effective way.

Founded in 1984, Maser now has almost 900 employees situated in 27 offices around the country. It handles small projects, but has deployed as many as 34 crews in the face of heavy storms.

Similarly, Maser’s flying roster has grown from one to more than 55 FAA 107 certified pilots, with even more expansion scheduled. About 15 staffers reside in a dedicated UAS group, which manages advanced sensor deployment and also trains personnel across the company, including those in the more-than-200-person surveying department. “Training a surveyor to be a UAV pilot is easier than training a pilot to be a surveyor,” Dannenberg, who joined Maser almost three years ago, observed.

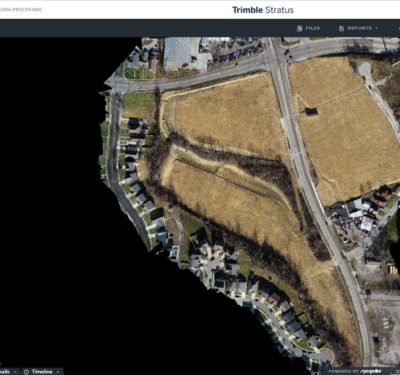

For this project, the goal was to “integrate data to produce high-accuracy, 3-D deliverables.” That meant using mobile LiDAR to capture roadway detail and UAS LiDAR for less accessible areas.

Surveying began in early December, with field time restricted to one week and actual UAS collection spanning just four days in the field. Traditional surveying was combined with truck and aerial LiDAR—but, given timeline and site restrictions, in-air data collection would be held to less than 80 minutes. “If we could fly at 400 feet, I could do 400 acres in one flight,” Dannenberg noted about the constraints. “This took multiple flights and some bunny-hopping at 50 feet, line of sight.”

Nevertheless, survey data was delivered in early January, and included full surveys of the entire right-of-way as-builts and images 150 feet off each side of the roadway.

“The use of the UAVs and mobile LiDAR is a perfect choice for expressway projects, interstate projects,” Joey Roselli, project manager, Horizon Engineering Group, said in a video describing the project. “The fact that you can collect 20-30 acres of data collection in a couple of days—that’s just fantastic.”

INTEGRATING THE PROJECT

Beating the surveying deadline required coordinating multiple solutions.

“We’re leveraging quite a few technologies on this project to capture survey-grade data,” Michael Ehrhart, Maser project manager, said from the site. “Traditional technologies from GPS and robotic…stations, all the way to mobile LiDAR and aerial LiDAR.”

Maser’s aerial armada includes a number of systems to reflect various job requirements (see Maser’s UAS Armada p. 38). This project used the Vapor 55 with LiDAR.

“The Vapor 55 from Pulse Aerospace, in Lawrence, Kansas, is a single-rotor helicopter with the same safety features a real helicopter has,” Dannenberg explained. “We can get a 40-minute flight time—with current line of sight regulations I can fly everything I need to do. We can do 1-2,000 acres a day on the Vapor, safely.”

Payloads also revolved around RIEGL technology, Dannenberg continued. “The RIEGL VUX lineup is the only UAS-mountable LiDAR scanner that can provide basically unlimited returns for vegetation penetration and accuracy. For this project it was perfect. It’s phenomenal on canopy penetration.”

The specific aerial payload was a RIEGL VUX 1. “The biggest challenge is its size and weight, which limits what aircraft you can put it on,” Dannenberg continued. “But the reason is that it’s not sacrificing anything.

“That’s the same scanner helicopters are using,” Dannenberg noted in the video. “If you want smaller segments done and you need richer data or more dense data, we’re a lot lower to the ground…we’re flying a lot slower, so we’re just collecting that much more data.

“Is it cheaper than manned aircraft? I don’t know,” Dannenberg added. “But you’re getting data you can’t get, seeing through vegetation, collecting faster, processing faster, no shadowing.”

On the ground, Maser used a VMX1HA as a LiDAR scan on a truck; the model’s big box and poles collect data as the vehicle is driven. Mobile LiDAR also brought another advantage to the project. “It didn’t need road closures,” Dannenberg said.

Another consideration—safety—was “first and foremost,” noted Maser’s Ehrhart in that on-site video. “Safety for our staff as well as the traveling public.…Working on a limited-access highway, and using mobile LiDAR and aerial LiDAR, we’re not going to access the road surface in any capacity. We’re trying to keep people safe and out of harm’s way.” A two-man crew also ensured that was the case.

The combination of ground, aerial and manned surveying proved potent, Dannenberg noted. “To be able to take aerial LiDAR, mobile LiDAR, conventional survey and see it come together to produce something that I think will be a better engineering product in the end is extremely impressive. It shows where our industry is going and I think it’s gonna make both the design team successful and this project ultimately successful.

“It’s definitely a higher initial investment and not for everybody,” Dannenberg added about the integrated LiDAR solution. “If you don’t know what you’re going to do with something, you probably shouldn’t buy it. But CFX was blown away—we have an entire backlog of Florida expressway projects. It’s become easier to retain clients. They’re happy, they’re not shopping, they’re coming back quickly for data. I went from 1 to 3 units 100% based on demand, not speculation.”

Horizon’s Roselli was equally convinced. “It’s been a fantastic process.…The information provided us is flawless.”