Until unmanned aircraft can routinely fly beyond visual line of sight of operators, the full value of the technology won’t be unlocked. Many efforts are under way to make BVLOS a reality, but safety must be assured.

For many industries, deploying drones has become routine, and the impact they’ve had is undeniable. They’re making inspections safer, repeatable and easier across various industries from utilities to oil and gas. They’re capturing imagery in places once unreachable, allowing scientists to expand their research and surveyors to capture difficult terrain from a distance. They’re monitoring and spraying crops, delivering medicine, food and other goods, detecting costly pipeline emissions and providing valuable insights to first responders before they arrive on scene, to name a few use cases.

This emerging technology brings with it many possibilities, but it also has its limitations. As of today, operators can’t fly BVLOS without a waiver from the FAA, a process that, while improving, is time-consuming. But until we reach a point where drones are routinely flying BVLOS, it will be difficult to scale and for the technology to reach its full potential.

BVLOS is an industry priority, with UAS test sites, manufacturers, the FAA and other stakeholders all working toward that same goal. It’s a difficult problem to solve, and while we’ve come a long way since the early days through programs like the FAA’s BEYOND, there’s still a long way to go.

Regulations are a hurdle, and while some say the technology is basically there, others argue it’s not. Advancements have been made, but the technologies required are complex and must ensure safety.

Regardless of the challenges, the industry is eager for the freedom to fly BVLOS. Operating UAS remotely, or allowing them to fly autonomously, will eliminate the need to have people on site, significantly cutting costs, improving efficiencies and enhancing safety.

“The whole industry wants to see the FAA get to a rule for BVLOS, something that’s codified and printed in a book and that’s clear about what we need to comply with. That’s how it is in general aviation,” Iris Automation CEO Jon Damush said. “That will open the market up, but it’s not a fast process.”

THE REGULATION SIDE

When Part 107 was released in 2016, it was a huge breakthrough, finally giving commercial drone operators a way forward for UAS less than 55 pounds and the opportunity to request waivers for various missions, including BVLOS. But there hasn’t been much change since, said Neta Gliksman, Percepto vice president for policy and government affairs, at least in terms of BVLOS guidance.

There has been progress, though. At first, waivers were hard to come by, but that’s shifting, with review time shortening and the number of approvals increasing.

“At the waiver level, broadening approvals beyond site-specific authorization is growing in popularity,” said Reese Mozer, president of Ondas Holdings and co-founder and CEO of American Robotics. “This is often referred to as ‘nationwide approval,’ but what it really means is approving BVLOS operations for environments with particular characteristics, such as a certain population density, over private property, within a certain distance to structures. This is an important step forward to making the approval process more scalable for commercial drone companies, and is a precursor to an eventual national rulemaking process.”

And we’re getting closer to such rules. Last March, the Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC) came out with recommendations for BVLOS regulations that would allow for operations the technology makes possible today, Gliksman said.

The FAA has used the report to develop different types of BVLOS approvals, Damush said. Shielding is an example, recognizing that if a drone is flying close to infrastructure for an inspection, the chances of another aircraft in that airspace is pretty low, making it safe to fly BVLOS.

Operators are also starting to receive waivers for real commercial work, not just for testing, Damush said. In many cases, they’re flying under shielding or using a visual observer, but they’re still expanding what they’re able to do.

“This allows operators to spool up business and get off the testing treadmill,” he said. “Let’s deploy, watch it and if it’s safe we’ll start to scale slowly while we wait for a new rule to come out.”

And when might that be? Probably a few more years. The next step is a notice of public rulemaking (NPRM), with the draft expected to come out later this year or early next, Damush said. The public comment period will last 18 months to two years before any rules can be put on the books.

One of the issues that needs to be addressed in the final rules is right-of-way, Gliksman said. Safety is paramount to the commercial drone industry and Gliksman believes we can continue to make it even safer. The ARC’s proposed rules recognize the evolving shared and collaborative nature of the airspace.

“Times have changed, and commercial drones are now part of the National Airspace System,” she said. “With the societal benefits that come with drone technology, they are not a ‘nice to have;’ they are very much a ‘must have.’ The ARC therefore recommends that pilots who operate at low altitudes (under 500 feet) should adopt existing, effective and affordable technologies such as ADS-B that have been proven to substantially reduce the likelihood of mid-air collisions and improve overall safety.”

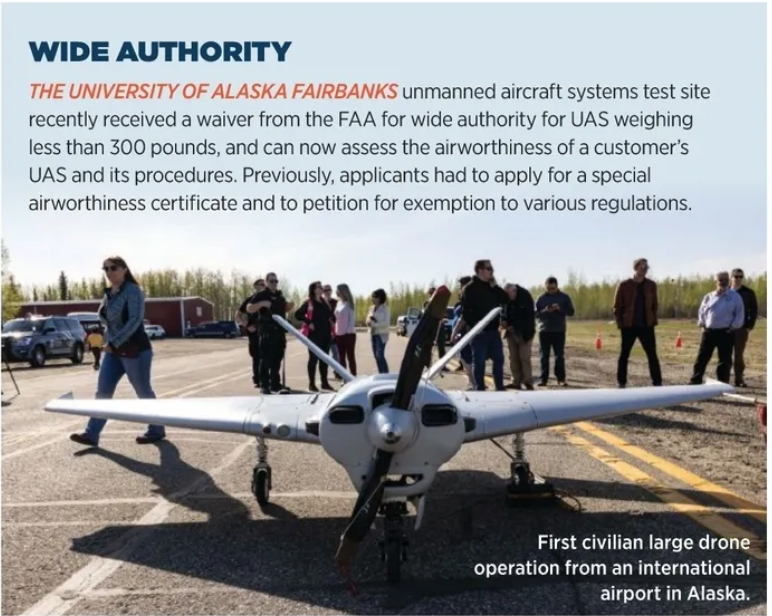

Type certification is another key area, said Catherine Cahill, director of the Alaska Center for Unmanned Aircraft Systems Integration at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. With the durability and reliability rules the FAA has put out, there’s a path forward, but that path isn’t exactly clear.

Operators who want to perform BVLOS cargo delivery missions for payment also need a Part 135, which carries a much heavier regulatory framework that’s similar to commercial airlines.

“This is going to be a major stop gap because you can’t do a true Part 135 for cargo delivery until you have a type-certified aircraft,” Cahill said. “That’s a major limitation. And you also need appropriate training and maintenance. With a Cessna that’s been used for decades you know what the maintenance schedule is. With drones, we don’t know yet how long it takes something to fail.”

There have been advances in type certification for UAS, with Matternet among the companies receiving one. Airobotics is in the final stages.

Spright is working toward type certification, what Bill Wimberley, the company’s vice president for Strategic Programs, describes as a vigorous and expensive process. But he’s pursuing it because he believes one day commercial drones will be required to have it.

Flytrex partner Causey Aviation Unmanned recently received a Part 135, allowing Flytrex, a drone delivery service, to expand stations, although going national is likely still a year out, CEO and cofounder Yariv Bash said. The company currently delivers to homes in North Carolina and Texas.

Operators are learning more about the regulatory process, with many gradually asking for approvals for more complex, longer flights as they’re able to illustrate they can perform missions safely.

“BVLOS is that elusive gold standard everyone is trying to get to,” said Trevor Woods, Northern Plains UAS Test Site executive director. “Everyone is still trying to find a pathway to get there in a repeatable, scalable way. And there’s no one solution that’s going to solve the problem right away. It’s going to take a lot of time to get there. It’s been a very slow progression with little wins here and there, but there’s still a lot of work to do.”

THE TECHNOLOGY

From a technology standpoint, all the pieces of the puzzle exist, Damush said, and we’re starting to see more integration of those pieces.

Safe BVLOS requires reliable aircraft that has the necessary endurance and doesn’t require much pre-flight, he said. They must be operated remotely, which means they need a secure, clear communication mechanism that connects the pilot with the UAS no matter how far away it is.

Then there’s collision avoidance. The problem can be split into two, Bash said: cooperative and non-cooperative aircraft. Drones are equipped with the technology to identify cooperative aircraft with the appropriate transponders, but non-cooperative aircraft are another issue. It falls on the drone to avoid a collision, going back to the right-of-way issue and making detect and avoid a necessity.

These systems can be ground based or on the aircraft, Bash said. While nothing eliminates the risk of collision 100%, the onus is still on manufacturers to keep the skies at least as safe as they are today, meaning such technology has to demonstrate it can handle all situations.

Northern Plains UAS Test Site, in partnership with Thales, is focusing on the ground-based option with its statewide Vantis. Vantis essentially creates a road system for drones by deploying radars and sensors across the state, attaching them to existing infrastructure, Woods said. Vantis also monitors how everything is working together in real time, letting operators know if something isn’t running as it should.

The challenge? Deploying such systems across the country will be expensive, and may not work everywhere.

That’s the case in Alaska. An onboard system is required for UAS to safely fly through the mountains and in GPS-denied environments, where many aircraft are non-cooperative and establishing a command and control link is problematic, Cahill said. Use cases they’ve tested range from cargo and medical supply delivery to remote villages, wildlife surveys, mapping glaciers and highways, and monitoring the Trans Alaska pipeline. They’ve also flown from the Fairbanks International Airport, a first step toward integrating drones into the airport environment. This spring, they’ll fly from Fairbanks to a town 40 miles away.

Onboard detect and avoid adds weight, though, reducing precious payload capability. Companies are working to address this, miniaturizing the systems, one of the advancements Wimberly notes along with camera optimization.

“Aircraft must have proven reliability, the right kind of communication technology that can run longer ranges and see and avoid all other aircraft in the airspace system,” Woods said. “This technology all exists, but it’s not been robustly tested or integrated in such a way where we flip a switch and the problem is solved.”

WHO’S FLYING NOW

There are various applications where BVLOS significantly changes the game, including infrastructure inspection, emergency response and parcel delivery.

Infrastructure and Medical

For infrastructure inspections, drone-in-a-box solutions could fly an asset, record the necessary data and then head back to home base—all without human involvement, Damush said. That allows for remote operation, making the application safer, more affordable and scalable.

Percepto has received several BVLOS waivers, including permission to fly its drone-in-a-box solution for highly automated BVLOS missions at a Texas solar plant. Remote operations are approved for 200 feet, with just the system, its base and the radar to deconflict the airspace on site. Cameras around the base allow pre-flight checks to be handled remotely. Percepto had requested an exemption for this but the FAA said it wasn’t necessary, thus allowing the practice for the entire industry.

Soaring Eagle Technologies recently received a non-geographical restrained waiver to fly anywhere in the U.S. for infrastructure inspections under certain operating parameters, President Will Paden said.

“It’s no longer, I can only fly this corridor or this pipeline or utility line. It’s based on our ability to properly analyze the mission and the FAA trusts that our processes mitigate to a safe level,” he said. “It’s a complete shift in mentality; it’s no longer an approval to do a mission, it’s an approval to go operate.”

Paden expects more companies will present enough data to receive these types of blanket approvals.

Spright recently received a nationwide unrestricted BVLOS waiver for utility inspection, but it has limitations, such as requiring visual observers. While Wimberley said it’s still difficult to get a waiver, the company’s focus on utilities and medical delivery makes the process easier than if they were in parcel delivery.

“In the medical industry, we fly from point A to point B; we know exactly where we’re going to fly and we fly back and forth to the same place over and over,” he said. This is called Business to Business (B2B) as opposed to Business to Consumer (B2C) delivery. With utility inspection, we are flying the electric grid along known routes and usually above, or within the utility’s right-of-way. So, you can discuss with the FAA how you mitigate risk. They’re much more likely to open the skies in those scenarios.”

FlightOps, which offers a cloud-based flight automation software infrastructure, also works on the medical side, with partners flying on hospital campuses between labs to emergency rooms, carrying tests and light medical equipment, CEO and co-founder Shay Levy said. Recently, an autonomous drone controlled by the FlightOps multi-drone operating system completed Israel’s longest autonomous medical equipment delivery via air, carrying blood units 15.5 miles without compromising sample quality.

Emergency Response

Drones serve as force multipliers for first responders, giving them eyes on a scene so they can prepare and better allocate resources. Ideally, systems, located at various spots throughout a city can be deployed when a call comes in, with data automatically streamed to a central command center.

BVLOS is particularly useful for coordination among agencies during disaster response and in search and rescue operations (SAR). Iris has worked with the City of Reno for years, developing use cases to support first responders during river rescues, Damush said. They recently received their third waiver on behalf of the city of Reno’s fire department for SAR in a test environment near the Carson River. The waiver allows operations without visual observers over a limited operational area based on a network of two Casia G nodes, the company’s ground-based system. This could enable a grid of Casia G systems to provide airspace awareness of non-cooperative aircraft.

Airobotics, a subsidiary of Ondas Holdings, became the first to deploy autonomous drone fleets in a city, with drone-in-a-box systems operating daily to support the Dubai Police, Mozer said.

The company also is deploying a network of Airobotics’ Optimus Systems in Abu Dhabi at industrial and municipal sites. Eventually, the area will be covered with Airobotics’ autonomous drones, resulting in 20 to 25 Optimus Systems being installed in each city over the next two to three years.

Delivery

Even though many agree BVLOS parcel delivery will be much more difficult to achieve, it still has huge potential.

“In a delivery scenario, covering 1,000 meters radius would only cater to around 100 households, whereas covering 10 miles radius would expand the coverage to about 50,000 households,” Levy said. “This highlights the significant impact of BVLOS on service providers, as it allows for larger business volumes and more extensive customer reach.”

Flytrex was the first to receive approval to cross a highway for delivery, Bash said, paving the way for other companies. Now, they can fly up to two nautical miles and deliver 6.5 pounds of goods to people’s backyards, traveling over highways hundreds of times a day and operating as many as four drones at once.

Drone deliveries will start to become more common in suburban areas first, Bash said, and are more economical for restaurants, eliminating fees and allowing quicker deliveries. If one operator manages four drones, each can make four to five deliveries in an hour. A delivery person in a car can maybe make two.

Opening up the Market

BVLOS will open up a new world of opportunities for drones in these and other industries, allowing operators to perform long-range missions more efficiently.

“With BVLOS, we truly have the capability to remotely operate, which means mitigation of labor and mobilization costs,” AviSight CEO Suzanne Herring said. “BVLOS assists in providing the customer actionable data more efficiently and service provider costs related to labor and mobilization decrease approximately 60%.”

WHERE WE’RE GOING

Gliksman sees a future with updated regulations, a sort of Part 108, that enables commercial drone operations to scale across various use cases.

The technology will continue to advance, with BVLOS operations with multi-drone approvals, such as one remote operator overseeing multiple autonomous drones and autonomous flights over populated areas, on the horizon, Mozer said.

Wimberley expects many to gain experience flying BVLOS outside the United States, in countries with more open skies.Industry and the FAA can learn from these flights and those performed domestically, further informing rulemaking.

But getting to routine BVLOS will take companies continuing to work closely with the FAA, Herring said. While staying in touch with her liaison provides tremendous benefit, she’d like to see improved continuity and communication with flight standards. For example, obtaining a better understanding and clarity with respect to the FAA’s uniform expectations on the composition of a waiver application to ensure a successful outcome.

Safety will remain top of mind, with properly training pilots critical, Paden said. He would like to see standard safety aviation training become a requirement. As it stands, there isn’t enough focus on training. Safety and maintenance programs as well as general operations manuals also should be developed.

When all the pieces come together, opportunities will abound. Until then, the industry waits and continues to innovate.

“Right now, not much is commercially viable from an ROI perspective because we can’t fly BVLOS and we can’t increase the activity level,” Wimberley said. “For a project to turn economically viable, you must have more freedom to fly BVLOS. The industry will not be broadly economically viable until we get closer to that level.”