Ukraine launched its long-awaited counteroffensive this summer, but Russian drones and artillery have slowed it down, forcing a change in tactics.

The terrible war triggered by Russia’s botched full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 entered a new phase this summer when Ukraine unleashed its long-awaited counteroffensive, bolstered by freshly created brigades, some equipped with powerful Western armored vehicles.

The offensive had two major axes in southern Ukraine, lunging from Orikhiv toward Tokmak and Melitopol, while Ukraine’s Marine Corps advanced down the Mokra Yali river toward Staromlynivka and Mariupol. A tertiary eastern effort focused on recapturing the flanks around the city of Bakhmut.

But high hopes were shattered on impacting the Surovikin line, multiple belts of Russian fortifications and dense minefields constructed in southern Ukraine line. The culprit? The very teaming of drones and artillery from which Ukraine itself had long profited.

On June 6, Ukraine’s 47th and 33rd Brigades, equipped with Bradley fighting vehicles and Leopard 2A6 tanks, attempted to breach Russian minefields near Mala Tomachka, spearheaded by mine-plow tanks. But three Russian Orlan-10 drones surveilled the attack and summoned accurate artillery fires, kamikaze drones and missile-armed attack helicopters, disabling the mine-clearing tanks. Subsequently, more vehicles were disabled by mines attempting to bypass the knocked-out breachers.

The battle revealed that drone intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, wedded to effective precision fires, could render the mechanized breaching tactics developed in World War II insupportably costly. Massed armor was simply too easy to detect and rapidly strike.

Ukraine quickly abandoned mechanized assault tactics and reverted to a World War I-like battle of attrition with infantry and engineers slowly securing ground. Meanwhile, its artillery, enjoying ammunition superiority for the first time, methodically mauled enemy batteries and fortifications, bolstered by the United States’ release of cluster artillery shells to Ukraine. It appears Ukraine had introduced new technology and techniques to sharply reduce drone losses to Russian jamming, enabling more extensive use of drone-directed precision fires.

Still, Russia’s aggressive forward defenses, though costly, made territorial gains slow and limited—perhaps 800-1,300 meters every five days, according to a study by the British RUSI think tank. Finally, in August and September freshly committed brigades managed to capture Robotyne and breach the Surovikin line’s first layer. Kyiv appears intent on sustaining the counteroffensive through fall in hopes of exploiting the widening breach, but whether it can attain the key objective of Tokmak is uncertain.

THE LAYERS OF THE UKRAINE DRONE WAR

‘Infantry’ Drones

At the squad, platoon and company level, infantry and armor units in Ukraine make extensive use of small, civilian quadcopter-style drones. Ukrainians and Russians alike see them as indispensable for command and control and situational awareness, even though their allocation isn’t standardized in army organization charts. Thus, a unit’s ability to fundraise on social media and connect with volunteer or government-led donation programs can heavily impact their effectiveness.

Civilian quadcopters can be easily converted into strike platforms by mounting grenades or (if a vehicle is larger) mortar shells or anti-tank mines, lethal against both soldiers and armored vehicles. Ukrainians are cutting open recently donated 155mm cluster shells to recover the anti-tank bomblets for use by drones.

Ukrainian troops have complained that NATO training, which calls for commanding officers to lead from the front (where their vision is limited and they are at risk of getting killed), is misguided. They prefer commanders to stay back and use drones to obtain better situational awareness across the unit’s entire front, and quickly issue orders to subunits in response to tactical developments. Tank company commanders too are eschewing command tanks to observe battles from above by drone, spotting concealed enemy infantry and anti-tank weapons, and directing main gun fire toward them.

Brigade and Battalion Drones

Ukrainian and Russian infantry, armor and artillery brigades/regiments use catapult-launched, fixed-wing drones for longer-range reconnaissance and fires direction or attacks with kamikaze drones. Such unarmed ISR drones have a terrifying capacity to influence the battlefield by acquiring targets for annihilation by artillery. Drone-directed strikes using guided howitzer shell GPS-guided Excalibur, laser-guided Krasnopol and Volcano rounds, and SMArT 155 and BONUS radar-guided anti-tank submunition rounds can reliably destroy valuable armor, artillery and air defenses, as can M31 GMLRS fired by HIMARS and M270 rocket launchers.

Ukrainian brigades (and some elite battalions) also field organic drone-strike companies—their “in-house” air support. Formerly, these involved larger grenade-dropping vertical-lift UAS (such as the 270 Kazhan heavy bombers recently ordered), but increasingly rely on first-person view (FPV) drones instead.

Of course, ISR recon remains the main role for drones in Ukraine.

Samuel Bendett, Russian drone expert, Center for New American Security

I don’t think we have reached the ceiling of sophistication.”

Operational and Strategic Reconnaissance

More sophisticated and longer-range drones, or both, have become the purview of elite special operations and drone specialist units controlled by regional commands or GHQ, as well as intelligence services like Ukraine’s HUR and SBU. Some such units specialize in precision strikes against high value targets like artillery, armored vehicles and rear area depots.

Drone ISR: Room for Improvement

Drones that can fly further and still perform their mission in an environment replete with radio and satellite navigation jamming are at a premium in Ukraine. At Russia’s Dronnitsa conference, one lecturer remarked that friendly fire losses to electronic warfare and air defense often exceeded those inflicted by Ukraine, showing a need for better deconfliction.

“Of course, ISR recon remains the main role for drones in Ukraine. I don’t think we have reached the ceiling of sophistication,” Samuel Bendett, an expert on Russian drones and AI research at the Center for New American Security, told Inside Unmanned Systems. “There’s the imperative to extend the range from five to 12 kilometers to 20 to 25 kilometers. Some of these will be aircraft-type drones, not just quadcopters. They don’t have to be perfect, they have to do the job and don’t need to cost a lot of money.”

Indeed, Russian drone volunteers lament that Russia’s military industry fails to appreciate that high-cost drones are lost in combat at a rate disproportionate to their price. Builders and operators need to internalize that tactical UAS are expendable items with limited odds of survival, they say.

Deadly duo: Lancet and Orlan

The Orlan-series of ISR drones and Lancet kamikaze drones have become load-bearing structures for a Russian military otherwise lacking ability to conduct time-sensitive deep precision fires in response to Ukraine’s long-range artillery.

The much-in-demand STC Orlan-10 is a key method by which Russia locates valuable enemy assets and summons artillery or kamikaze drone strikes to destroy them. Losses of Orlans are heavy—186 of all models by early October—and recovered wreckages show low-quality production shortcuts, such as plastic water bottles used as fuel tanks. However, Russia’s defense minister Shoigu claimed in July that production of new Orlan-10s and -30s (which cost $87,000-$120,000 each) has multiplied to 53 times the pre-war rate.

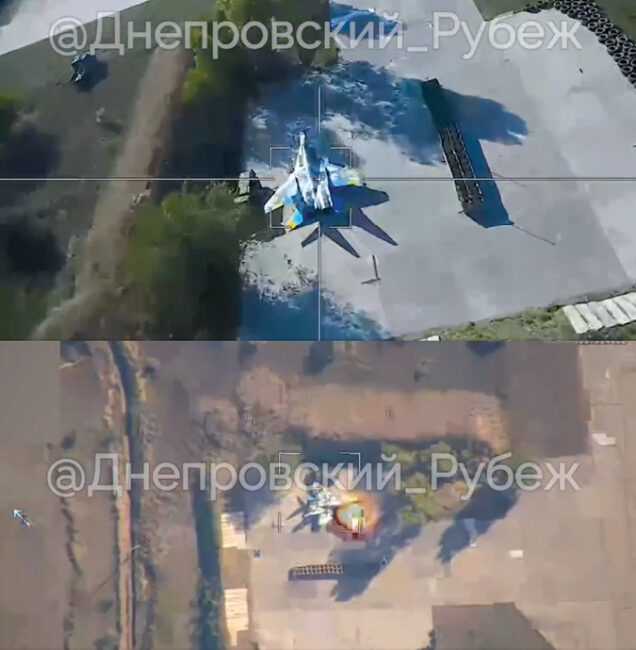

Russia’s preferred counterbattery weapon responsible for most kills of advanced Western-supplied artillery aren’t its own batteries, but Lancet-3 kamikaze drones. Furthermore, one Lancet-3 somehow traversed 50 miles to damage a Ukrainian MiG-29 fighter at Dolgintsevo airbase with a very near miss—results Russian cruise missile strikes have been unable to attain for months. Meanwhile, FPV drones handle shorter-range strikes, and laser-guided Krasnopol artillery rounds are also highly effective when laser-equipped Orlan-30 drones are available.

A Kalashnikov ZALA-421-16E, a short-range alternative to Russia’s Orlan drones, at a 2013 exhibition.

Photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and Vitaly Kuzin/Wikipedia.

FPV Wars Episode 2: Russia Strikes Back

A year ago, only early hints of the FPV racing drone’s battlefield importance were emerging. Now, they’re at the forefront of Ukraine and Russia’s cheap-tech arms race—despite production being almost entirely driven by volunteers, non-profits and small startups nonetheless proven capable of mass-producing thousands of FPV drones monthly. Ukrainian forces are asking for 30,000 FPV drones a month.

“What has happened is a move away from expensive platforms like Bayraktar or Orion [large combat drones], and more toward kamikaze drones,” the Center for New American Security’s Bendett said. “There are also designs for dive-bomber DIY drones. That’s a more difficult pull, but it’s not impossible.”

A Quantum Systems Vector drone, donated to Ukraine.

FPV drones serve as the poor man’s Hellfire missile or Joint Direct Attack Munition, democratizing the precision air strike. Even a $6,000 Switchblade-300 loitering munition, built for a similar mission but with greater automation, costs an order of magnitude more than FPV drones. They’re typically priced at $350-450 and sometimes made of plywood.

Yes, FPVs are slower than a Hellfire, with a fraction of the explosive payload. And a Ukrainian pilot told The New York Times that less than a third of FPV attacks are successful due to jamming, short endurance and pilot error. But they’re precise enough (in the hands of a skilled operator) to glide into slit trenches or through windows to kill individual soldiers, or to disable or destroy vehicles potentially worth millions of dollars. One Ukrainian FPV pilot profiled by The Guardian was credited with destroying five tanks, five APCs and two infantry fighting vehicles without risking valuable combat aircraft.

The Sypaq Corvo Precision Payload Delivery System is made of waxed cardboard, giving it a low radar cross-section and reduced weight.

A Ukrainian officer told The Washington Post that FPV drones have become “the main anti-tank weapon.” The same article describes the 47 Brigade’s drone strike company assembling FPVs and expending 20 daily. Operators reportedly use more jam-resistant analogue videofeeds instead of digital ones, and occasionally accidentally intercept feeds from enemy drones. Quadcopter repeater drones are used by both sides to extend effective control range.

Videos of FPV strikes often reveal high degrees of operator skill, as the drones perform rotating maneuvers to identify the best angle to approach soldiers concealed in trenches or dugouts or intercept moving vehicles, executing sharp last-minute rolls and hairpin turns. In one incident, an FPV operator nearly rammed a Russian Ka-52 attack helicopter from the side, but fell behind the faster aircraft.

A UKRSPECSYSTEMS Shark drone, with a maximum range of 186 miles.

Ground vehicles and artillery increasingly bulk up on passive defenses against FPVs, including drone-snagging nets, wire fences and top-mounted “cope cages.” Startlingly, the Sudanese army also recorded its use of Ukrainian-style FPV drones to accurately strike troop trucks of the rival RSF faction in Khartoum, which has ties to Russia’s Wagner mercenaries. Some media reports suggest these drones and their operators were Ukrainian.

THE DRONE INDUSTRIAL WAR

Recently, Ukrainian sources despaired that Russia has pulled ahead in deploying FPV drones, with one Ukrainian pilot claiming in an August interview that Russia is using 40,000 FPV drones a month.

But Bendett cautioned such despair needs to be seen in context. “Both sides are using the same language to talk about the other side’s perceived advantage in FPV drones and electronic warfare systems,” he said. For example, a Russian drone operator bemoaned on Telegram that Ukraine is overwhelming them with 20,000 FPVs produced monthly.

“It’s all about where you are, what kind of unit you are, what kind of countermeasures are arrayed against you,” he said. “What has happened in the last six months is Russian volunteers have scaled up large-scale FPV manufacturing. And they’re claiming many thousands are being built monthly.”

By Bendett’s calculations, the most optimistic claimed figures for Russian FPV production total 20,000 to 25,000 monthly, but are “probably smaller” due to lack of coordination and cooperation between volunteers and industry (which accounts for 6,000 FPVs monthly at best.)

It’s not that Kyiv isn’t investing, having recently devoted $1 billion to drone manufacturing. But some Ukrainians are disappointed drone manufacturing hasn’t scaled up production of “national champion” UAVs as some wish.

In Ukraine, the Army of Drones initiative led by Innovation Minister Mykhailo Fedorov has led to the introduction of more than 40 types of drones, up from seven, with a pivot from pure ISR focus to diverse combat roles.

“Fedorov and Ukraine’s Ministry of Defense publicly speak about their support to demonstrate the government is open to cooperation, supports private efforts, and will certify a lot of drones,” Bendett said. “Obviously, this is great, but will there be selection [of ‘champion’ products] or will this be more Chinese-style ‘let a thousand flowers bloom?’

“Both sides have an uneasy relationship between legacy industrial drone projects and new startups that are much faster and can adapt to new problems,” he said. “Things are a bit smoother on the Ukrainian side, but we’re learning from [Defense Minister] Reznikov’s departure there remain issues. Despite Fedorov doing a wonderful job, there are still not enough drones nor industrial capacity for FPV drones.

What has happened is a move away from expensive platforms like Bayraktar or Orion [large combat drones], and more toward kamikaze drones.”

Samuel Bendett, Russian drone expert, Center for New American Security

“The Russian approach is more conservative, they have to support their pre-existing defense-industrial complex. There’s a question to what extent they will continue tolerating private sector technologies subsuming their field and allow them to remain semi-independent,” he said. One issue is Russian military-grade substitutes for cheap civilian systems are worse in every way. “Russian military quadcopters cost a lot more than volunteer built FPV drones and are worse quality,” particularly Dobryna, an expensive but inferior knockoff of a DJI quadcopter.

Russian companies and NGOs don’t lack for innovative ideas: There are concepts for “sleeper” drones planted to ambush enemy forces, use of neural networking-AI for target classification to enable lock-on guidance, anti-helicopter FPV drones, and drone carriers hefting multiple FPV drones. However, Russia’s industry-to-production pipeline remains ponderous, and innovation is mostly driven by motivated volunteers.

War at the Mercy of Commerce

Both sides heavily depend on foreign companies for drones and drone parts. That means their access to these is subject to the whims of those companies and their government regulators—particularly China, with DJI holding 90% market share of the global consumer drone market.

Ukrainians worry Beijing could throw in fully for Russia and disable Ukrainian-operated drones remotely through software patch updates, safety software and geofencing systems. Furthermore, on Sept. 1, China enacted new legislation restricting drone part exports, a move corresponding to a throttling down of Ukrainian imports. Meanwhile, a recent video by two Russian drone-supplying volunteers shows them brazenly arranging a large drone purchase with Chinese drone-manufacturer Autel.

But a broader change in Chinese policy doesn’t appear imminent, Bendett said. “[Export restrictions] will hike up prices on existing drones and components. But people can still buy components to build low-level drones by the box. Those volunteers, they know how to get the stuff. Market forces will find a way.” Nonetheless, Ukraine’s fears highlight how Western manufacturers are far from being able to substitute for Chinese consumer drones in terms of price efficiency and volume.

Ukrainian drones also depend on the Starlink satellite network to resist Russian jamming and strike deeper into Russian territory—initially donated by Elon Musk in 2022. But that fall, Musk geofenced Starlink access on the Black Sea after consulting with Russian contacts who claimed (wrongly) that Ukrainian attacks on Crimea would cross a red line. As a result, Ukraine lost control of kamikaze boats enroute to attack Russian warships in Sevastopol last September. Starlink access is now funded by the U.S. government.

STRATEGIC DRONING: RUSSIA AND UKRAINE’S LONG-RANGE STRIKES

Far behind the trenches, a strategic drone war rages dominated by drones and cruise missiles. By the summer, Russia’s daily broadsides directed at Ukrainian cities was being met by an asymmetric Ukrainian campaign of drone attacks on land and at sea—more limited in volume, but more effective against military targets.

The clearest effect has been to force both Russia and Ukraine to retain and spread out substantial air defense assets to guard the home front at the expense of frontline units and rear-area military bases.

It remains to be seen whether either side’s strategic droning campaigns will achieve the hoped-for effects of decreasing the public’s support for the war effort or causing major economic damage.

Russia’s strategic droning has fallen into a rhythm, with a wave of a dozen or so Iranian-exported Shahed-136 long-range kamikaze drones daily vectored in on Ukrainian cities, sometimes simultaneously alongside subsonic or supersonic cruise missiles. Ukrainian air defenses routinely down around 75% of the Shaheds—or even 100%—but those that get through still occasionally cause massive damage and kill civilians.

Beyond serving as random terror weapons and penetration aids for punchier (and vastly pricier) cruise missile, by late summer Shaheds had success economically damaging Ukrainian port facilities and grain stores in Odesa and along the Danube river, including Reni and Izmail.

As Shaheds cost just $20,000-$50,000 apiece, these modest results are deemed acceptable because they serve Moscow’s longer-term strategy of exhausting Ukraine’s surface-to-air missiles. Most of Ukraine’s older Soviet SAMs simply can’t be replaced. And every half-million-dollar AMRAAM and IRIS-T missile, or multi-million-dollar Patriot used to down a Shahed is an economically favorable exchange for Russia. Ukraine clearly prefers to assign Shahed-killing to short-range missile teams and self-propelled anti-aircraft guns (Gepards or improvised gun trucks). How many more capable air defense missiles are still expended stopping Shaheds remains understandably unclear.

Russia’s Shahed campaign, however, has its own sustainability hurdles to jump, having already consumed most of the 2,400 Shahed-136s and -131s ordered from Iran last fall. But Russia’s $2 billion deal also involved a tech transfer intended to result in local production.

By August, the Conflict Armament Research group confirmed that Russia had begun assembling Shaheds in Russia from kits delivered by Iran, but with several newly Russia-sourced components: fiberglass and carbon fiber insulation, the 60-gram Kometa jam-resistant GNSS satellite navigation system (also used in Orlan-10 and Forpost drones), flight control, inertial measurement and starter units.

An abandoned factory in the depressed Tatar-majority Alabuga region of Russia was refurbished for production of “boats.” By August, it was assembling (not building) 70 Shaheds monthly. Russian human rights investigators revealed the factory relies on high school teenagers from a local technical college forced to take on 12-hour-a-day “internships” at the factory, or face expulsion and payment of massive fines. This coerced labor is supplemented by African and Central Asian girls recruited via dating apps. The factory is supposed to deliver 6,000 drones by September 2025, the later two-thirds built mostly locally.

Starting with its May attack on the Kremlin, Kyiv has dramatically scaled up strategic strikes on targets in Russian soil.

Ukraine’s lower volume attacks cause few if any deaths but create spectacle in the Russian capital or places like Smolensk and Sochi, disrupt flights at international airports, and appear more precisely targeted at state institutions and factories (including those manufacturing microelectronics for Iskander and Kh-59 land-attack missiles and air defense systems).

There’s little evidence they’re affecting Russian popular support for Putin’s war, but they may negatively affect elite opinion by demonstrating Putin’s inability to secure Russian airspace. More tangibly, the strikes compelled the Kremlin to withdraw frontline and base short-range air defenses (particularly Pantsir-S systems) to defend Moscow and other urban areas.

Long-range drones developed in Ukraine that Kyiv can launch from its territory in a manner similar to Shahed drones conduct some of the attacks. Notable examples include the Bober and UJ-22 drones, as well as a new, unnamed type armed with a K3-6 shaped charge warhead.

But some of Kyiv’s most effective attacks involve a different method: Infiltrating agents with short-range drones into Russian soil who assemble, launch and remotely control drones to execute precision attacks on Russian military bases.

In August, Ukrainian kamikaze quadcopters destroyed a Tu-22M3 supersonic bomber at Soltsy-2 near Novogorod, compelling its unit to redeploy 800 miles away. Then on Aug. 29, another attack by 22 civilian quadcopters inflicted massive damage to Princess Olga Pskov international airport (400 miles north of Ukraine), destroying or crippling four large Il-76 cargo jets.