The ability of unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) in the energy sector to gain efficiency, decrease costs and increase safety continues to grow. Now, autonomous BVLOS ops are key to unlocking scalability, the greatest value for business operations and strategies. In fact, some refer to BVLOS as the “Holy Grail.” Like the fabled chalice, it remains highly desired and yet equally elusive. As with the classic movie “Monty Python and the Holy Grail,” will the quest become a comedy of errors? Or can it be successful and rewarding?

The Knights Who Say “Ni!”

The reticence of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to permit extended BVLOS operations is deeply rooted in history and tradition, codified in regulation. Even before the relevant Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) provisions were written, Civil Air Regulations (CAR) Sections 60.13(c) and 60.30 required pilots to focus their attention outside the aircraft to prevent mid-air collisions.

In the FAA’s 1968 rulemaking, the assumption that there would be a pilot onboard who could “see and avoid” other aircraft persisted. Regulation 14 CFR § 91.113, Right-of-way rules: Except water operations, states in subsection (b) General:

“When weather conditions permit, regardless of whether an operation is conducted under instrument flight rules or visual flight rules, vigilance shall be maintained by each person operating an aircraft so as to see and avoid other aircraft. When a rule of this section gives another aircraft the right of way, the pilot shall give way to that aircraft and may not pass over, under, or ahead of it unless well clear.”

Those drafters could not imagine the day that detect and avoid (DAA) tech could replace human vision. That day has dawned. Iris Automation currently offers Casia 360, the first commercially available 360-degree radial computer vision DAA system for UAS, an integrated onboard hardware and software solution.

Despite tech advancements, Part 107 (Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems) still requires visual line of sight (VLOS) for small UAS operations in Part 107.31. Specifically, it requires a remote pilot in charge (RPIC) to: (1) know the UAS’ location; (2) determine the UAS’ attitude, altitude and direction of flight; (3) observe the airspace for other air traffic and hazards; and (4) determine that the UAS does not endanger the life or property of another, throughout the duration of the entire flight. 14 CFR § 107.33(b) and (c)(2) further requires each VO (visual observer) who is participating in the operation to see the unmanned aircraft in the manner specified in §107.31.

Part 107.37(a) is also important. It states, “Aircraft must yield the right of way to all aircraft, airborne vehicles, and launch and reentry vehicles.” Again, no going over, under or ahead of the other vehicle. Part 107.37(b) reinforces the point: “No person may operate a small unmanned aircraft so close to another aircraft as to create a collision hazard.”

Thus, collectively these VLOS requirements essentially apply to all UAS, regardless of type or purpose. Non-public use UAS (private or commercial operations) restrictions are contained within 14 CFR Part 107. 14 CFR § 91.113 applies to public use UAS (governmental or military), with possible additional restrictions in the FAA Certificate of Authorization or Waiver (COA) that authorizes flights.

Yet, as with most rules, waiver may be possible. Commercial sUAS users can request waivers from some Part 107 restrictions, including the fundamental Part 107.31. The requestor must provide a safety case to convince the FAA that operating outside normal parameters can be accomplished in the national airspace without compromising safety to citizens and property on the ground.

Consequently, the quest for BVLOS ops that began in 2016 with the passage of Part 107 continues today.

“What…is the air-speed velocity of an unladen swallow?”

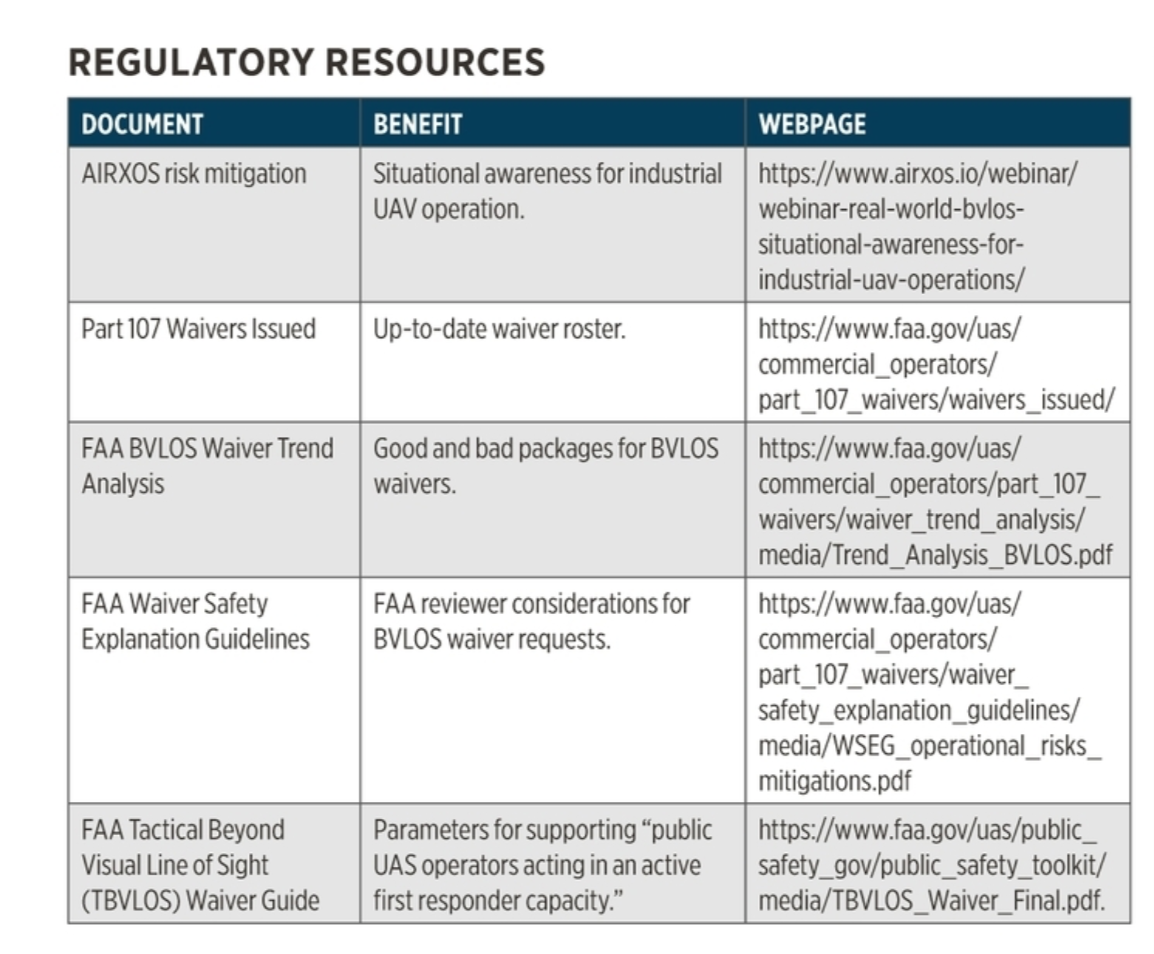

Obtaining a BVLOS waiver may not be quite as difficult as answering the questions posed to King Arthur and his Python knights as they attempted to cross the Bridge of Death. In a September 2020 Energy Drone & Robotics Coalition webinar, Jim Rector, AiRXOS senior director flight operations and technical business development, opined, “It comes down to the basic blocking and tackling. What’s the air risk? How are you mitigating it? What’s the ground risk? How are you mitigating it?” (See the “Regulatory Resources” table.)

Some energy companies have answered these questions successfully. Florida Power & Light Company, Dominion Energy and Xcel Energy all have received BVLOS waivers in the past two years; some more than once. Florida Power has been using Percepto, a leading provider of autonomous drone-in-a-box (DIB) solutions, for monitoring and securing critical infrastructure and industrial sites. Percepto is the most-deployed AI-driven DIB solution in the market, with Fortune 500 customers in more than 10 countries, including Israel, which just granted the company BVLOS approval. In the U.S., the FAA also recently authorized Florida Power to fly Percepto’s UAS BVLOS within a range of up to two miles.

In fact, BVLOS-waiver “how to” information abounds. Besides the actual waivers being posted online, the FAA also uploads a “Waiver Trend Analysis” that captures developments in areas such as “Links and Emitters Performance Capabilities,” “Detect and Avoid (DAA) Methods,” “Weather Tracking and Operational Limitations” and “Training Requirements.” It also provides “Waiver Safety Explanation Guidelines” detailing the issues that will be evaluated during waiver renewal (see “Regulatory Resources” for links). The FAA’s educational campaign further includes UAS Symposia. In 2019, FAA staffers discussed tech’s detection abilities, automated/human responses, and evaluation and validation.

Besides the handful of energy companies that have obtained BVLOS waivers, other industries have had success. After State Farm Insurance proved it could safely operate sUAS BVLOS and ops over people (OOP), the FAA granted BVLOS (and OOP) approval for the company to fly in sparsely populated areas. This is relevant because many energy sites are similarly remote.

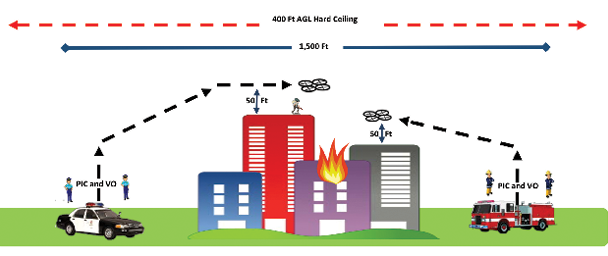

Perhaps even more relevant—if only because the use case is arguably more risky than anything the commercial energy market would require—is the FAA’s recent approval of a tactical BVLOS (TBVLOS) waiver for first responders. It provides the public safety community temporary authority in extremis (to safeguard human life) under Part 91.113(b). Examples of such emergencies include “a scene at a large structural fire, to conduct an aerial search on a large roof area for a burglary in progress, or to fly over a heavily forested area to look for a missing person.”

Applications can reach the FAA by sending a “Concept of Operations” (CONOPS) through a special email (9-UAS-91.113Waivers@faa.gov). Once approved, the next step is to forward that approval to the FAA’s COA Application Processing System (CAPS) for the TBVLOS 91.113(b) waiver. (See “Regulatory Resources” for a link to the FAA’s TBVLOS Waiver Guide).

This accessibility is good news for the emergency responder UAS community. But what about the rest of the UAS knights?

Image courtesy FAA

“It’s Just a Minor Flesh Wound”

Waiver approvals aren’t being hacked to pieces, as was the Black Knight in the Python film. But despite progress, they seem to be moving at the speed of government. According to Gabrielle Wain, VP policy and government affairs for Iris Automation, “Receiving approvals to fly beyond visual line of sight is a complicated and tedious process. Completing the applications from civil aviation authorities can feel like a bit of a black box for our customers. The level of risk assessment required makes it seem like achieving a waiver is nearly impossible.” The facts seem to support this: In the four years since Part 107 was issued, the FAA has only issued 59 BVLOS waivers.

Perhaps the good news is that a little more than one-sixth of those BVLOS waivers were issued in 2020 alone. R&D also continues. In September, the North Dakota’s Northern Plains UAS Test Site (NPUASTS) partnered with Collins Aerospace (Charlotte), L3Harris Technologies (Melbourne, Florida) and Thales USA (Arlington, Virginia) to build the required infrastructure and test it using the Voly C-10 drone. The end goal: a state-wide BVLOS network.

Meanwhile, compelling safety cases have resulted in BVLOS waivers. The FAA has even established a special email inbox and process to expedite TBVLOS waivers. Why not take that step for the Part 107 crowd—especially the energy sector? Unlike urban-based first responders, many energy asset sites are rural or remote. It’s certainly not as incendiary an option as deploying the Holy Hand Grenade of Antioch.

Perhaps the grail may be within reach.

Sunshine State Waivers

The Florida Power Part 107 waiver certificate includes operating provisions that seem to be standard across the board:

- RPIC/VO Knowledge: The remote pilot in command and other operations personnel need to know waiver rules and terms, and be trained in compliance with FAA regulations.

- VOs: A minimum number of visual observers (VOs) are required to identify any non-participating aircraft before entry into at least a 2 statute mile radius of airspace surrounding the sUAS in flight.

- Documentation: RPIC/VO knowledge has to be documented; the waiver must be with them; there must be a list of pilots and UAS operating under the waiver; ops manual and pilot training certs both need to be handy.

- Compliance: Ops must comply with one’s test plan and compliance manual.

- Safety Briefings: All direct participants must attend a safety briefing that addresses waiver-listed requirements.

- Communication: Comms must occur between the PIC (pilot in command) and VOs to facilitate sUAS maneuvers. Specific requirements exist for electronic devices: emitters must be FCC-compliant; redundant comms are required, ADS-B out (1090/978 MHz) is prohibited.

- Stop-OPs: The FAA can call a stop and ops must cease per non-compliance or safety issues.

- No Packages: No sUAS flights may carry another’s property for compensation or hire without a separate waiver.

- Ground Stations: In real time, ground control stations (GCS) must display altitude, position, direction of flight and flight mode.

- Warnings: The sUAS must audibly and visually alert the RPIC of degraded system performance, sUAS malfunction, or loss of Command and Control (C2) between the GCS and the sUAS.

- Lost Link: In cases of a lost link, the sUAS must follow a predetermined route to immediately reestablish a C2 link.

Disclaimer

*The views and opinions in this article are those of the author and do not reflect those the DOD, do not constitute endorsement of any organization mentioned herein and are not intended to influence the action of federal agencies or their employees.

Dawn M.K. Zoldi (Colonel, USAF, Retired) is a licensed attorney and a 25-year Air Force veteran. She is an internationally recognized expert on unmanned aircraft system law and policy, a recipient of the Woman to Watch in UAS (Leadership) Award 2019, and the CEO of P3 Tech Consulting LLC.