Colorado Contractor uses Drones, Software, Sensors to Track Work Progress

Drones and data processing software are becoming indispensable tools for the construction industry, saving time and giving company officials unprecedented insight into progress on work sites.

In the world of using drones for construction, Justin Russell, senior surveyor for Fiore & Sons Inc., a Colorado civil contractor, is a frequent flier.

“It really depends on the project,” he said of his flight schedule for the Denver-based company, which specializes in earthwork, sitework and finish grading, overlot grading, demolition, structural excavation and other construction-related work. “A minimum of once a week, sometimes two or three times a week, depending on how fast we’re moving on the project.”

Russell flies a DJI Phantom 4 RTK drone, which stores satellite observation data for use in his drone survey software, Trimble Stratus powered by Propeller, which uses a post-processed kinematic, or PPK, workflow. The company also recently added a DJI Mavic 3 Enterprise series drone, a new model that carries a 4/3 CMOS wide-angle camera, a 1/2 inch CMOS telephoto camera and a thermal camera.

Trimble Stratus is a turnkey 3D drone mapping and data analytics solution for civil construction and earthworks operations developed by the drone survey software company Propeller Aero. Russell also uses the company’s smart ground control points, AeroPoints, ground control points to aid in surveying. The end result: a 3D surface point cloud he can use to make adjustments to any earth-moving or foundation work his team has done for its commercial customers.

Russell said an interesting fact is that having the data often means they don’t have to make any adjustments now because they can catch and correct for mistakes even before they happen.

“We track the project to see what we have moved, making sure we’re on budget and schedule, what’s still left to move. We can also identify mistakes that we’re making and try to resolve those, if we’re undercut [on foundation creation] and things. Actually, since we’ve gotten the drones, we’ve pretty much stopped all of that because now we’re able to see it and correct it from past data, correct it before it happens in the future, if that makes sense,” he told Inside Unmanned Systems.

It’s not just a matter of being precise. He said if there’s a foundation to be built, his company will dig below it, moisture treat the material under it and then build it back up. If that buildup is too low, “well, then we don’t get paid for that dirt that’s below design. So, if we can keep that as minimal as possible, that’s just money that we’re saving instead of just going out the door.”

All of Russell’s work with drones is done flying line of sight, generating point clouds of eight million to 20 million points. That is then processed using the Trimble Stratus powered by Propeller software platform, with PPK corrections, and outfitted within 24 hours.

“We’ll run around two, three flights a day and then upload them all to them [Propeller] and have them back the next day and all our data computed,” Russell said.

It’s all photogrammetry at this point, as LiDAR would only be needed if there was significant vegetation. For a stripped, construction-ready site, “photogrammetry is twice as accurate,” Russell said. “I’ve seen it clear down to a quarter-inch.”

THE DIFFERENCE

Russell began working with drones a little over four years ago, he said.

“Oh, it’s an amazing difference. You know, we used to either walk the site or do it on an ATV [all-terrain vehicle]. We were trying to get monthly topos [topographical maps] back then for billing. Since the drones came along and they’ve proven their accuracy, we’re really starting to track everything, like I said, on a weekly basis with the drones.”

Russell had been investigating drones for work, and Fiore & Sons hired a few companies to come fly and demonstrate their skills, everything from photogrammetry to LiDAR, but weren’t impressed.

“Then Propeller Aero came along and I kind of got hooked up with them through Trimble and I made them do probably a half a dozen flights for me, proving their data, before I really bought into it,” Russell said. “And then I had to go to my bosses and prove the data to them and they eventually ended up purchasing a drone and the processing and the rest is history. It really worked out well.”

He was the lone company flyer at the beginning, but now the Fiore & Sons has three operators, all of whom passed the FAA’s Part 107 certification.

The company’s work has won it fans with numerous repeat clients. “They keep coming back to us,” Russell said. “I don’t know if it’s 100 percent because of the data or the quality of work that we do, but I think it puts them at ease.”

Customers can get weekly or even daily updates, and “they’re loving the data. We’ve actually got a couple of clients that after we left a project, have called us back and hired me to continue flying it on a weekly basis so they can continue tracking everybody else’s work through the job.”

GROWING INTEREST

Russell’s experience with drones isn’t unusual, said Jim Greenberg, the product manager for Trimble Stratus, Trimble’s drone platform.

“They’ve jumped in whole heartedly,” he said of Fiore & Sons. “Justin flies a lot, and it’s very common when someone takes the leap into drones and Trimble Stratus, they get great value from it and it kind of permeates through the organization.”

Companies might initially be interested in just getting good aerial photographs, but learn they can do various comparisons using drone data, comparing changes from flight to flight or using the data to make sure construction is going according to the design.

“That’s really valuable for the surveyor, or the manager, for the earthworks, things like that,” he said. “And that’s what really drives it into the organization.”

Once people start seeing the data, it becomes “a really good collaboration point,” he said. “It’s a good way to know really basic stuff. How do you get onto the site? Where should I park my car? What’s the state of the silt fence? Just endless questions…so, the surveyors kind of use it because it has great value for them, and then everyone else benefits from it. We hear that a lot when we have sites where hundreds of people from the company log in, just to see what’s going on.”

That also means the people want updated flights, which means the surveyors have to provide them, “but it does help them to not be a bottleneck of information,” Greenberg said. “If they’re confident in the flight, they can share that with other people who can then answer questions from it. And we’ve seen that a lot.”

Trimble has a variety of software products useful for the construction industry, from Stratus to the Trimble Business Center (TBC) to Works Manager to Earthworks to Siteworks, each with a different role (Siteworks, for instance, would be located on a surveyor’s rover measuring device).

“The real strength of the system, whether it’s Stratus or TBC or whatever, is that they all are on a common coordinate system” and can work toward a common design, Greenberg said. “And it lives in the Trimble cloud, and data can be moved around through this program called Works Manager. Justin will use some subset of those on a regular basis. Like, he’s got a rover in his truck, he’s got a drone in his truck. Many of the machines on the site are running Trimble Earthworks, so they all have this common design that they’re all working toward, and that design can change and they put in a new design and they all work toward a new design.”

WISH LIST

Russell said he is happy with the capabilities of his current drones. The Mavic 3E has an active terrain awareness, which detects where the ground is and maintains the same height above the ground at all times, where older systems like the Phantom 4 just maintain a certain altitude regardless of the ground level.

“That’s helpful. It’s not super accurate at the moment, hopefully they’ll get the bugs worked out of it, but that’s really nice to have.” Without it, he said, “if you have a big, deep valley, you’ll lose some accuracy at the bottom of the valley because you’re not getting the same ground sampling distance.”

DJI’s Matrice 300 has a feature Russell would also like to see on smaller drones, that being a laser rangefinder, where you can put your crosshairs or your camera on something and highlight it and it will give you the coordinates of it.

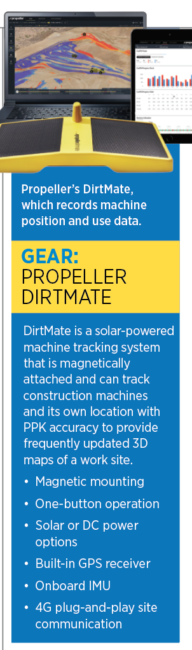

He’s a big fan of a new system—Propeller’s DirtMate, a magnetic, GPS-equipped sensor system with an onboard IMU for which he is an early tester. It tracks both what a given machine is doing and where that machine is.

“Mounted on the cab of machines on site and equipped with GPS, DirtMate continuously provides machine location and elevation. DirtMate surveys and captures the ground beneath tires or tracks to automatically generate key production data every day, on demand,” Propeller says in describing the system.

“They’re little magnetic rectangles,” Russell said. “They’re solar powered. You can put them on any machine and you just do a quick measure up from the center of the DirtMate down to the edges of the tires.”

That goes into the DirtMate app, which is connected to a datalink. “Anywhere that machine drives, he’s getting a new topo, it’s building onto that original drone topo. So, as they’re cutting a hole every day, as each machine goes by, it’s re-measuring that hole. So, we are literally getting, it’s probably three to five minutes old, the information we’re getting off of it.”

Greenberg said DirtMate is a complement to a drone; a drone might fly once a day or once a week, but the DirtMate can be collecting data all the time, “so in between flights, you get your production data.”

PPK

The DJI drones have built-in RTK modules, but Russell flies them in PPK mode, which Greenberg said is more robust.

“In a traditional kind of photogrammetry, you just have points on the ground and those points are referenced in photometric process, and so those are what kind of define your end product,” he said.

With PPK, users are logging data on the ground and in the drone, and there are “triggers” in the file as to when the drone’s camera took an image. Those positions are known relative to the base station on the ground. If a drone took 1,000 images there are essentially 1,000 control points, plus the ones on the ground.

“If you don’t have PPK capability, you’re just relying on the ground and the geometry of your points on the ground to give you a quality deliverable,” Greenberg said. “The PPK just makes everything very consistent and really gives you a consistent end product to this high level of accuracy.”

PUBLIC ACCLAIM

Greenberg couldn’t say what the market penetration rate is for construction companies using drones and the related software tools, but “it’s growing faster than any other technology.” The industry is very mature in rovers and machine control, “but drones are just taking off,” he said.

Site surveyors have rovers in their trucks and now they’re going to have drones in their trucks, he predicted. “It’s just the right tool for the job in many situations. It’s just another tool, but it’s a phenomenal tool that everyone can identify with. When you see a site in 3D with a really clear image, it just tells you so much.”