It appears the drone war between the United States and Iran won’t end with last month’s loss of a U.S. Navy RQ-4A to Iranian air defenses. If anything, the war is expanding, with the U.S. downing two Iranian drones and British drones possibly joining in after Iran illegally seized a British tanker. What can we expect from a drone war in the Persian Gulf?

The first thing is, it won’t be a “Drone War,” at least in the initial stages. The drones won’t fight each other but they will do tasks that manned aircraft either can’t do efficiently or find too risky. Drones will provide vital intelligence and occasionally employ weapons and relay communications. It will be a “War with Drones,” unless the U.S. arms its drones with air to air weapons—something I strongly suggest.

THE U.S. DRONE LINE-UP

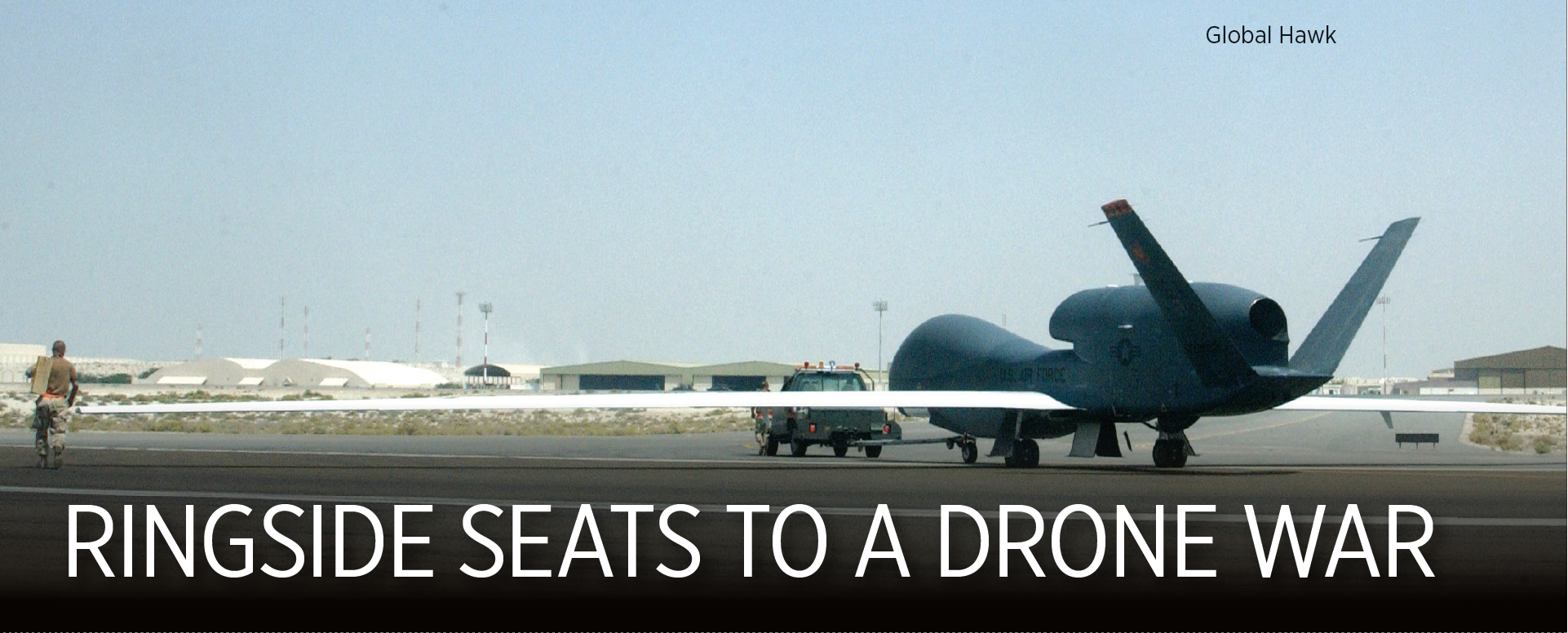

American drone operations will be much like what we’ve seen since 9/11, but in a maritime environment. America will use an array of large drones. The General Atomics MQ-9/Reaper, along with Northrop Grumman’s RQ

-4B Global Hawk and MQ-4C Triton, will fly most of the missions, but the smaller, ship-borne Boeing Insitu MQ-27 Scan Eagle and Northrop Grumman MQ-8 Fire Scout will play significant roles supporting U.S. Navy surface vessels. The U.S. needs either large long-endurance, land-based drones or shipborne drones because it will play defense in the Gulf.

Persistence will be the key to U.S. drone operations. The U.S. can never be sure wherean Iranian attack will come from. Iranian drones, small boats or missiles could strike within minutes from dozens of locations as ships transition the Strait of Hormuz. Tankers from Kuwait must travel 500 miles to the strait and Iranians could strike anywhere along that route from hundreds of locations.

Persistence will be the key to U.S. drone operations. The U.S. can never be sure wherean Iranian attack will come from. Iranian drones, small boats or missiles could strike within minutes from dozens of locations as ships transition the Strait of Hormuz. Tankers from Kuwait must travel 500 miles to the strait and Iranians could strike anywhere along that route from hundreds of locations.

Luckily, persistence is something American drones do very well. The USAF has mastered the art of keeping MQ-9s and RQ-4s on target continuously for weeks, or even months, at a time. The USAF flies both aircraft via “remote split operations” (RSO). Crews deployed near the Gulf launch the air vehicle using its line of sight data link and then hand the vehicle over to crews in the U.S. using a beyond line of sight (BLOS) satellite link. Keeping a drone on target is simply a matter of delivering refueled and rearmed air vehicles whenever a drone runs low on fuel or weapons. Baghdad had an MQ-9 overhead continuously for about seven years using this technique. The Navy has been flying its RQ-4As and MQ-4Cs RSO as well.

Unfortunately, neither the USAF MQ-9 or RQ-4 is specifically designed for maritime operations. The MQ-9 could easily become a capable maritime drone with the addition of a maritime mode for its Lynx Synthetic Aperture radar. General Atomics has just started installing Lynx radars with modifications that will allow crews to detect Iranian vessels at long range and slew the electro-optical/infrared sensors on to the target. The USAF also plans to mount Lockheed’s Joint Air-to-Ground Missile (JAGM) on the MQ-9. The JAGM is a “fire and forget” missile that crews can ripple launch against multiple targets after designating them with a laser or radar. This will be the perfect weapon against swarming Iranian small boats.

The MQ-4C, MQ-27 and MQ-8 were designed from the ground up as maritime drones and will be extremely useful in this conflict. The MQ-4C Triton is based on the RQ-4 Global Hawk but is a much more advanced drone than the USN RQ-4A Iran shot down last month. The Navy has been silent about MQ-4C electronic defenses, but they are probably much improved over the RQ-4A. The MQ-4C has a long-range EO camera, an airborne electronically scanned array (AESA) radar and classified electronic sensors that, combined with airframe improvements over the Global Hawk, will allow it to either loiter above 55,000 feet to cover a large area or dart down to a few thousand feet to get high resolution imagery of targets. The fixed-wing MQ-27 Scan Eagle and rotary-wing MQ-8 Fire Scout will provide coverage around their parent ships. Neither aircraft has a BLOS link like the Triton’s, so they must stay within range of their shipboard control stations. Hence, the Triton will provide wide area surveillance data to individual ships that will then launch their Fire Scout or Scan Eagle to identify and track contacts as they get close. Unfortunately, again, none of these Navy drones are armed, which will force the Navy to use armed USAF MQ-9s, manned aircraft or shipborne weapons to engage targets.

All U.S. drones mentioned here are very difficult to counter with jammers. The details are classified, but they either use a very powerful directional data link or a combination of advanced link algorithms and autonomous flight software to counter jamming.

THE IRANIAN STRATEGY

Iran will approach this War with Drones very differently from the U.S. Although Iran claims to have a large, long range drone like the MQ-9 (the Shahed 129) and a copy of the USAF RQ-170 stealth drone (the Shahed 171), it doesn’t employ either drone in large numbers. The Shahed 171 is more of a publicity stunt than an operational drone, and the Shahed 129 had a series of reliability problems that limited combat time over Syria supporting Iranian proxies.

Iran’s strength lies with its small drones and the years of combat experience gained fighting with them over Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Gaza and even Israel. Iran’s Ababil and Mohajer drones will never win any design contests but they have been very effective, operating over even Israeli air defenses since the late 1990s. The designs are minimal; even the most sophisticated Ababil-3 is made from fiberglass and plywood, with a Chinese knock-off two-stroke engine copied from a German design. The Iranians’ most widely used drone, the Ababil-2, looks like a model airplane and sources most of its components from the internet.

Iran’s strength lies with its small drones and the years of combat experience gained fighting with them over Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Gaza and even Israel. Iran’s Ababil and Mohajer drones will never win any design contests but they have been very effective, operating over even Israeli air defenses since the late 1990s. The designs are minimal; even the most sophisticated Ababil-3 is made from fiberglass and plywood, with a Chinese knock-off two-stroke engine copied from a German design. The Iranians’ most widely used drone, the Ababil-2, looks like a model airplane and sources most of its components from the internet.

But the crude designs of Iranian drones belie their effectiveness and their ability to elude allied air defenses. I remember talking with an Israeli Air Force friend after an IAF F-16 finally shot down an Ababil in 2006. “The most expensive shoot-down in Israeli history,” he called it, because it took multiple F-15 and F-16 sorties to finally bag the Ababil. The USAF was only marginally more successful, with it taking an alert scramble of two F-16s to down a single Ababil in 2009. Iranian drones have been used to great effect against targets as diverse as Saudi Patriot missile radars, a military parade in Yemen, and airports in Saudi Arabia and Yemen.

Iran can get away with deploying these small drones for reconnaissance and strike missions because they’ll remain as clandestine as possible while playing offense. Iran doesn’t need a Global Hawk that flies for 30+ hours because it will choose where and when to strike. Most of the conflict will be in the Strait of Hormuz, placing the action within 20 miles of Iranian territory. Iran can watch for allied ships from land, confirm their identity with a 30-minute drone sortie and have strike drones on target minutes later. Its combatants will probably mount Mohajer on small dhows to mix in with the hundreds of fishing vessels in the Gulf and extend the attack range. None of these drones will carry Iranian markings and, if caught in the act, its forces will either blame it on terrorist proxies or claim the drone malfunctioned. Also, these drones will be hard to detect and even harder to shoot down. The Allies’ best hope will be jamming data links, but Iran can also program its drones to fly autonomously.

ROLE BRITANNIA?

British drones will be an interesting addition to the mix if the Brits decide to deploy more forces to the Gulf. Most folks think the Israelis are our most drone-savvy ally, but the Brits have been very canny in developing their drone forces. Rather than building lots of home-grown drone designs largely employed close to home, the Brits let the Americans solve all the tough problems needed to deploy their drone forces on a global scale. The Royal Air Force (RAF) was the first—and only—American ally to fly the General Atomics MQ-1 Predator via RSO alongside U.S. Air Force personnel at Creech AFB, Nevada. When the USAF upgraded to the MQ-9 Reaper, the RAF bought several MQ-9 aircraft that it operates as a pool with USAF MQ-9s.

In 2012, the RAF set up its first dedicated MQ-9 squadron in the UK with the ground control systems and data links needed to fly independently from the USAF. By then, the RAF had begun to improve its MQ-9s with a series of UK-specific modifications that led the MoD to eventually buy the much improved MQ-9B SkyGuardian. Unlike the USAF MQ-9A, the SkyGuardian meets British and American civil aviation airworthiness standards, meaning it can fly integrated with even civilian manned aircraft. It has a much longer range, adverse-weather features and carries the MBDA Brimstone missile—another weapon that can ripple fire against multiple moving targets.

All these changes have given the RAF a drone force that would be better suited for maritime combat than American MQ-9s in a prolonged contest with Iran—at least until the American drones get the modifications I mentioned. Although the longer range and civic airworthiness of the MQ-9B are important, the real differentiators are the all-weather capability of the MQ-9B and the Brimstone missile. The MQ-B is protected from lightning, has anti- and de-icing gear, and is provisioned for weather radar. Unlike the AGM-11

4 Hellfire missile on the USAF MQ-9, the Brimstone doesn’t need the crew to continuously track a target to hit. The Brimstone’s “fire and forget” capability makes it the perfect counter to Iranian swarming small boats.

MQ-9 with Hellfire

Like the U.S., the RAF can fly its MQ-9s via RSO, with pilots stationed elsewhere. The Brits have several strong allies in the Persian Gulf, but I’ll bet that either Oman or the UAE would be their choice to base MQ-9Bs. Look for the RAF to station an armed MQ-9B right over the strait whenever British tankers transit. It will be a nasty surprise for the Revolutionary Guard.

With any luck, I’m dead wrong about an extended War with Drones over the Persian Gulf. I hope our diplomats are working out a solution as I write this and the world won’t have to worry about another Gulf War. If I am correct, we’ll see drones in action up and down the Gulf. The Americans and Brits will be on the defensive with their superbly designed long-range drones, and the Iranians will be on the offensive with drones that could have been built in a garage. The irony is that both approaches will work.

MQ-9B with SkyGuardian