Created to work toward establishing rules for BVLOS operations for UAS, the FAA BEYOND program is doing work that helps move us closer to a more fully autonomous UAS airspace.

The genesis of BEYOND goes back to 2017. At that time, a Presidential memo established the Unmanned Aircraft System Integration Pilot Program (IPP), which brought nine airfield testing sites into a collaborative association to address challenges in the emerging UAS environment.

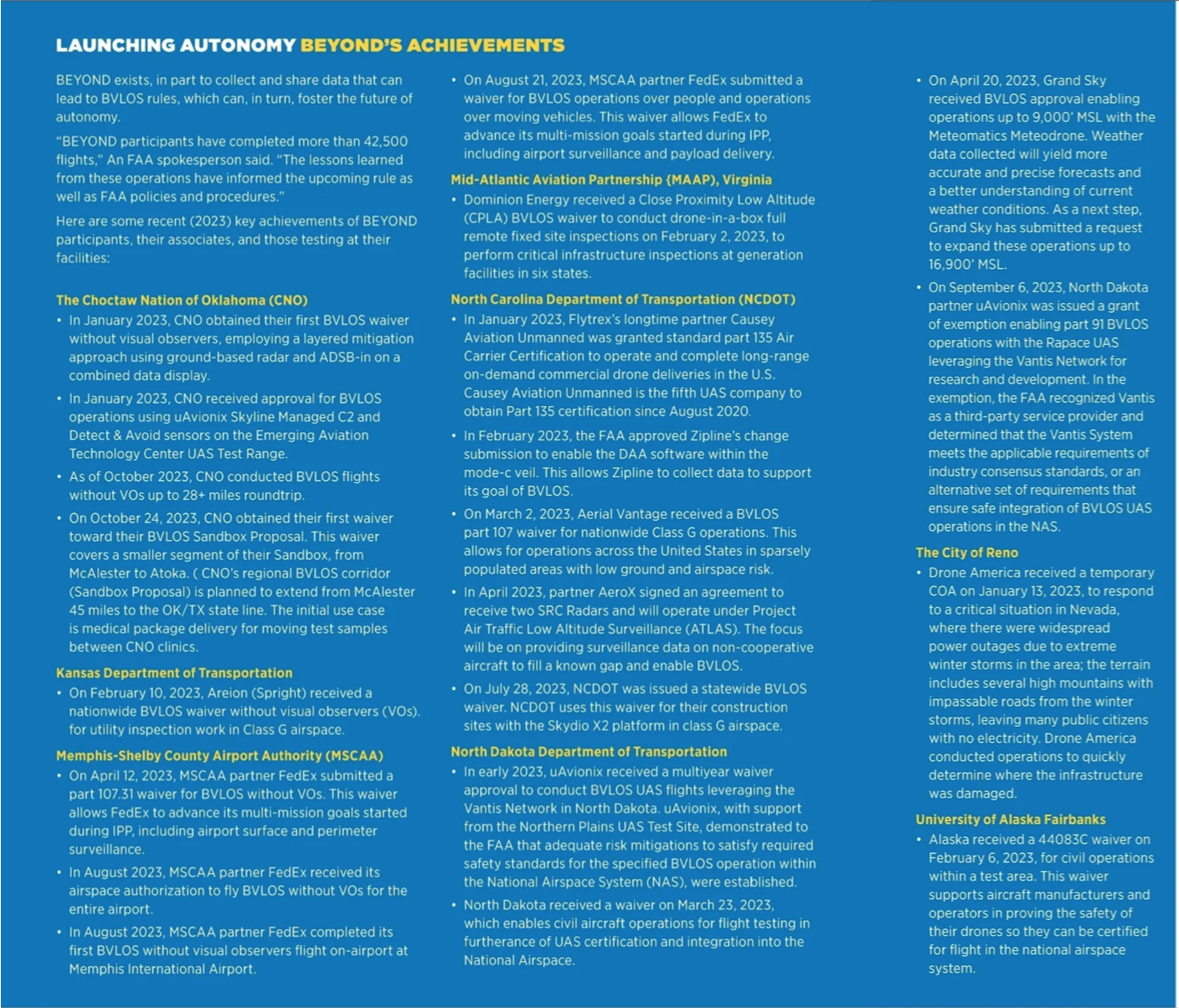

When IPP ended in 2020, the FAA established a four-year successor program—BEYOND—to continue partnerships and progress for the eight remaining sites (after San Diego dropped out) and address remaining challenges. BEYOND’s focus was to collect data, address community feedback, more fully understand the potential of drone use and work toward a rule based BVLOS environment rather than one of continual waivers. Most of the BEYOND accomplishments to date, however, are an assortment of waivers that provide the data to eventually reach this goal.

Inside Unmanned Systems announced the BEYOND creation in October of 2020 and in December of that year as part of the future of test and evaluation systems.

WORKING TOGETHER

A key component of the program is sharing data between the eight sites and between them and the FAA. They have regular virtual and in-person gatherings and see this communication channel as well as easy access to and ongoing communication with the FAA as key advantages.

SPECIALTIES AND CHALLENGES

The BEYOND participants are state, local, tribal, and territorial entities. Typically, they focus on a use case or cases as well as other unique capabilities and may involve challenges specific to their own missions. Here is an overview of what’s happening across the test sites.

Virginia Tech MAAP— “Our three use cases,” said Tombo Jones, director, Mid-Atlantic Aviation Partnership (MAAP) at the Virginia Tech FAA designated UAS test site, “are public safety, package delivery, and linear infrastructure with regard to power companies. From the beginning, our partners have been [Mountain View, California based] Wing, which is a package delivery company, and [Richmond, Virginia based] Dominion Energy. “One of the main things that we test and evaluate is detect and avoid systems. And we have the only FAA approved test method for evaluating an aircraft’s ability to comply with an “operation- over-people rule.” They test very lightweight drones against a car crash dummy, he said.

Jones said the actual FAA BEYOND arrangement is with the Virginia Innovation Partnership Corporation (VIPC), which connects entrepreneurs with opportunities in the commonwealth and contracts with the test site and MAAP.

Alaska—Alaska focuses on issues unique to Alaska, such as flights over pipelines and medical supply delivery, said Catherine Cahill, director the Alaska Center for Unmanned Aircraft Systems Integration (ACUASI). “Aviation is the lifeblood of Alaska. We’re an aviation state. We want to be a leader in serving our communities.”

“IPP and BEYOND were originally designed for (flying) under 400 feet”, she said. “If you’re going long distances with the terrain we have. it’s actually easier and safer for us to go higher. So, we’re focusing right now on long linear infrastructure, mainly the trans-Alaska pipeline.”

A challenge, she said, is drones in Alaska fly in areas that, for the most part, are GPS denied. “The communications are bad and the navigation is challenging. In addition, we have a lot of general aviation that is non-transponder. So, we have a major safety case even with small UAS.” She said many general aviation pilots don’t use transponders because they don’t want people to know where their hunting spots are, or where they might be poaching, or to avoid landing fees. “It’s an Alaska thing,” she said. In Alaska, planes aren’t required to be equipped below 10,000 feet.

“IPP and BEYOND have let us work on our detect and avoid issues. Working on BVLOS and communications with BEYOND has been incredibly helpful for us.”

ACUASI also works on food, medicine and staples (such as diapers) delivery to remote communities. “We don’t have a last mile problem; we have a hundreds of miles problem,” Cahill said. “Eighty-two percent of the communities in Alaska are only reachable year-round by air.”

ACUASI is also working on type certifying a few aircraft, she said.

Alaska is also a bit different from the other BEYOND members, as they use test ranges in 14 other states in addition to their site in Alaska.

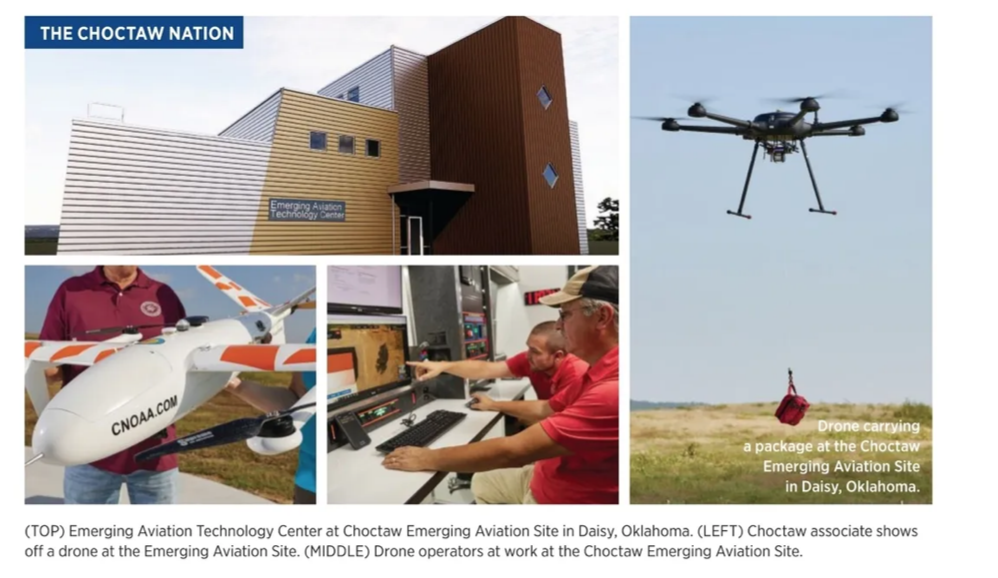

The Choctaw Nation—The Choctaw facility is part of the reservation in Oklahoma near the Texas border. James Grimsley, executive director of the Advanced Technology Initiatives of the Choctaw Nation said they are focused on rural applications such as health care. “We’re building out quite a bit of infrastructure, a very sophisticated aviation test range here, as well as an electronics fabrication facility and hangars. We have a separate fabrication facility for drones.”

While they have a hospital and clinics, as well as pharmacies, they want to use drones because the roads between facilities are very bad. “Our big challenge and our focus right now is infrastructure, which we need for widescale BVLOS flights.’

Grimsley notes they have a separate fabrication facility where they build drones. They are building permanent infrastructure, even including an RV park for people who come to test there. Their largest BVLOS waiver to date has been for 42 miles. They are building out their own Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B) receiver network across the reservation. “We basically monitor aircraft, both with our radar and ADS-B,” he said. “Our operations and towers are very dense.”

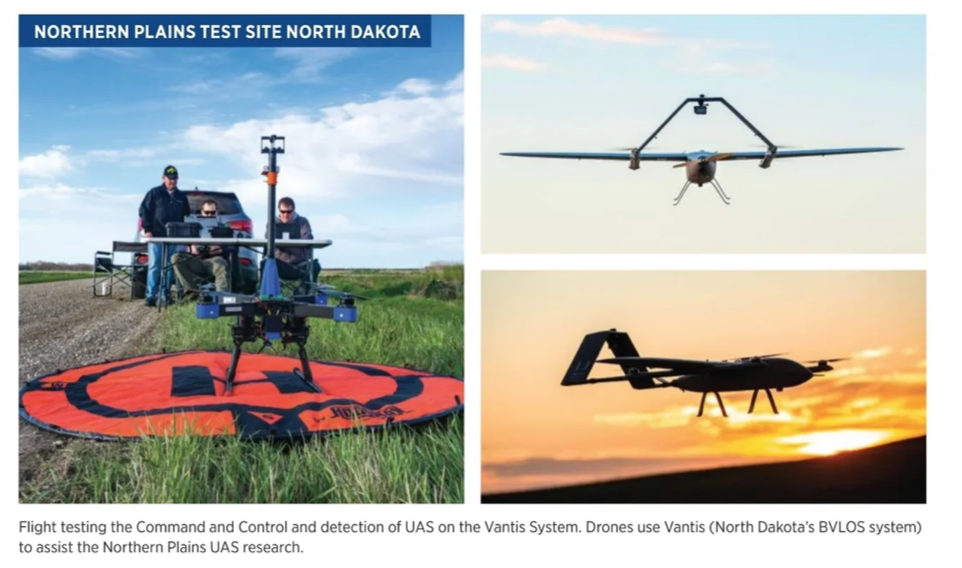

Northern Plains test site North Dakota—“We’re less focused on specific use cases and more on the underlying safety component,” said Trevor Woods, executive director of the Northern Plains UAS Test Site in North Dakota, which is operated for BEYOND by the North Dakota Department of Transportation.

“We work through various FAA partnerships,” Woods said. “We have quite a portfolio of things we’re working on, and so I use these programs [such as BEYOND] to ensure that we have that partnership with the FAA, that ability to pick up the phone and work through these complex issues regulatory and safety standpoints to be sure we’re not introducing unnecessary risk in the airspace system.”

“At the end of the day we don’t get any special privileges that allow us to get through the regulatory process faster, but it does let me have that trusted relationship. We essentially have an agreement that we’re going to work together. For example, some people may be nervous about what they’re telling the regulator, but I don’t think we have any of that with this relationship.”

Virginia Tech—“One of the main things that we test and evaluate is detect and avoid systems that are designed to see other aircraft and communicate the location of that aircraft,” said Tombo Jones, director MAAP at the Virginia Tech FAA designated UAS test site.

“Sometimes these are autonomous although sometimes they go to a display for the pilot. We’ve become experts in getting the waivers and exemptions to do the weird stuff, such as flying beyond visual line of sight with two aircraft simultaneously, with detect and avoid systems and manned aircraft intruders to test the detect and avoid, which is not a normal mission that someone would do.”

Jones echoed Alaska’s Cahill’s concern, pointing to rule making activity based on BEYOND and other data. “The way the rule is being written says that the drone has to give way to anyone with a transponder. But if an aircraft is lower than 500 feet without a transponder it could risk a collision with a drone. The FAA hasn’t made a decision yet but that will affect our industry a lot,” he said.

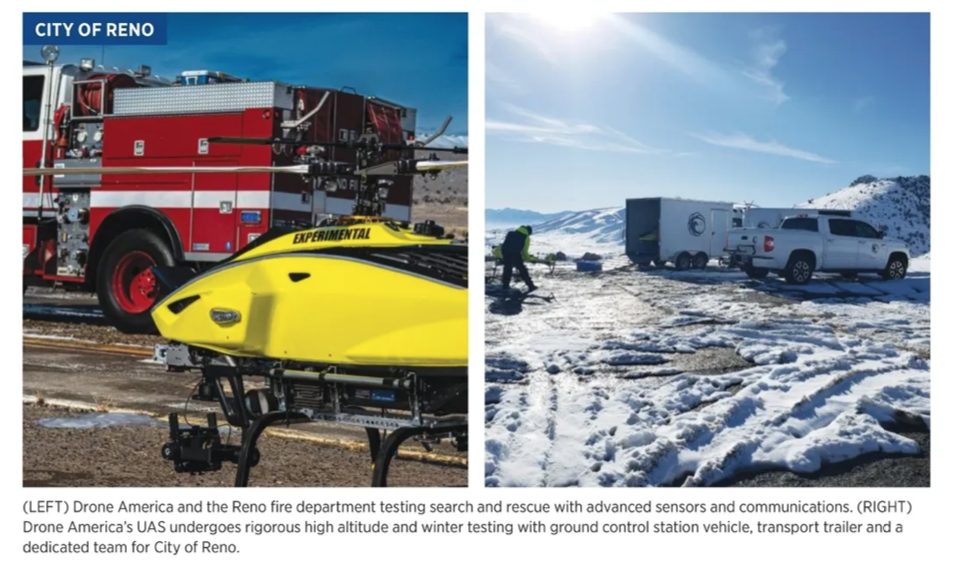

City of Reno—The city of Reno collaborates with Reno based Drone America. The company’s President Mike Richards said they’re working toward enhancing public safety through innovative UAS technologies. “These innovations elevate beyond mere tools, serving crucial roles in Search and Rescue (SAR) and Wildland Firefighting,” he said.

ON THE WAY TO AUTONOMY

BVLOS and autonomy are obviously not synonymous and autonomy is not necessarily a requirement for BVLOS. However, much of the data collected by BEYOND is relevant to autonomy efforts. The various members of BEYOND each take their own path to autonomy and they each have their own interpretation of what that means and the relationship to BVLOS.

“For Alaska, what we want is fully autonomous flight between our remote communities carrying hundreds of pounds of cargo,” Cahill said. “We have a need which is to protect human life. Right now, Alaska has one of the highest pilot fatality rates in the country.” She added, “Autonomous UAS could take the place of those manned flights.”

“We’re pretty far on autonomy,” Grimsley said. They are hoping to see improvements in onboard because they currently use mostly ground-based detect and avoid. “Onboard is the only way I believe we can really scale across big areas,” he said. “At some point, it becomes prohibitive to build ground-based radar everywhere.”

“Right now, we still need more data to make long term decisions on what the best scalable solutions are. So, we have layers of safety mitigations and we might not need them all in the future. Now, while the drones are on automated missions, there is an airspace observer who can step in if needed.”

“We want to start doing some trial missions between two cities that are both on a major freight corridor along highway 69. We have one fixed long range 2D Doppler shift radar that gives us about an 18 nautical mile radius of detection. And we’re putting in a second layer that will overlap this—a pretty sophisticated phased array of 3D radar. We have our own ADS-B receiver network that we’re building out across the reservation as well. Since we’ve built our own and have a density of these receivers, we can get very low altitude aircraft. So, we’ve just eliminated some of the low altitude concerns you have with ADS-B. We can watch aircraft all the way down to DFW [Dallas-Fort Worth]airport. That’s how robust our system is right now.”

“I’m happy to see that we’re making more progress in infrastructure and less on the aircraft,” North Dakota’s Woods said. “The automobile didn’t really prosper until we had a robust road network and what’s been lacking on the UAS arena is robust infrastructure, including traffic management, that let’s you know that aircraft is part of a bigger system and that let’s you know if two of us are going from point A to point B at the same time.”

“We’re developing a program called Vantis, a statewide network enabling UAS flights beyond visual line of sight. It’s a combination of ground and airborne surveillance, robust communications systems, and the critical piece, an operations center that allows tracking and monitoring on a real time basis to a performance metric that is acceptable to the FAA.’

The Vantis Mission Network & Operations Center (MNOC) is housed at Grand Sky at Grand Forks Air Force Base.

As to autonomy, Woods is less certain. “I recognize we have a lot of things to overcome, although I think Vantis is going to help,” he said.

ISSUES AND CHALLENGES

“A lot of the major issues are technological, Cahill said. “At our recent meeting [of BEYOND participants], detect and avoid was an issue for everyone, especially on small unmanned aircraft, because you don’t have the ability to carry the weight for those systems and still carry a payload that will do something.”

Spectrum is another major issue, she added. “There are a lot of people who are trying to get access to spectrum and you want to make sure that aviation and unmanned aircraft are not left out. There’s a lot of work going into a relatively short-range frequency that might not work in all places. So, what happens if you have to do several hundred miles in a single flight? How do you manage spectrum over these issues?”

For Alaska in particular, there is also the challenge of GPS at a far northern latitude. “GPS satellites are at the equator. We’re way far north. So, our vertical positioning isn’t very good using GPS. We also have mountains, which block the satellite signal. So, we’re working on developing new kinds of sensors and new kinds of software to be able to work under the really weird conditions here.”

There are also public relations issues, she notes. The BEYOND teams have done a great job of working with communities and stakeholders and even general aviation, she said

“An issue for me, Woods said, is what’s in place for UAS autonomy at the present moment. “In aviation as a whole, if you’re going to develop software that runs on, say, the avionics of a manned aircraft, there are requirements that tell us what we need to do to prove that our software is safe for operational flight. We don’t have any of those for autonomy or AI. We also don’t have a standard and I don’t think we’re in a place to set a standard. We’re going to have to explore how the software and hardware systems work together, and set some boundaries. It’s a hot button and the next unknown.”

“The FAA has been clear from day one of IPP that they want this to be integrated into the national airspace,” Jones said. There are questions, though, he said such as “How do you create a detect and avoid system without transponders?”

“That’s why you saw them [the FAA] come out recently with the shielding rule where you can get permission to fly within 50 feet of a pipeline or power line. No aircraft would be that close because it’s too dangerous. Our concern is if we lose link.”

He also said another challenge is acceptance by the public. “It will take probably a decade at least for the public to trust driverless aircraft, but I think we’ll see a lot more autonomous drones operating within that decade,” he said.

TRENDS

“We’re all doing different things but we’re starting to trend, we’re all making similar progress,” said Choctaw’s Grimsley, “and as we do that, everyone starts to converge.”

North Dakota’s Woods sees a trend in the search for what diversity of sensors are needed to get to the solution. He sees radar as limited. “We might have some additional radars deployed out there, but we’re also seeing acoustic sensors that are listening for audio in the airspace system, and that can triangulate the location of aircraft or targets. We’re seeing optical sensors looking and scanning for traffic. I don’t think any of these are the silver bullet but they’ll serve a place, potentially. It’s the diversity of sensors being developed. And systems that let that work together—hardware, software and human.”

One really good trend said Virginia Tech’s Jones, is that the FAA is trending towards standards. That’s great news, first because there is a lot of work going into them and secondly, if there are FAA accepted standards it will speed up getting to more efficient operations.”

FROM WAIVER TO RULE

While documented successes from the BEYOND group to date involve waivers, these contribute to the database that will influence rules.

The big topic from the workshop (in March) from participants who were willing to share, was really the next phase of the program. It’s set to sunset in October but in the new FAA authorization there will be language to continue, they said. The takeaway was probably just the general thought on what do we want out of the next program. They pointed to tactical level discussions, such as how to manage the program, or how the FAA will provide resources to each team, or a program manager who will interface on a weekly basis. But for the most part, the emphasis was on what the next four or five years are going to look like with the FAA.

“And to be clear the point of the program isn’t necessarily about autonomy, says North Dakota’s Woods. “It’s really about BVLOS. Autonomy might be a piece of getting to that but it’s not the objective. I don’t think it’s the FAA objective.”

From the FAA’s perspective, “The purpose of [the recent] meeting was to hear from BEYOND program participants about lessons learned and challenges expected over the next four years. The FAA will use this information to develop future program objectives. The overarching theme that emerged was “bigger, longer, higher”—bigger drones, drones flying longer distances, and drones flying higher altitudes, the spokesperson said.

“Waivers allowed the FAA to collect flight data and identify and validate technology and safety procedures necessary for advanced airspace operations. Because the new rule is about normalizing drone flights beyond visual line of sight, the most important waivers are the BVLOS approvals. They represent the first steps toward routine, scalable BVLOS operations.”

Jones notes the BEYOND participants were part of the meetings to develop a BVLOS rule and much of the BEYOND work provided data. “We met for about nine months, including industry and FAA people. A great example of the BEYOND program recommendations as part of that ARC [aviation rulemaking committee] had to do with shielding,which comes about when a drone flies closer to a building or structure than an airplane can. We were able to get a waiver for 41 of their power generation sites. If drones remain within 100 feet of the structure, they can operate without actually seeing the drone.”

BEYOND LEGISLATION

This spring, both the House and Senate versions of the FAA reauthorization bills direct the agency to develop a UAV BVLOS notice of proposed rulemaking within 4-6 months of the legislation’s passage that will look to adopt a final rule within two years. The expectation is that a notice of proposed rulemaking will come out this summer.

In early March, Congress extended FAA authorization to May 10 to give Congress more time to finalize details for a final five-year reauthorization bill. Because most of the bills that aren’t in agreement are related to the airline industry, it’s likely the UAV BVLOS provisions will pass.

Woods said a lot of what they’ve done helped the FAA realize they needed to create the ARC to provide recommendations for the BVLOS rule. “I think you’re going to see a rule that comes out that says to meet BVLOS you need to meet these requirements.”

So, the BEYOND program is about BVLOS; but BVLOS and the road to autonomy are frequently intertwined.

“We are in the early stages of UAS autonomy, “FAA spokesperson said. “As with everything we do, safety will determine the timeline.”