Cyberhawk operatives scanning and monitoring SSEN’s electricity infrastructure.

Routine inspections, while critical across many industries, can be disruptive, costly and even dangerous. Equipment often must be shut down for hours or days at a time, while inspectors are forced to enter confined spaces or take to the skies in a helicopter to gather the information they need.

Inspections also can be time-consuming, so they might not be put on the schedule as often as they should be. That means engineers miss the opportunity to identify and correct small issues, leading to bigger problems that result in more downtime, lost production and revenue, and higher repair bills.

Drones are changing all that. Over the last few years, various industries have started to rely on UAS to complete inspections, whether that means flying over critical assets, buildings and construction sites to collect information or gathering data in confined spaces such as sewers and oil tanks.

These systems are carrying a variety of sensors, including RGB cameras, thermal and LiDAR, to provide deliverables such as orthomosiacs, 3D models, videos and detailed reports that clearly identify issues. Artificial intelligence (AI) is also playing a role, reducing the time it takes to find common defects like corrosion and cracks.

As the technology continues to improve, inspectors who were once hesitant are now embracing drones, with these systems becoming integral to their operations.

“At first, inspectors might have used a drone once every six months; now they’re using them every week because they’re cheaper and more effective than other methods,” said Ariel Avitan, Israeli-based Percepto’s co-founder and chief commercial officer. “They’re trying to find faults before they create failures, so they’re using drones at a much greater frequency and they’re finding more use cases.”

Inspecting Infrastructure

From buildings to bridges, drones are simplifying the inspection process for various structures, providing access to areas once out of reach and improving efficiencies.

Mikel Coulter, an architect who works out of CTL Engineering’s Columbus, Ohio, office, primarily deploys UAS for property condition assessments, or PCAs. When he needs to look at a roof on a building that’s exceedingly tall, is too steep to access or is made of brittle material, he knows he can rely on a drone to gather the information he needs. Drones play a role, whether the site being inspected is a single-unit dwelling or an ultra-large building.

For example, the team deployed a drone to inspect a 120-year-old Victorian home on Ohio University’s campus in Athens,

Ohio, with its steep roof made of Spanish tile. It quickly collected images without operators setting foot on the roof. The same method has been used to inspect large retail box stores, where the alternative is walking the entire roof.

The team also completed an inspection of the Greater Columbus Convention Center, flying over a roof with different levels, shapes and materials. A thermal camera allowed checking for moisture trapped between the roof deck and membrane. Problem spots were identified, signaling where to make repairs.

Building exterior assessments also are made easier with UAS, Coulter said. For example, the team flew the multistory law building at Capital University in Columbus to inspect the granite and sealant joints, without having to rappel down the side of the building.

The tallest building they’ve inspected, Coulter said, is the Rhodes State Office Tower in Columbus. Rather than looking at every window on every floor, they flew the 41-story building to get a closer look at how the windows fit into the skin, and to determine if moisture had settled between the glass.

Inspecting building envelopes and new structures are among the many ways PCL Construction Services takes advantage of drone technology, Orlando-based Virtual Construction Manager André Tousignant said. Drones can reach areas that might otherwise require expensive manlifts and make it possible to complete projects that might take a week or more in just a few days.

PCL uses a variety of drones depending on the task, including the Skydio 2. The drone, which doesn’t rely on GPS, can be flown indoors, and, because of its onboard AI and computer vision capabilities, can fly in complex environments where other drones might run into trouble.

“We can feel comfortable getting close if we need to inspect a building or existing structure,” Tousignant said. “We can do ultra-high-definition building scans, maybe a historical building that we need a good record of before starting construction in terms of cracks and damage. We can take 18,000, 20,000 photos and generate a highly detailed model of its existing condition.”

Drones carrying thermal cameras also can detect heat loss in buildings and the issues that might indicate, said Xinbo Zhang, marketing manager for Industrial Skyworks. Zhang also has clients who look for dangers like beehives hidden on rooftops using the company’s Qii.Ai platform.

UAS-collected data tells workers where and how big the beehive is (one was six sheets), and from there they can safely remove it.

There’s also been an uptick in bridge inspections, said Zacc Dukowitz, who’s with Flyability’s marketing department. Instead of using bucket trucks to access these tight spaces, inspectors can deploy a caged drone like the Elios 2.

UAS can detect cracks in bridges while they’re still small and collect images to create a 3D map to determine if parts need replaced or added, said Ziv Marom, CEO of ZM Interactive (ZMI). Before drones, images of these structures were taken from much further away, and didn’t always provide accurate results.

With AI, ZMI’s solution can be programmed to stay a specific distance from the structures it inspects, whether it’s bridges or buildings.

“Once a month the drone can make the same flight, and the new map is layered on top of the old map to detect differences, maybe a crack,” Marom said. “Then you can do the same inspection next month and in six months to see if the crack is bigger. If it is, you know you need to do something about it.”

Critical Asset Inspection

Drones are proving they can handle various types of assets, efficiently inspecting utilities, solar farms, windmills, pipelines and flare stacks, to name a few.

Cyberhawk performs inspections across the energy industry, and has worked with Scottish and Southern Electricity Networks (SSEN) for about 10 years. First they flew drones with their linesmen to prove the systems could capture the high-quality data they needed, CEO Chris Fleming said, eventually standardizing assessment methods across teams.

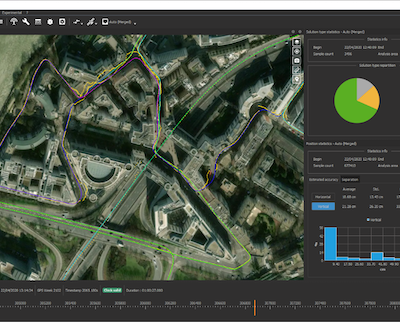

Through iHawk software, which Cyberhawk developed to eliminate cumbersome reports that weren’t easily shared, SSEN team members can visualize and analyze all the data collected across thousands of transmission towers and substations

in the U.K. Everything is stored on the cloud, and work orders can be raised and closed via a tablet. Once a repair is made, linesmen can take a photo with the tablet to close the loop, with everything stored within the software.

Deploying drones for utility work takes helicopters out of the equation, Fleming said. Helicopters have been the go-to remote inspection tool for years, but inspections with them can be quite dangerous, which is one of the driving forces behind increased drone adoption. That, along with the high-quality data and added efficiencies the technology brings.

“Using drones and particularly from a third party allows our internal resource to focus on maintenance work and also reduces the need for any climbing of the structure,” SSEN’s Maintenance and Inspection Manager Martin Bailey said. “A drone inspection team also leaves a lighter footprint than a team who would need to climb each structure and the kit/vehicles required.”

The detailed images and defect gradings allow SSEN to determine urgency and then program repairs into the maintenance cycle, Bailey said.

Percepto, the company behind the Sparrow drone and the AIM platform, is using data inspection to 3D-map industrial sites, looking for anomalies by comparing 3D models taken at different times, Percepto’s Avitan said. Defects can include corrosion, leak, stains and dents.

With thermal cameras, operators can identify anomalies on a pipe, Avitan said. If a pipe that’s supposed to be 50 degrees suddenly spikes to 80 or 90 degrees, that’s a sign of a leak. One of the biggest drone inspection applications in the oil and gas industry is identifying leaks using optical gas imaging (OGI) and other sensors. (For more about this application, read “A New Stage in Oil and Gas” at insideunmannedsystems.com.)

Drones can be deployed to perform inspections across an entire refinery, searching for defects in flare stacks and rooftops, as well as temperature abnormalities in the active core of the refinery. The railroads that bring trains in are also inspected, as are the cranes used around the sites.

“If we map a tank and want to see if there’s corrosion or cracks or leaks, we have already trained our AI to look for black stains or any cuts,” Avitan said. “It looks for specific features, tags any issues and creates a report that’s sent to the person responsible for the asset.”

Offshore oil and gas assets are also ideal for drone inspections, Fleming said, again reducing down time, saving money and enhancing safety.

Wind turbines represent another area where asset owners are seeing the value drones provide, said Randall Warnas, global sUAS segment leader for FLIR, headquartered in Wilsonville, Oregon. Drones can inspect blades while they’re still moving, meaning the only downtime comes when repairs are needed.

Through AI, drones know the structure and shape of the specific turbine they’re inspecting and can fly autonomously in orbit at a safe distance

around it, collecting high-res imagery of defects caused by lightning strikes and hail damage, Warnas said. This removes pilot error and allows for repetition.

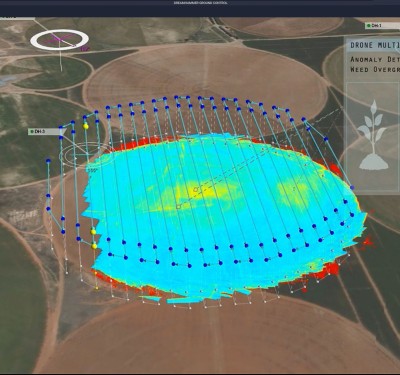

Then, of course, there’s solar. In less than a day, a drone can inspect an entire solar farm—a task that might take a week on foot using a thermal camera on a boom that doesn’t get the most accurate readings, Warnas said. A drone flying above the panels can quickly and accurately identify those that aren’t working properly.

And as automated drone-in-a-box solutions eventually become the norm, Warnas said, asset owners can perform these inspections as often as they want. When one panel goes out others soon follow, so spotting problems early maximizes up time.

As with other assets, solar farm owners typically want a punch list of any problems found, Warnas said, ordered by severity so they know what to address first, and also georeferenced to tell them exactly where to make the repair.

Site Planning and Monitoring

Drones are deployed for inspections throughout the construction process, starting with flights to document a site’s existing condition, Marom explained. Before installing a pipeline or erecting a building, sites are flown using sensors like LiDAR to accurately map the terrain.

“If we have a client buying an existing piece of property, we have to go out and locate all the buildings and utilities and get all the topographical information,” said Joe Stanley, who works in CTL’s Morgantown, West Virginia, office as a project manager, business development. “The drone makes that so much quicker.”

It’s also an effective tool when building onto an existing structure, Tousignant said. The PCL team does this type of work in industrial plants frequently, and can now generate 3D models to pair with design data, adding intelligence to everything. By looking at the structure more closely, it becomes clear if adjustments are needed.

AI can tell if what has been framed up on a construction site is what’s actually been poured, Tousignant said.

“It’s trained well enough to recognize what’s concrete and what’s not,” he added. “It can even go so far as to tell us this column is out of place or the wrong shape, or if it’s formed up as a square and it should be round. It recognizes geometric differences and flags them, so from a quality control perspective we know everything is in the right spot and going according to plan.”

PCL uses Esri’s Site Scan for ArcGIS to acquire, process and manage drone imagery. Once data is uploaded to the cloud, Tousignant can invite engineers and clients to view everything connected with a specific project, or just data and models from one flight. Models can be brought into other software for further insights.

For tracking construction projects, UAS can be used to create progress reports for a terminal being constructed for, say, an oil and gas company or a solar farm. If the client is planning to install 200 panels in a day but the drone only counts 150, it’s clear adjustments should be made.

“AI, machine learning, is fantastic for these jobs because it’s so repeatable,” Tousignant said. “Once opened to Site Scan, a group we work with called AI Clearing will take that data and process it through machine learning algorithms to identify the major parts and pieces of the solar structure and identify everything based on geographic location of where the drone was, and that’s then compared to the actual design data. Within 24 hours after the flight, we have a report and in some cases a live dashboard showing us what’s been installed and any differences noted in that flight versus the previous flight.”

Drone data even can be useful once a project is over, Tousignant said. It provides a record of what things looked like before being moved or before concrete was poured, making it easier to fix problems that arise later.

“Because we’re flying so frequently, we’re capturing things that are eventually covered up,” he said. “For example, we had a job where the utility main had to be relocated. We have images of what the relocated utilities looked like before they were covered up, so we can go back in time to see them without physically having to excavate a property.”

Confined Spaces

Sending people into confined spaces can be dangerous, making it an appropriate job for drones. The team at Cyberhawk performs these types of internal inspections often, including looking for damage inside oil tankers once they’ve reached port and been emptied.

Boilers and pressure vessels are other areas where drones collect visual data, Dukowitz said. The Elios 2 features oblique lighting that inspectors can move around like a flashlight, enabling them to see pitting and other defects. Its 10,000-lumen lighting system and its vehicle stabilization support high-quality images and video, repeatedly.

“If you want to look at a weld alongside a boiler you can stay the same distance the whole way and then inspect two years later at the same distance,” Dukowitz said. “You can track flaws over time.”

Sewers are one of the biggest growth areas for confined space inspections, Dukowitz said. The water that runs through sewers must be diverted so divers can safely go in. If that can’t happen and the flow is too high, the task becomes much more dangerous.

In the past, one way to get around this was to put a CCTV camera on a floating device and drop it into the sewer to collect images. This is limiting both in terms of quality and control, Dukowitz said. The camera is at the mercy of the water flow and can’t be adjusted for closer looks at problem areas.

There’s a sophisticated robotic solution designed for these types of inspections, Dukowitz allowed, but not only is it big—it takes a small crane to get it in the sewer system—it’s also expensive. Drones can more nimbly identify issues for repair.

Mining is another growth area, Dukowitz said, with drones completing inspections before and after blasts, for example. They also monitor many aspects of the work before, during and after an area has been mined, increasing safety and productivity.

Looking Ahead

Easing regulations to allow beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) flights to become the norm will spur drone adoption, Warnas said. At some point, every utility will have drones flying power lines daily, and no one will think twice as the UAS pass overhead.

The work will be the same but the software more efficient, Marom said. Inspectors will obtain even more focused and precise results, with software already built into the drone for specific missions.

Data management also will get easier, Avitan said, with platforms like AIM handling the sifting process with AI. Autonomy will be key, with drones only alerting asset owners when they identify a problem.

Eventually, clients who need a highway or building inspected will expect the company they hire to use a drone, Stanley said. Those who don’t offer the technology will be left behind.

And as the systems continue to demonstrate reliability, asset owners will trust them even more and use collected data predictively, intervening early to save money and improve safety.

“Over time, they’ll get more and more information on assets that are deteriorating to determine their lifecycle,” Fleming said. That’s the ultimate goal. To see what’s failing and how the defects are trending, to predict when things are going to fail.”

AIM Platform

Percepto’s Autonomous Inspection & Monitoring (AIM) platform is an end-to-end solution designed for critical infrastructure and asset monitoring. The company’s Sparrow drone is paired with Spot, a mobile robot from Boston Dynamics. When someone requests data, the most suitable robot will be deployed, without human intervention, to obtain and then stream that data.

This platform limits the number of people needed on an industrial site and allows for remote management, something many of Percepto’s clients wanted, Co-founder and Chief Commercial Officer Ariel Avitan said.

“What we do with the Sparrow, our drone-in-the box solution, we’re now doing with Spot,” he said, noting the data is all meshed into one location. “If the client says I want a thermal imaging report on tank 17, it automatically chooses the correct sensors, collects the data, converts the data into insights and creates a report.”

Sites are divided into points of interest, allowing clients to sift through information such as when the data was collected and the type of sensor used. It’s also possible to subscribe to reports to parse the software results.

Along with the rollout of AIM in the North American market, the Israeli-based Percepto recently announced plans to open a U.S. headquarters, in Texas, this Spring.

Heavy Lifting

ZM Interactive’s xFold Dragon line features drones of multiple sizes that can lift up to 1,000 pounds. When they’re not used for inspections, they can deliver parts to help with repairs as well as other cargo. The drone can change configurations quickly, so clients can use one system for multiple missions. (For details, read “Heavy Lifting: ZM Interactive’s Dragon Series” at insideunmannedsystems.com.)

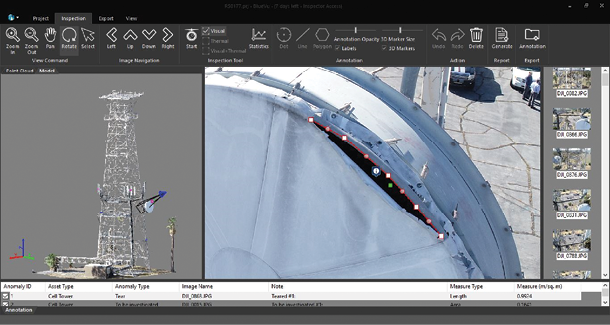

Qii.Ai Platform

This full stack end-to-end platform uses AI to automatically detect defects, said Xinbo Zhang, Industrial Skyworks marketing manager. Asset managers can create digital twins and reports to track an asset’s progress.

Once the data is collected and uploaded to the platform, AI filters out unnecessary images to create a digital twin asset for managers to inspect, he said. It automatically annotates anomalies such as corrosion and creates a shareable report.

With digital twins, clients can perform a preliminary evaluation of their assets to see if further analysis is necessary.