Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University recently completed a test using DJI’s AeroScope remote ID system to compare drone tracks detected to manned aircraft ADS-B tracks. Why? The team wanted to see if drones were getting too close to manned aircraft.

Is the Federal government moving fast enough on remote ID for small drones? A self-funded, 13-day research project by ASSURE’s Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University provides startling data that indicates that our government must move on remote ID as fast as possible.

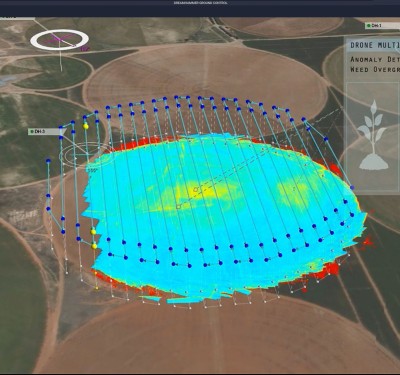

Embry-Riddle’s Ryan Wallace, Kristy Kiernan, Tom Haritos, John Robbins and Godfrey D’Souza had a simple idea: How about running DJI’s AeroScope remote ID system for a few weeks and compare the drone tracks detected to manned aircraft ADS-B tracks to see if drones really are getting too close to manned aircraft? The team mounted an AeroScope antenna on top of a university research building close to Daytona Beach International Airport and let the system collect small drone tracks for 13 days in May 2018. They then loaded the data on to Google Earth and overlaid FAA chart data to determine if remote pilots were flying in accordance with Part 107 small unmanned aircraft system (sUAS) rules. They also compared the drone tracks with ADS-B tracks to see if any remote pilots were flying their drones too close to manned aircraft.

What they found

The results revealed some startling violations of FAA Part 107 rules for sUAS. In the thirteen days of data collection, the team collected 192 drone flights by 73 separate DJI platforms in an area about 10 and a half miles around Daytona Beach airport: 6.8% of these drone flights exceeded the 400 feet above ground level (AGL) ceiling required by Part 107; one drone flew to 1,286 feet AGL; 88% of the flights occurred in residential areas or commercial, public or industrial property, probably breaking Part 107 rules against flying over people; 96.8% of the flights were within five nautical miles (NMs) of an airport and 84.2% were within five NMs of TWO airports. Some drones got within .5 NM of an airport and .35 NM of a heliport. Part 107 tells drone pilots to stay 5 NM away from airports, unless they get permission from airport authorities. Two thirds of the flights were within the Class C airspace for Daytona International Airport. Part 107 mandates drones stay in Class G airspace unless cleared in to Class B, C or E airspace by the airport tower, either by phone or via the Low Altitude Authorization and Notification Capability (LAANC, which wasn’t available for Daytona International until after the study).

Perhaps most alarming of all, researchers detected two near air to air collisions between drones and manned aircraft when they compared the AeroScope drone tracks with ADS-B tracks from manned aircraft. The first near collision saw a drone fly within 188 feet of altitude and 1,800 feet lateral separation of a manned aircraft off the beach near Daytona. Both aircraft were probably towing banners. Researchers concluded that “considering the low altitude and slow speed, it would be difficult for these aircraft to safely perform evasive maneuvers.”

The most dangerous near mid-air collision occurred just 1,500 feet from the approach end of Daytona Beach International Airport. In this case, a manned aircraft passed through the drone’s position within seconds of each other. Researchers surmised that many drones flown near Daytona International come from the nearby Daytona Beach NASCAR Speedway parking lots, Volusia Mall parking lots and other nearby commercial parking lots.

The impact of Geofences

DJI’s geofencing system only partially helped prevent remote pilots from violating Part 107 rules. Geofences are location-specific flight restrictions designed to restrict sUAS flights near areas that would create a security or safety risk, such as airports critical infrastructure, or prisons. Some geofencing zones do not prohibit flight but warn remote pilots about flight risks. DJI’s geofencing provides these warnings (ranked from lowest to highest):

• Warning Zones: A warning message to operators regarding risks contained within the zone.

• Enhanced Warning Zones: Operators receive a message indicating flight is restricted, however, remote pilots can override the restriction.

• Authorization Zones: Operators receive a user interface message indicating flight is restricted, however, the user can override the restrictions by logging into the DJI Go application with a verified DJI account.

• Restricted Zones: Operators receive a user interface message and flight is prevented in the subject zone. Such flight is only accessible with a special unlock code from DJI.

All drone flights detected during Embry-Riddle’s 13 days in May occurred within not one, but two geofencing zones. More than 85% of the flights took place within an Enhanced Warning Zone. 7.4% of the flights occurred within Authorization Zones and 6.3% of sUAS flights occurred within Restricted Zones. Researchers only detected two drone flights (1.0%) that couldn’t take off because of DJI geofencing restrictions.

Keep in mind, Embry-Riddle was using DJI’s propriety AeroScope that only detects DJI products. This means researchers probably only detected about 70% of drone flights in the area given DJI’s share of the drone market.

Addressing the problem

What is our country doing about this problem? Not much that I can see since the conclusion of the FAA’s Aviation Rulemaking Committee on Remote ID last September. The ARC report was contentious because the commercial drone lobby clashed with consumer drone manufacturers and modellers over which types of drones would require remote ID. The FAA put in a performance-based standard against opposition from the commercial drone lobby that wanted a weight or payload-based standard. The performance-based standard left a giant loophole for hobbyists because at the time, the FAA could not regulate model aircraft and, hence, drones flown by hobbyists.

The FAA doesn’t have that excuse any more. As I mentioned in the last issue, the 2018 FAA Reauthorization Act allows the FAA to regulate hobbyist drones, specifically allowing the FAA to mandate equipage for safety/NAS integration, remote ID and procedures on avoiding risks to aviation safety or critical infrastructure. If that wasn’t enough, Congress goes further and tells the FAA to start a five-year remote ID pilot program.

Granted, the FAA has only had this guidance for about a month and it’s unfair to expect them to set up a pilot program in a month. But they’ve known remote ID is an issue for years and haven’t started a major research program yet. The 13 days in May study was self-funded even though the Embry-Riddle is a lead ASSURE FAA Unmanned Research Center of Excellence university. The only research I’ve seen is a year old MITRE research paper on using ADS-B for drone navigation and an ASSURE research project by North Carolina State on the advisability of using ADS-B as a drone sense and avoid technology. The MITRE paper had no field research to back up its findings and the ASSURE study didn’t address remote ID.

Developing the technology

Remote ID will require some challenging technology. The FAA should have been researching the various technical solutions while waiting for Congress to decide policy issues with remote ID, yet neither ASSURE or the UAS Test Sites have gotten any FAA research funding for remote ID. Many expert observers think the best answer is to use ADS-B for drone remote ID. However, MITRE’s theoretical study showed drone traffic would saturate ADS-B frequencies if drones broadcast ADS-B at the same power as manned aircraft. MITRE concluded that low powered ADS-B remote ID might work, but the FAA never funded field research to test this theory. The cell phone industry is aggressively pushing LTE for remote ID, but they have only done internal, propriety research so far. Remote ID experts have doubts that LTE remote ID will work outside cell phone tower coverage and even within coverage, LTE antennas are pointed down to enhance surface cellular connections, not up to cover drones. DJI is attempting to gain market share by selling its AeroScope remote ID system, but this is a propriety system that will only work with DJI products. A great compromise system would be to avoid frequency saturation by using the ADS-B waveform but broadcast it on an alternate frequency to the ADS-B spectrum. Only industry has researched this option and their results are propriety.

Time for Research

I know the FAA isn’t used to doing a tremendous amount of research before making a move like the Department of Defense and NASA does. However, given the technical challenges they’re facing with remote ID they really should get ASSURE, the test sites and the FAA Tech Center proactively researching the technology behind remote ID. Setting counter UAS operations aside, remote ID is the key to everything beyond the basic Part 107 rules. Operations over people is difficult without remote ID. Beyond line of sight operations and unmanned traffic management are nearly impossible without remote ID. From a counter UAS perspective, I think13 days in May over Daytona Beach proved our nation is at risk from clueless and careless remote pilots. Let’s hope we don’t see more criminal drones before we have remote ID.