U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s small UAS program has grown to average 28% of the agency’s direct air support hours flown.

Just before Rodney Scott, former chief of the U.S. Border Patrol and a 30-year veteran of the service, retired, he saw just how different platforms could integrate in an operation as he flew over South Texas in a helicopter.

Agents had seen a group of migrants cross the river, but they became difficult to follow in thick cane conditions. Small unmanned aircraft pinpointed where the group was last seen, then backed away as the helicopter came in and was able to pick out the group very quickly.

Without the unmanned aircraft’s ability to direct the helicopter, “it could have taken another 20 minutes,” Scott said. “And that equates to tax dollars long term.”

Drones have long had a role on America’s borders. The use of drones for drug interdiction goes back to 1990 at the southern border. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) began operating a Predator B drone in 2005. Drones play a role in threat identification, operational risk mitigation, search and rescue, terrain mapping, tower and infrastructure inspection and natural disaster damage assessments.

In today’s world of increased threats on both the immigration and interdiction fronts, as well as technological advances, the use of small, portable drones has been on the rise on the borders.

With initial contracts let in 2019, and starting with a handful of systems, CBP’s small UAS (sUAS) program has grown to average 28% of CBP’s direct air support hours flown, and accounts for 48% of air-assisted apprehension events, according to Ralph “Quinn” Palmer, national operations director CBP sUAS, in an email response to questions.

This means an estimated savings of more than $45 million per year in comparison to what manned aviation coverage would cost, he said.

“I understand from our first responder colleagues and partners at the FAA we put more hours and systems in the air at any one time than anyone else in the nation, making CBP the most prolific single user of drone technology within the continental United States,” Palmer said.

DRONES ENHANCE THE MISSION

CBP’s mission is to safeguard America’s borders, protecting the public from dangerous people and materials, and at the same time, enhancing legitimate trade and travel. Drones further the mission in three basic ways: they help cover remote areas, provide real-time information that improves response time and help keep agents safe.

Perhaps most importantly, “drones allow the agents to spend more time on things only an agent can do,” Scott said, “deciding where an activity is on the threat spectrum and interviewing people to decide whether they’re telling the truth.”

Anything CBP can invest in that can buy the agent more time to interview people face-to-face is worthwhile, he added.

And, while people usually think of the border as the southern border of the U.S., and perhaps the northern border with Canada, threats come from all directions and CBP covers the ocean coasts as well.

As Scott explained, CBP works hand-in-hand with the coast guard, with the Coast Guard traditionally covering the deep water farther out, and CBP covering the shallower areas closer to shore. There is, however, much overlap. In addition, CBP teams up with state and local authorities, many of whom have their own equipment to add to the mix. “The sUAS seem to be more effective closer to shore, as you need a platform to launch the aircraft and they don’t have a long duration,” Scott said.

As to the key differences between the southern and northern borders, “That’s easy, weather and dust, Palmer said. “Drones don’t like dust in the southwest but, they also don’t like rainy days and ice in the north either.”

sUAS ACTIVITY GROWTH

The current operating budget for CBP sUAS is approximately $10 to 12 million annually, which covers new acquisitions, training, program support and lifecycle sustainment efforts for the existing fleet, Palmer said.

By the end of the fourth quarter of fiscal 2023, sUAS flew more than 33,349 sorties, or over 14,603 hours of support, with 41,414 apprehensions and seizures of nearly 3,000 pounds of narcotics, 87 conveyances, and 13 firearms. This is a 16.6% increase in missions, 12.6% increase in sortie hours, 29.6% increase in seized narcotics and a 160% increase in seized firearms compared to fiscal 2022, Palmer said.

TASK-FOCUSED SELECTION CRITERIA

As to the selection of UAS, Scott explained how “years ago, we chose to go a slightly different route than the military because we really didn’t have a lot of success with identifying specifications and having somebody build something for us. So, we did two things—we tapped into existing technology that we could get through the Department of Defense, and we put out descriptions to the industry. “We would say something like, ‘We need something that is unmanned, portable and ruggedized. We need something that can see and operate in the environments we face.’ For example, if I have a piece of technology that can see 40 miles, but I’m in a mountainous or hilly environment, then all I see is ridge lines. So, we would walk through those types of situations and requirements as opposed to listing specific specs.”

As to what made the agency turn to drones in the first place, he said, “what it comes down to is what’s the best return on investment.”

For example, he said, the agency already had large Predator drones, but in terms of buying more, they were “ridiculously expensive” and, because people were not shooting at the drones on the border, the smaller drones were found to be more cost effective.

While procurement strategies and specific capabilities are necessarily confidential, “it would be accurate to state we utilize a combination of commercial off-the shelf, government off-the shelf, and DOD systems and deploy them independently and or collectively to those locations where their flight characteristics best correspond to the current operational requirement,” Palmer said.

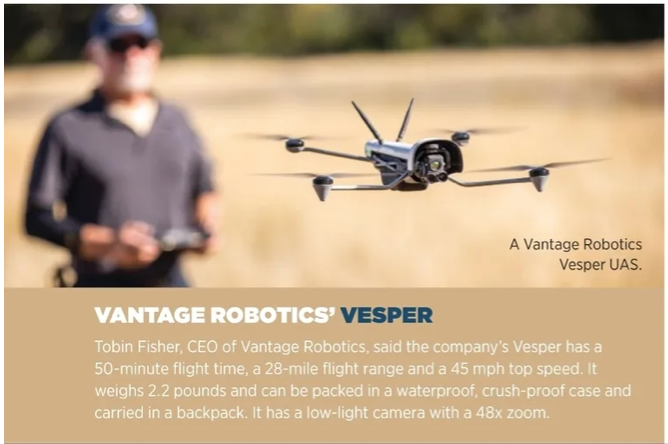

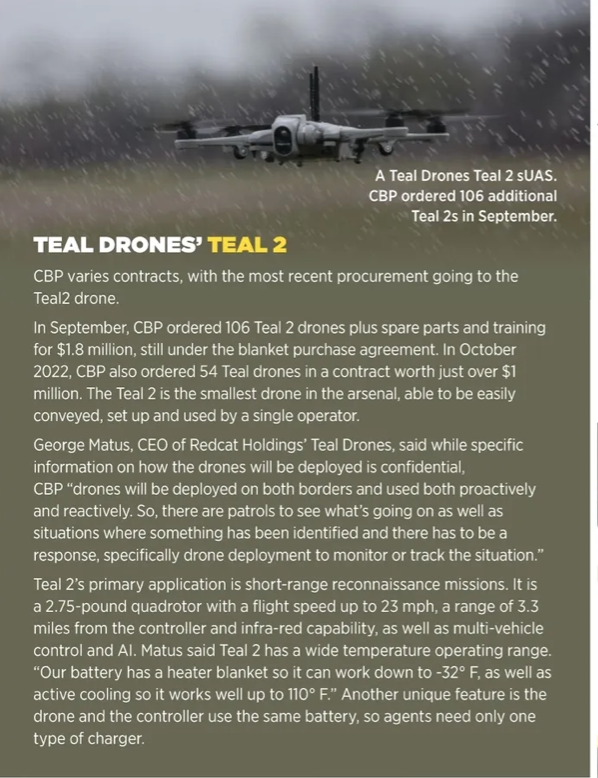

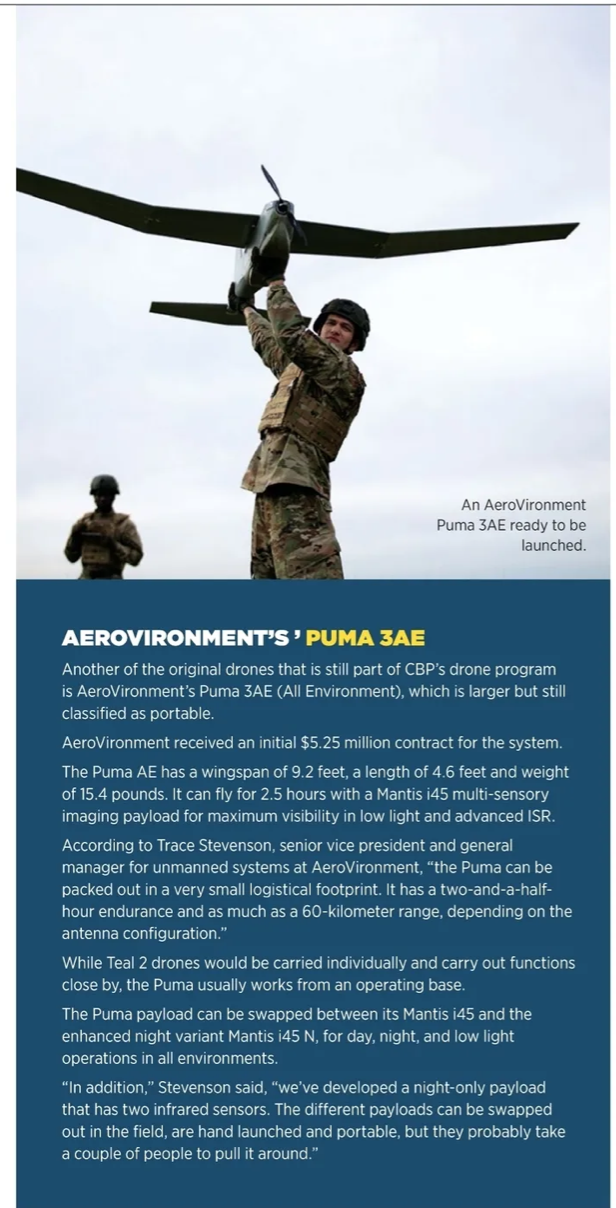

The first large foray into sUAS was in 2019 with a blanket purchase agreement estimated at $90 million announced in 2021. The agreement originally involved five companies. Today, several systems, including Red Cat Holdings/Teal Drone’s Teal 2, AeroVironment’s Puma and Vantage Robotics’ Vesper, are still in the field, along with drones from Skydio and others.

SUCCESSES AND FAILURES

Palmer said successes so far included increased personnel safety, access to more air support, more rapid deployment and the fact that drones are so quiet, “allowing our teams to dictate the engagement with potentially violent or dangerous persons.” He also pointed to success in training and “the level of competence in our operators,” which contribute to both safety and success. He also cited ever-increasing effectiveness and efficiency measures for interdiction rates and diminishing resolution times (that is, recovered agent time—the time an agent needs to respond to and resolve a detection event).

“Success, though, is best defined by the enhancement to the safety of our personnel as the drones themselves are covert, allowing our men and women on the ground to plan and coordinate initial contact with suspected smugglers in a more organized and controlled manner,” he said.

As to failures, “we continue to chase what type or to what degree of beyond visual line of sight would best fit our operational need,” he said. “We have yet to identify industry partners/vendors that could substantially help realize the range and endurance limits of our notional BVLOS use cases, but we are confident and optimistic that a solution is probably right around the corner.”

He also pointed to battery care and maintenance. “We lost a lot of birds early in our program as we did not account for how battery degradation should be tracked and recorded, which corresponded to many in-flight battery failures. Ultimately, we were using our batteries too much and on too regular a basis, and were not tracking the use of our inventories at a level of detail to ensure battery integrity was always at its optimal level.”

TURNING TO THE FUTURE

“We certainly think that drones will be an important tool for control of the border,” Vantage Robotics CEO Tobin Fisher said. “Overall, we’re in the very early days of what’s possible with drones. We’re moving toward increased flight time, decreased cost, increased camera resolution, and increased autonomy reducing the cognitive load on the operators.”

Palmer said, “sUAS technology itself is experiencing dynamic evolution in terms of capability—better and smarter batteries, alternative power solutions, long ranging sensor integrations, stronger and more secure comms links, increased modularity, more resilient and rugged system engineering specifications, system interoperability, etc.

“CBP will always be searching for and participating with American industry to identify those technologies that meet the requirements of the national security mission and in doing so, we look for procurement opportunities that can be responsibly resourced, whether at the price point or the manufacturing point of origin.

“In short, we are beginning to see domestic industry partners build greater capacity and variety,” he said, adding, “Lastly, although certainly not least, we see great advancements being undertaken to cyber harden systems which provide for secure data capture and retention—critical to safeguarding law enforcement sensitive data.”