The Department of Defense is using industry consortia and a contracting mechanism called Other Transaction Authority to attract innovators who normally shun government contracting

Though much of the global economy remains immobilized by the pandemic, there are still pockets of activity and opportunity for unmanned technology firms if they know where to look. Some of those options rest within the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD), which has been reaching out to the private sector for solutions to a wide variety of problems.

Impressed by the rapid innovation of the commercial sector, defense officials are adapting to secure more participation from tech-focused firms. They’ve organized dozens of industry consortia to improve communications and reduce unintended barriers created by the Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR), which can include complicated accounting, deeply involved proposals and limits on communications, including no communication between bidders and the government once the solicitation is released.

To do this, they are using a special contracting capability called Other Transaction Authority (OTA) to streamline the partnering process and cut costs to a level where small entrepreneurial outfits can participate. The government also has used OTA to scale successful research and prototyping projects into larger production contracts. Most importantly, firms working under an OTA contract don’t have to give up their intellectual property (IP) rights to get government business—those rights are negotiated so future commercial applications are not precluded.

CONSORTIA ARE KEY

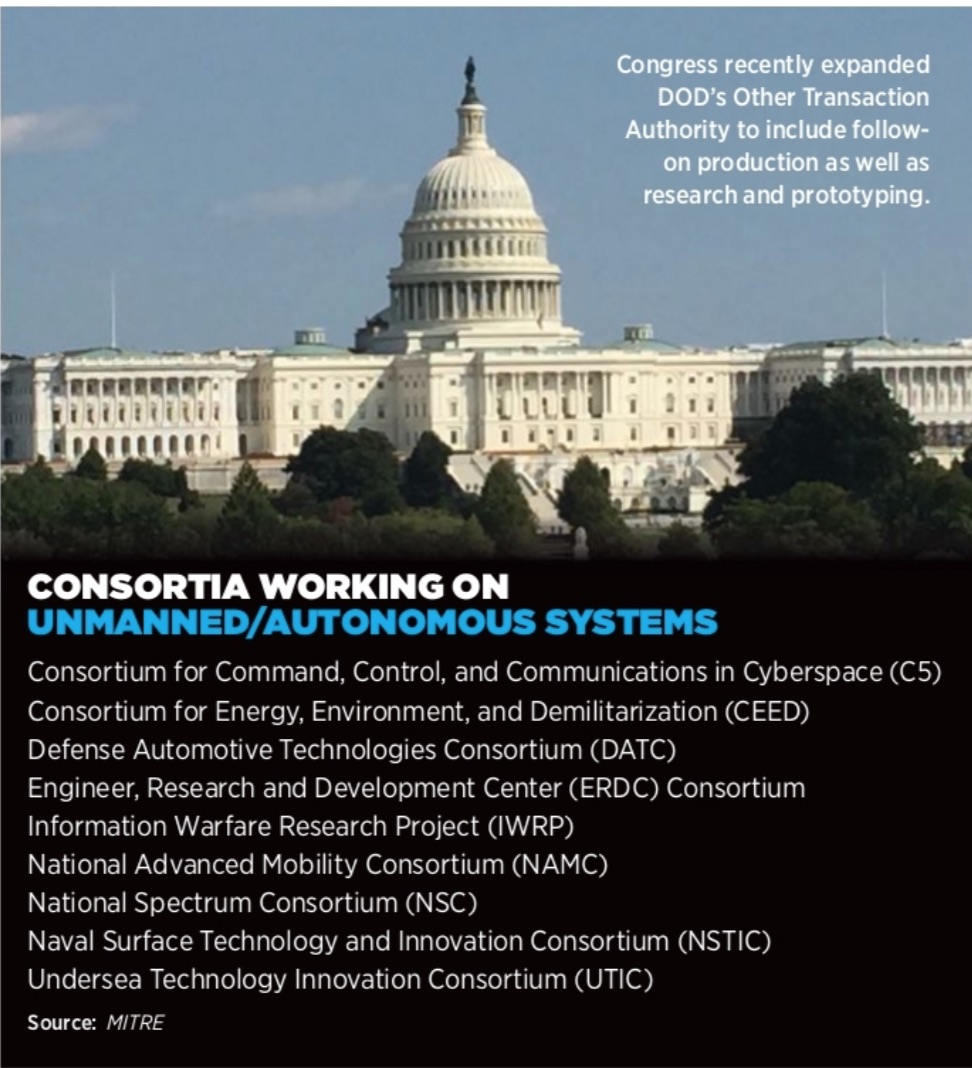

Enabling the use of OTA are dozens of industry consortia that provide the structure for contract administration and collaborative communication between firms and DOD program managers. According to a list maintained by MITRE, the non-profit organization that manages federally funded research and development centers (FFRDCs) supporting various federal agencies, the DOD had 30 consortia of varying sizes as of mid-February. The majority either have unmanned technology listed explicitly in their research portfolios, are working on problem sets that could use autonomous platforms or are developing technology that could support unmanned systems.

The National Advanced Mobility Consortium (NAMC), for example, was originally called the Robotics Technology Consortium and was launched to help develop unmanned ground vehicles. AUVSI (the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International) is a NAMC affiliate. The Consortium for Energy, Environment, and Demilitarization (CEED) has unmanned systems and robotics among its 19 technology focus areas. At least seven more have either unmanned systems or autonomous technology specifically listed as a technical focus.

A full list of the consortia can be found at https://aida.mitre.org/ota/existing-ota-consortia/

MAKING IT EASY

Most defense consortia are run by dedicated nonprofits, with Advanced Technology International (ATI) managing the greatest number, followed by the Consortium Management Group (CMG). A few groups using OTA are run directly by the government.

That said, structure within each consortium can vary. Some have boards of members who set their operating rules. Some only allow U.S. companies to join, while others welcome international members.

The communication of opportunities is where variations between different consortia become the most clear. Some consortia and their sponsors announce opportunities on Sam.gov while making clear that the work itself will be done via the group. Some publish very brief summaries about what is on the horizon with the details available only to members. Other consortia, sometimes for security reasons, only communicate in-house, so you have to be a member to find out what the government is looking for.

Fortunately becoming a member is not that difficult. An annual membership fee of $500 a year is typical, with perhaps a somewhat higher fee for larger companies. To join, companies generally must fill out a Military Critical Technical Data Agreement (DD form 2345), which is quickly vetted by the government. Once they are members, firms can tap fully into the flow of information about what the different defense programs say they are looking for.

This information can come via regularly scheduled briefings, notices or on an as-needed, quick-turnaround basis. Such informal, collaborative communication is one of the most valuable aspects of the OTA approach, said Bob Tuohy, the former chief operating officer of ATI.

“The government and industry can sit down and talk about problems, and we [ATI] facilitate those meetings,” Tuohy said. The government presents a problem to the membership and they come back and talk about what is possible. Those conversations inform the writing of the requirements, so when they come out “the members of the consortia really understand what the government’s asking for.”

Response to a solicitation generally sparks internal conversations too.

“Soon as a solicitation comes out,” Tuohy said, “we start doing things like having industry days—sometimes in person, sometimes virtual, sometimes both.” ATI helps with matchmaking between members to form teams using tools like speed networking, during which small companies get 10 minutes or so to brief their technology to the larger integrators. Those large member firms, such as Raytheon, are often essential to a project, Tuohy. said. “And so the Raytheons sit down and…they listen to these non-traditionals pitch why they think their technology will be a big enabler to help solve the problem that the government has asked for.”

The nontraditional companies that don’t normally work with the government are actually the focus of the OTA structure, and the consortia are designed to help them adapt and thrive.

For example, a provision in the OTA law requires big companies to pay a third of a project’s cost if they fail to include nontraditional firms in a meaningful way. “If you don’t have a nontraditional as either the prime or as a significant member of the team, then there’s a cost-share requirement on the part of industry. Well, no industry organization—none of the big ones for sure—want to have to do any cost sharing,” Tuohy said, “so it incentivizes them to bring a nontraditional onto their team to do the project.” That helps lower the barriers of entry for these guys, he said, “because they know they’re going to get a shot at getting on a team.”

The process creates teams that never would have otherwise come together—teams that can get fast results.

A few years ago, Tuohy recalled, the Army came looking for a high velocity, more accurate mortar round to address a problem it was encountering in Afghanistan. They said, ‘We need something quick,” so we had an industry day to help figure out what the art of the possible was.” After the solicitation came out, ATI held speed-networking sessions and, 90 days after the solicitation came out, the government awarded six contracts to six teams, four of which were formed because of that speed-networking process. “The good news is that 18 months later, production rounds were being delivered to Afghanistan,” Tuohy said, “which is like the speed of light in an acquisition.”

SIMPLIFY IT

Part of what makes such fast responses possible is that the companies turn in white papers with explanations of their ideas rather than multi-volume proposals. “[The responses] might be as much as 10 pages, but most of them are a couple of pages, depending upon what the solicitation requirements are,” Tuohy said. The management organization gathers the responses and works with the companies to be sure their submissions are formatted and complete. They then turn the papers over to the government. Timelines vary but getting a response in two to six months appears to be a reasonable expectation.

Once a deal is made, the contract is negotiated between the company, the government and the consortium manager. In many if not most cases the firm bills the consortium manager, which bills the government. The manager gets a small fee, covered by the government, for expenses and federally-mandated bookkeeping. Consortia staff also can act as troubleshooters and advisers, especially for small firms that have little experience dealing with the government.

Consortium staff also may help firms with intellectual property (IP). A key characteristics of an OTA agreement is that the rights to the IP a firm brings to the table are negotiated with the government.

In standard government contracting, when you develop a product for the government, the ownership of the intellectual property at the core of the product is not as clear and usually isn’t defined. “It’s like the government owns it,” said Molly Donahue Magee, executive director of the Undersea Technology Innovation Consortium.

That is not the case in an OTA deal.

“If the government pays me to do [a prototype] for the government need, I obviously can’t sell that,” Magee said. “But my technology may also have commercial applications and so that allows me, through negotiation, to be able to take applications other than the DOD’s that are based on that same technology and stay with the company to develop it further.”

Magee and her team mentor firms on IP and other issues “and where we can’t provide the exact support, we have a network that can give [support) to them. That is absolutely in our mission, because, again, it’s really that first time dealing with DOD, and in some cases, it’s the first time dealing with IP independent of DOD. And how do you protect that?”

OPPORTUNITY KNOCKS

Opportunities that emerge from the OTA process can pop up in unexpected ways. For example, groups within DOD, even if they are from other services, can fund projects through a consortium. The Marine Corps Systems Command, which is part of the Navy, has an OTA agreement with the Consortium for Command, Control and Communications in Cyberspace, also called C5. The Air Force, however, has been a very big funder of C5 projects.

This flexibility is good for everyone involved, noted Charlie McBride, chairman and CEO of CMG, C5’s management group. The companies benefit from having more money in the group for projects, the increased level of activity makes C5 more attractive to new members and the Air Force gets access to the expertise it needs. The OTA agreement also mandates that any project funded through the Marine Corps’ agreement by other DOD organizations has to “demonstrate that it has a short term or long term use for the Marine Corps itself,” McBride said, so the Marine Corps System Command benefits too.

Outside funding can also pop up as a second chance for a previous proposal. After a white paper is submitted, the government reviews it and has three choices, Magee said. “They can say, ‘Hey, we want that.’ And it goes a little bit further into establishing that formal other transaction. They can say, ‘No, sorry, it doesn’t meet what we need.’ Or, with the third alternative—which is pretty powerful—they can say ‘We’re going to put that ‘in the basket.”’ The basket provision allows the government to go back anytime over the next three years and pull that proposal out and award it without any further competition.

“If some other sponsor has a need and sees that that solution can meet their need, they can go in and pull it, too,” Magee said.

A CASE IN POINT

OTA also enhances cross-pollination between the services. PURVIS Systems, which works primarily for the Naval Undersea Warfare Center, recently won a deal to use its expertise in undersea sensors to find a solution for the Air Force.

The Air Force was having to limit its testing of sound pressure on airplanes because the sensors were getting wet, said Debbie Profit, vice president of DOD operations and business development for PURVIS. “So one of the Naval Undersea Warfare Center engineers manages some testing efforts for the test research management group down in Washington, D.C. One of his areas is testing technology. So he was aware; he got connected to this customer and knew that there was a requirement—so he had the ability to put the topic in the OTA.”

As a result, PURVIS is working with a local university and a five-person firm called Nautilus Defense to develop alternative sensors, including fabric-based sensors and/or coatings for the current sensors to solve the problem. “We’re really outside of what we normally do.”

This is exactly what PURVIS was hoping for when the company joined its first of two consortia a year and a half ago.

“We are only about 130 people,” Profitt said, “and it was a resource and an avenue for us to do additional technology work outside of our standard paths. So, primarily we do services contracts as opposed to product development, and OTA gave us an easier avenue to look at R&D and technology and more product-oriented work.

“It’s kind of neat,” she said, “and hopefully we can leverage it into other work.”