Autonomous Contenders Vie for the XPrize Foundation’s $10 Million Rainforest Competition

“Measuring spatial density of trees—it’s something I train my students to do by hand. We walk around and we measure the distance between trees. Now I can just fly in the air and, snap, sit at the table using a computer. The ecologists of the future will measure organisms in space and time so much more effectively.”

Tropical ecologist Dr. Tom Walla of Colorado Mesa University has been sampling and quantifying biodiversity in the upper Amazon for more than 25 years. Now his multi-university Team Waponi is one of six finalists for the $10 million XPrize Rainforest competition, to be awarded in July 2024 after a flyoff in Brazil.

Welcome to the Jungle, another finalist using wide expertise, is led by mechanical and aerospace engineering Prof. Matthew Spenko of Illinois Tech (Illinois Institute of Technology). “I’m not really a Guns N’ Roses fan, but I think it hits where we’re going,” Spenko said about using the name of that band’s song. This team is using biometric/imagery sensors and 3D mapping to investigate tree-species diversity without leaving any inorganic material behind. Inside Unmanned Systems spoke with the team leaders to learn how their solutions might solve one of what the XPrize Foundation calls “humanity’s grand challenges.”

X-PLORING THE CANOPY

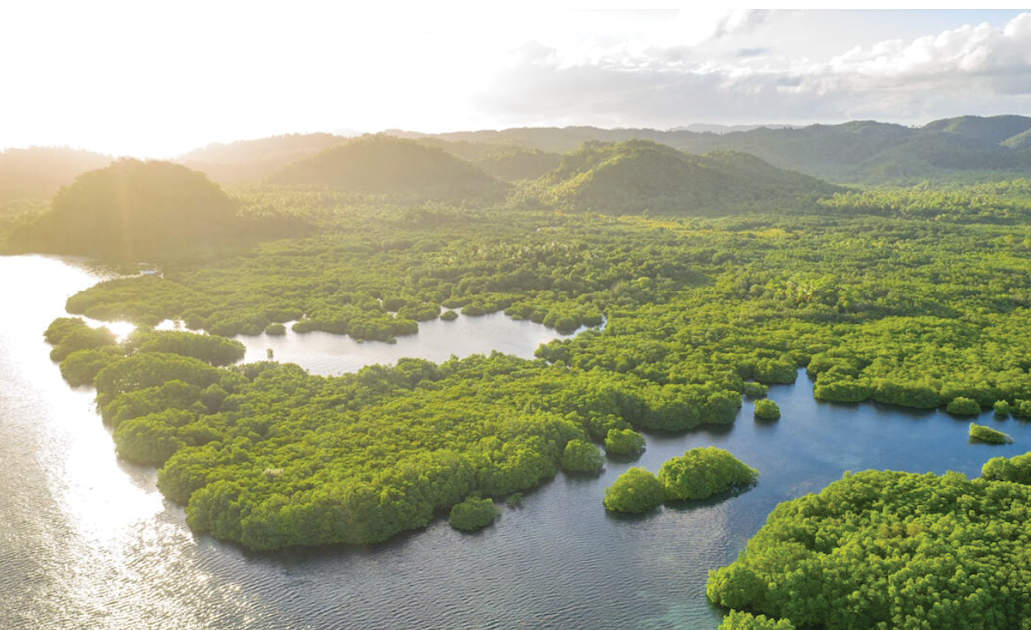

Founded in 1994, the XPrize Foundation’s multiple competitions are about “incentivizing crowd-sourced, scientifically viable solutions to create a more equitable and abundant future for all.” Launched in 2019, the five-year Rainforest quest seeks to furnish what Amazon Watch board president and XPrize judge Atoosa Soltani called “serious intervention to halt rainforest destruction.”

Sixty teams answered XPrize Rainforest’s call for scalable technology to “measurably improve biodiversity monitoring” through “autonomous and rapid data integration that provides unprecedented levels of details in real time.”

This past June, six drone-enabled entrants emerged from a 13-team, 24-hour-in-the-forest technologies test held in Singapore. Within 48 hours, they’d surveyed and captured data and physical samples to provide a “species-richness assessment.” Explorations ranged across eDNA, sampling, biometric sensors and canopy monitoring. As Peter Houlihan, the executive vice president for biodiversity and conservation at XPrize, put it, “We cannot effectively protect what we cannot accurately measure and understand.”

Brazil’s 2024 finals will involve surveying about 250 acres of tropical rainforest in 24 hours and producing real-time, scalable insights that, the XPrize Foundation hopes, can “effectively disrupt the current biodiversity assessment landscape.” The winner will excel at analysis, execution and impact.

“They’re very concerned with the health of the rainforest itself and the health of the planet,” Spenko said of the foundation. “They’re good at identifying areas that may not receive the type of government or corporate funding that is necessary to make advances. They’re pretty hands-off. They’re more the accelerant.” But, he said, “they want a product at the end of this.”

CONVERGING ON DRONES

Spenko and Walla come from different backgrounds but converge on using drone technology for rainforest data analysis.

Spenko hails from the technology side. “I’ve always tried to focus on mobility and challenging environments,” he said. “I worked on my post-doc on climbing robots and then transitioned into multimodal robots that could both fly and have terrestrial locomotion.

“I’ve had a side interest in ecology, and it’s sort of melding with robotics and field work,” he said. “We focused early on drones because I have enough experience in ground robotics to understand that it’s not a tenable solution for the rainforest environment. It’s too dense.” Spenko wouldn’t divulge his team’s “secret sauce”—”let’s just say we are deploying and retrieving sensors throughout the rainforest.” The Jungle team also is drawing on AI species identification by Kenya’s Natural State Research Centre.

Walla was happily collecting caterpillars—”Waponi” is an all-purpose greeting in the language of one of Ecuador’s hunter-gatherer tribes—when he embraced drones. “About two-and-a-half years ago, it just took off,” he said, no pun intended. “I began calling and learning about drone technology and new DNA and machine learning technology.”

Today, Walla wants “to figure out a way to bring intact tropical rainforest into the economy so that it can be valued and protected. Right now, there is no easy way to place a value because there are too many species to count, too many interactions to understand.

“How do we find that universal biodiversity currency? What does that look like?” Walla asked rhetorically. “This is an opportunity to take our experience and really expand its impact in what could potentially be a global scale of helping indigenous people get training for technological fields and collecting their own data and help them stay sustainably in the forest.”

INTO THE WOODS

Walla’s drone exposure involved some trial and error. “The first drone that I bought was a [DJI] Mavic 3, which was pretty sophisticated. My second drone was an M600—I crashed that in the field behind my house.” But he soon was all in on UAS potential: “It was like someone dropped the Easter Bunny on my porch. I thought, ‘Here it is. This is your chance to change the world.’”

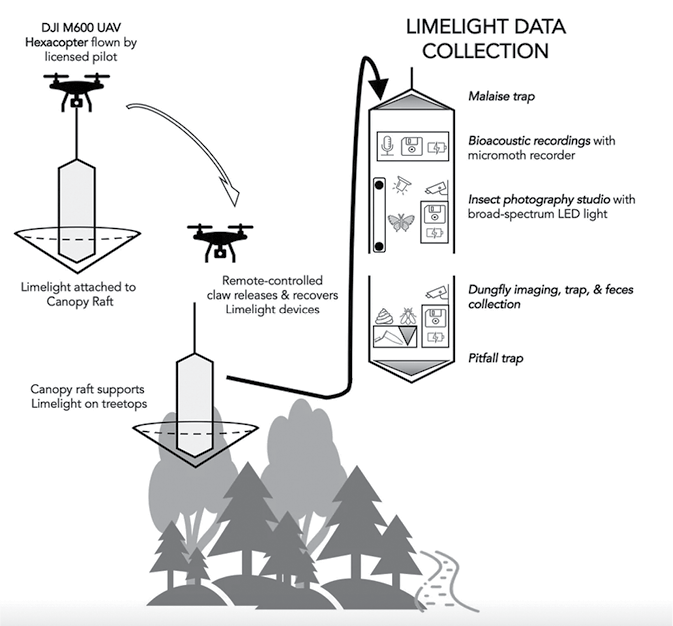

Walla’s conclusion that a hovering drone couldn’t connect to a fixed object in the tree canopy led him to Outreach Robotics of Sherbrooke, Quebec. Outreach could dangle a device under a drone to deliver a data collection solution called Limelight into the canopy. Limelight then could collect bioacoustic data and insect images and specimens for classification through machine learning.

The cylindrical Limelight contains insect traps and recording sensors, and an insect-attracting “photography studio” complete with LED light programmed at the New Jersey Institute of Technology using Raspberry Pi. A remote-controlled claw attaches Limelight onto a supporting “raft,” which Walla described as “a series of carbon fiber poles with a center space about 50 centimeters on the diagonal where you could put any kind of collection device.” The claw releases and recovers the Limelight devices; once retrieved, researchers from Virginia Tech handle much of the resulting DNA identification and classification.

“We have, with drones and the cameras, an incredibly fast way of collecting large amounts of data that you just had to ignore before—it was just too much,” Walla said. “Now, using AI, Instead of taking a sample of things, you can just count them all.”

SINGAPORE’S SEMI-FINALS

For the semi-finals, Team Waponi’s Limelight system was successfully deployed by personnel from three universities and two Outreach flyers. “We were right next to another team and we each had our square-kilometer plots,” Walla recalled. “The other team was about a quarter mile away and we shared a ranger station for analysis.”

In Singapore, Spenko’s Welcome to the Jungle team included faculty and graduate students from Illinois Tech and Purdue University, the latter leading aerial surveying to measure vegetation through multispectral and natural color imagery. Purdue participants also determined potential sensor deployment locations.

Jungle went for an off-the-shelf basic drone, a DJI Matrice M210. “We didn’t have the funds, so we went into Singapore blind,” Spenko said. “There were a couple of big surprises. One was how much the density of the jungle affected our radiocommunications.” Jungle had flown at the Chicago-area Morton Arboretum—“we’re at 1.2, 1.3 kilometers, great signal, and maybe we’ll lose half of that. We got down to Singapore, max maybe 150 to 200 meters out. We’ve been testing a bunch of different solutions to see if we can get our range back out to about a kilometer.”

Walla reiterated the hurdle. “We now have to get our drones to fly further. The greatest challenge is standing on the ground in a rainforest, it’s 150-feet-thick of trees, trying to fly a drone a kilometer-and-a-half away across that canopy and down into a tree fall gap. The radio waves get sucked up by the trees.”

BRAZIL AND BEYOND

Teams won’t be able to rest on any tropical laurels for the finals, as the Brazil site will lack internet, electricity and cell connection.

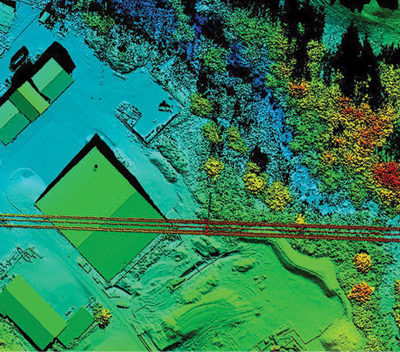

LiDAR and RGB may come into play for Team Waponi’s canopy measurement, Walla said. “You can do that autonomously. We have some ideas for solving the drone distance problem that I can’t really share.”

The Jungle team will use two DJI M350s, as the 200 series is no longer supported.

“Our Purdue partner,” Spenko said, “will use LiDAR to map the area. But for us, it’s just the RF signal from the operator to the drone. Purdue is pretty much autonomous; our solution is mostly teleoperated. We’re working on some autonomous components—for the XPrize, they want something as autonomous as possible. We’re flying in tight areas, non-line of sight, on a budget. We have to be pickier on what we can do and where we want to deliver the sensors. We’re working toward a solution that will autonomously pick the sensors back up.

“The overarching goal is to develop insights about this track in the forest,” Spenko added. “We want to understand biodiversity, whether there are invasive, new or undiscovered species in that particular area, and if there’s been any disruption in terms of logging or things like that. It’s a little broad, but in general what the XPrize Foundation is looking for are insights into the health of this rainforest.”

Walla concurred: “XPrize believes there needs to be an automated or semi-automated data collection procedure to make it standardized and reliable.” Spenko echoed Walla’s call for drone use by the indigenous peoples themselves.

“They don’t want a bunch of Western scientists going in saying, ‘You got $250,000, you can buy these things.’ I think it’s more about creating tools that can be readily available and useable by people who are actually living in these environments.”

Walla summarized the competition’s overarching autonomous benefit. “I think there’s some amazing potential for what drones can do for ecology. We measure space, and we measure organisms in space over time. And I just think that the drones provide this incredible opportunity to improve the way we do that.”