Photo courtesy Kongsberg Geospatial

Challenges must be overcome to succeed in the commercial space, but companies have used their military backgrounds to their advantage.

Before the commercial drone market explosion of the last few years, drone companies focused on providing solutions to militaries all over the world. Manufacturers knew how to win defense contracts and what was expected of them when they did.

Many of these military-oriented companies are starting to move into the commercial and civil markets, leveraging their experiences and lessons learned as defense contractors. But, while there are plenty of opportunities and a variety of verticals are good fits for their solutions and know-how, going commercial isn’t exactly an easy transition. The commercial market represents a whole new ball game, with different players and expectations, and rules that are much less defined. Even so, some companies are finding success, whether by revamping military technology or by creating completely new systems that play well in commercial and civil spaces.

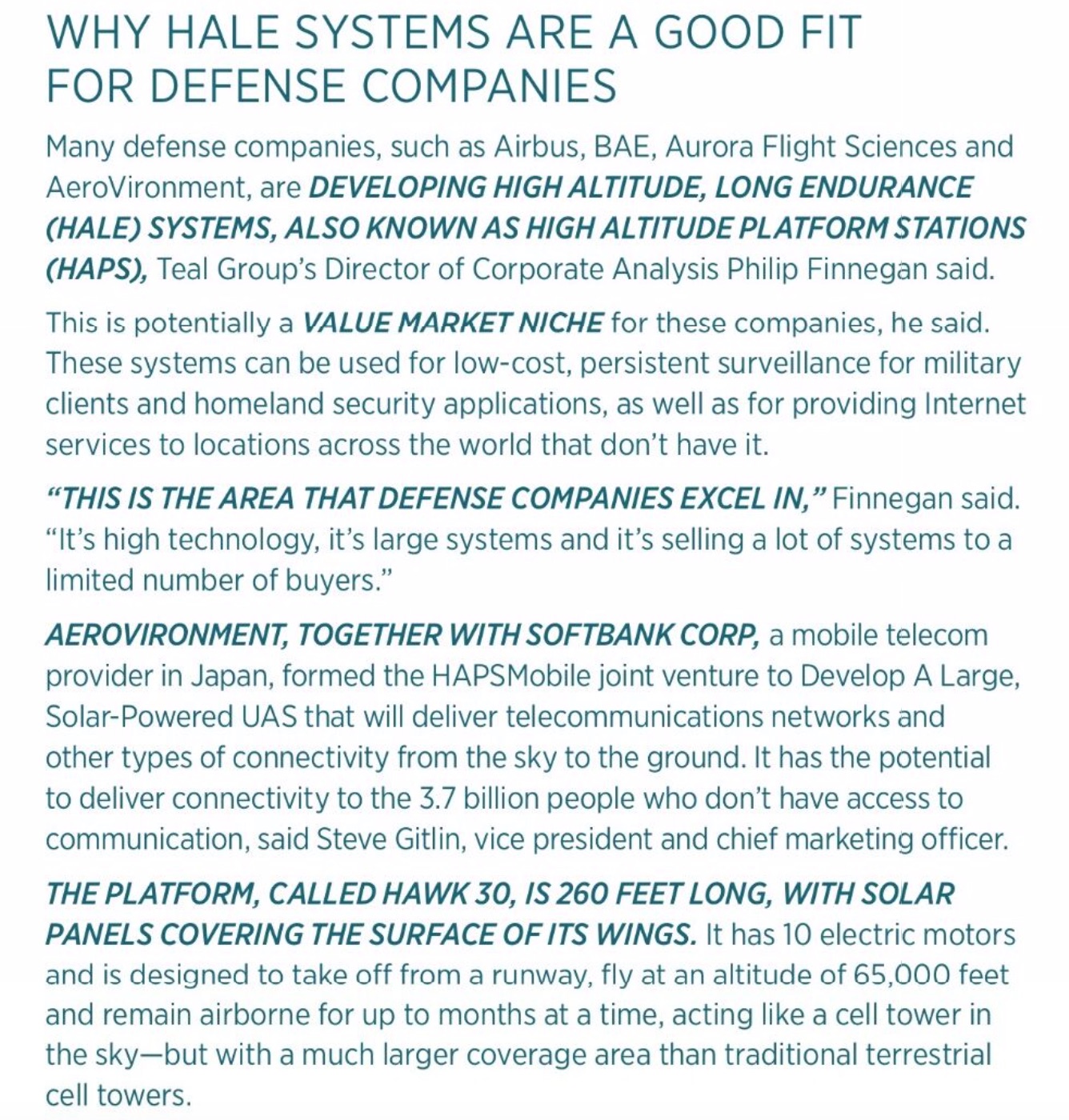

Defense companies tend to have more success in the civil market, Teal Group’s Director of Corporate Analysis Philip Finnegan said, because those buyers are very similar to military purchasers. They’re more concerned about performance than they are about cost, and they have the budgets to invest in high-end, expensive systems. That’s not always the case in the commercial market, especially with smaller companies that are looking for ways to improve efficiencies and save money.

“We’ve seen some defense companies pull back from the commercial market because of this, but we’ve also seen some companies working early on to try to penetrate the market,” Finnegan said. “It’s generally not easy for military companies to get into the straight commercial market because first it’s a low-cost market. Defense companies are used to providing the highest level of performance without concerns about cost. The commercial market is different. It’s very heavily focused on cost.”

Photo courtesy Kongsberg Geospatial

THE CHALLENGES

Cost is one challenge, but there are others. One is that many commercial customers can get what they need with smaller UAS that weigh 55 pounds or less—and DJI continues to dominate there, Finnegan said. Most military systems are much larger and, of course, more expensive.

Also, defense clients and commercial UAS clients have very different business models, said Dave Duggan, precision engagement systems sector president for L3 Technologies, a New York-based defense company that is looking into the benefits of entering the commercial UAS space.

One of the biggest differences is the risk perspective, Duggan said. The government has a regulated contracting process where the balance of risk between government and contractor is very well known. Both sides understand how to negotiate and everything follows well-understood government acquisition regulations. Not so in the commercial world.

“A commercial customer might be willing to initiate a contract by sending an email or telling the company to start work,” Duggan said. “How they manage liability and risk and financing, all those things, is just a different model and way of thinking. It’s not bad, it’s a great model, but for companies that measure their risk profiles based on the government contracting process it can make your head hurt because you’re approaching things in such a different way.”

There’s also the fact the commercial space is so new, said Dave Kroetsch, vice president of UAS technology for FLIR Systems and founder of Aeryon Labs, of Waterloo, Ontario, which FLIR recently acquired. There aren’t really any established rules or requirements just yet and many business leaders interested in UAS are just starting to learn about the benefits the technology can bring. The military has a more tightly integrated group of customers than the enterprise space, which is made up of many smaller organizations that buy differently, need different things and have different expectations.

In the military, the main objectives are saving lives and ensuring mission success, and the risk and cost associated with those priorities are much higher than in the commercial space, said Daniel Fuller, senior solutions architect for Insitu Commercial, of Bingen, Washington. Commercial companies want to add efficiencies to their operations and collect data that enable them to make better decisions. These different needs require different payloads, and also post-processing ability, which wasn’t part of their business in the defense space.

The commercial market is much more fragmented, said Paige Cutland, vice president of sales and marketing for Kongsberg Geospatial, of Kanata, Ontario. He described the military space as a small pond with a lot of big fish, with projects that companies see coming for years. With the commercial market, they have to think about who they’re selling to, whether it’s first responders, service companies or any number of other industries turning to UAS. Hundreds of drone operators might benefit from using the technology, but they might only need one drone or a small fleet, whereas government clients buy hundreds of systems at a time.

“It’s a fire hose of potential customers, so it certainly takes a different mindset,” he said. “The commercial UAS industry is so new it has a start-up feel. There are so many new companies operating out of their basement, where the defense business is very well established and rigid in its process to buy things.”

Photo courtesy Bell Helicopters

COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGES

Yes, there are challenges defense companies must overcome to find success in the commercial world, but their backgrounds also give them many advantages that newer commercial-only companies just don’t have.

One is the analytical capabilities that enable them to understand aeronautical safety and reliability, Finnegan said. Many of these companies have a long-term background in UAS technology, and a financial well to pull from when designing new solutions or updating legacy products for use in commercial markets. They also have experience in aviation and know how to operate these systems.

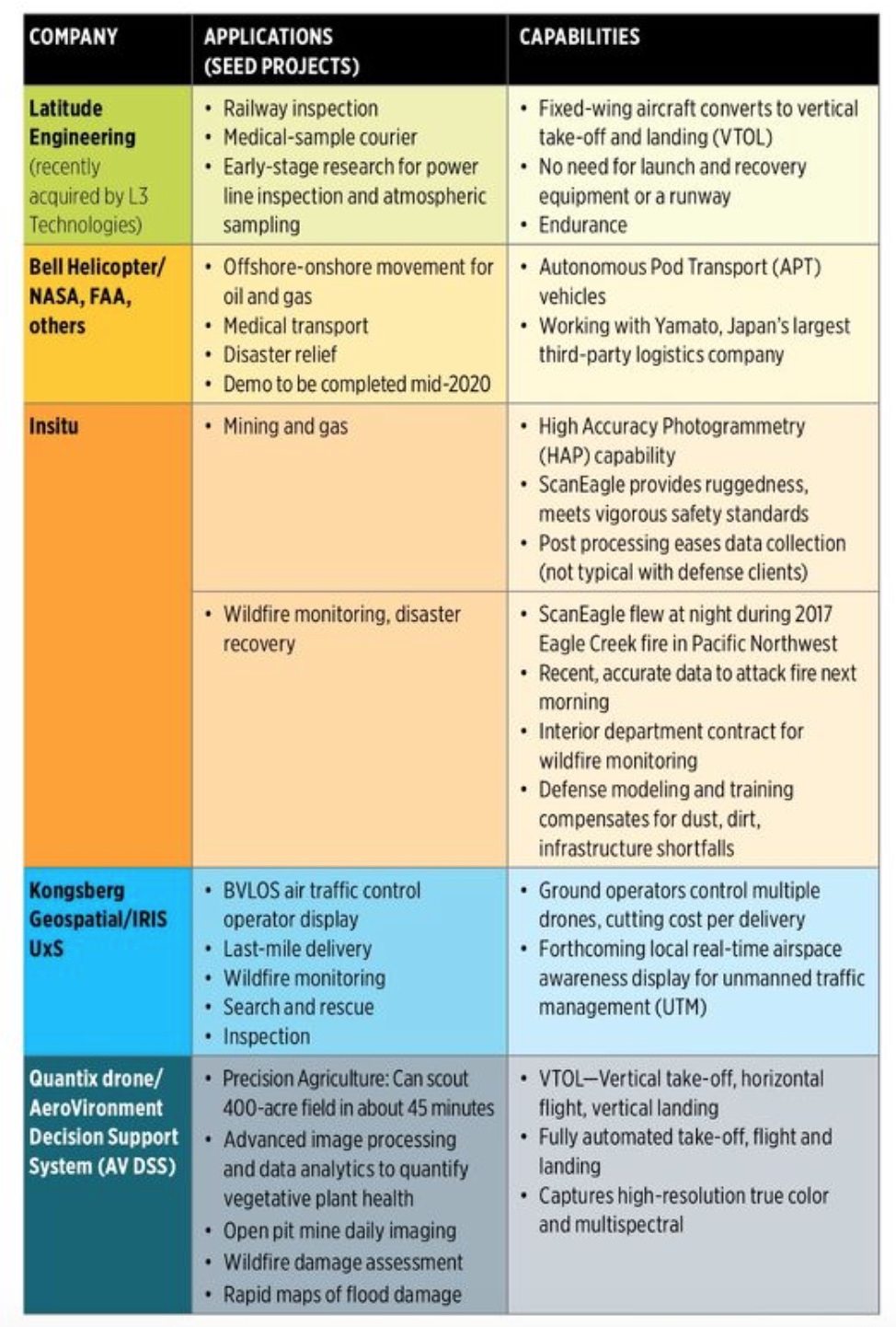

John Perry, founder and CEO of Altavian, in Gainesville, Florida, looks at the modular products his company develops as having dual use, making it seamless to take them from military applications to civil or commercial ones. For example, a solution developed for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was almost immediately used for civil applications such as levee inspection and wetland monitoring. So, in some cases, it’s easy to see the crossover between the military, commercial and civil worlds early on, and that’s exactly what Altavian looks for.

“The military’s approach to the technology is requirements-driven. What we typically see is the military has such a broad mission scope, there tends to be an overlap with commercial applications,” Perry said. “It’s more about finding that product’s market fit and transitioning the technology from defense to commercial or vice versa. I really believe it goes in both directions.”

FLIR thermal imaging cameras are used for a variety of applications in both military and commercial markets, said Dave Kroetsch, vice president of UAS technology for FLIR. In some cases, the same technology that’s used in military applications might also find its way into the commercial space. A sensor that’s used for search and rescue (SAR) missions in the military might also be used on a police SAR helicopter, for example. But others are too large and expensive for the commercial world, and require a lower cost and smaller footprint to work on commercial systems.

“We’re seeing a miniaturization of those technologies and a cost reduction to get into the commercial space,” Kroetsch added. “We’ve seen that with radar and LiDAR companies. The good news is this is beneficial for many markets because there’s overlap. The same LiDAR someone is building for the self-driving car market might be applicable for mapping missions on UAS. So there are economies of scale there.”

Companies like Fort Worth-headquartered Bell Helicopter, which is part of Textron, are commercializing military lessons, said Brian Duncan, Bell’s director of business development. Systems battle-proven in difficult environments with harsh climates have yielded knowledge for creating commercial solutions.

“We’re leveraging not only lessons learned but also the technology we’ve developed over Textron’s 30 years of experience in UAS and are reusing what we can in the commercial space,” Duncan said. “Everything comes with challenges, but we’ve been able to work with our sister companies so we don’t replicate the errors the rest of the industry went through. We talk to each other about how to improve the customer experience or product development. We have an open forum to do so. Other companies may not have that luxury.”

Being frequent lead adopters for new technology gives companies such as AeroVironment the opportunity to improve their capabilities, supply chain and intellectual properties for commercial customers, said Steve Gitlin, the Simi Valley, California company’s vice president and chief marketing officer. If a drone can successfully complete its mission during a military application, it likely will hold up just fine while flying commercial missions, even under extreme weather conditions.

“We understand the capabilities, we understand the logistics required to operate the systems effectively and we understand the risk involved,” Duggan said. “We understand what the technology’s limitations are and the integration aspect of how you pull all the pieces together to make a system work and operate effectively, meeting customer needs with a very high probability of success.”

THE FUTURE

As BVLOS flights become more routine and the need for larger UAS with more capabilities grows, Teal’s Finnegan sees potential for more defense companies to participate in the commercial market. But the jury is still out on how economical their products will be compared to non-defense companies.

“Prices are continuing to come down and are under pressure,” he said. “It’s a very dynamic market, but at the same time these companies are coming out with new products as well.”

Companies that view themselves as technology providers with solutions for civil, defense and commercial customers will continue to innovate. “We are strongly invested in the defense market and that is driving capability development that will translate directly to the commercial market,” Altavian’s Perry said, “whether a farmer is making better decisions because he has better data or infrastructure is better managed with timely geospatial data.”

One indicator of future commercial use is Bell Helicopter’s Nexus, an electric hybrid air taxi concept. Bell has partnered with Uber, and customers may be able to book a ride via an app on their smart phone by 2025, Bell’s Duncan said.

The opportunities are “astronomical”, L3’s Duggan said. It just comes down to overcoming the challenges and finding a way to translate defense experience over to the commercial world.

“I would anticipate we’ll see defense contractors moving in that direction as the market continues to open up,” he said. “It’s a matter of the companies wrapping their heads around the commercial business model and finding a way to provide a commercial service, a commercial model, that’s competitive. That will continue to take time. But the size of the market is undeniable.”