The FAA will undoubtedly require UAM drones to “squawk” (broadcast their ID and position) via drone remote ID gear as well as manned aircraft ID such as Automatic Dependent Surveillance Broadcast (ADS-B) and transponders. After all, running into another aircraft is a real threat to drone UAM operations. It seems that, for once, industry and the FAA are seeing eye-to-eye on ensuring these drones behave themselves from the start.

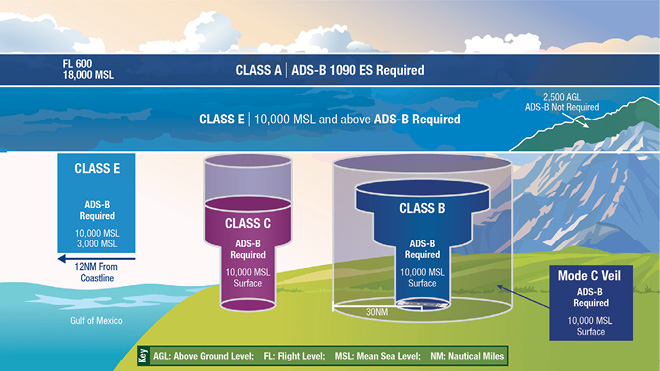

But is the FAA doing enough with manned aircraft to ensure that they’ll behave themselves when the sky fills with passenger drones? I’ll admit, I thought the FAA had solved this looming problem by making ADS-B “Out” equipage—which allows vehicles to broadcast their position, vector, altitude and velocity—mandatory in 2020 for all aircraft operating in airspace that now requires a Mode C transponder (Figure 1). Requiring all aircraft to squawk via ADS-B would radically cut the risk of drone taxis running into manned aircraft because they’d both have ADS-B and could therefore sense and avoid each other.

Unfortunately, I concentrated on the “ADS Out mandatory for all aircraft” bit and ignored the “operating in airspace that requires a Mode C transponder” piece. That’s a lot of airspace around the United States that won’t require manned aircraft to squawk, meaning that drone taxis won’t be able to sense and avoid them via ADS-B. Catching a drone Uber to an Aggie game? Watch out for silent manned aircraft. Want to drone up to Breckenridge for some skiing? Bring binoculars; not everyone has to squawk up there.

What’s more, manned aircraft without electrical systems won’t require ADS-B. That’s ultralight aircraft, antique aircraft and a disturbing percentage of crop dusters. ASSURE lead Mississippi State University did a survey of crop dusters operating in the Mississippi Delta and found that 30 percent of the aircraft had no electrical system. Compliance is another issue. An FAA study found that just six months out from mandatory ADS-B compliance only 44 percent of general aviation had installed ADS-B Out equipment.

AN AIRBORNE RX

HERE’S WHAT I THINK THE FAA SHOULD DO:

Manned aircraft must squawk—everywhere: The FAA, unfortunately, chose to make ADS-B equipage part of regulations pertaining to airspace and not an aircraft rule, meaning ADS-B isn’t part of the basic airworthiness of an aircraft and is only required to fly in specific airspace. The FAA has always approached navigation equipage as an airspace issue and not as a basic flight safety issue because the bedrock of the FAA’s safety system is the pilot’s ability to see and avoid other aircraft—if a pilot can do that, why must every aircraft have ID gear to avoid collisions? Shouldn’t they only need it in congested airspace?

As a result, the ADS-B mandate came about as an aid to air traffic controllers providing flight separation services to aircraft in controlled airspace and not primarily as an augmentation to pilots looking to avoid collisions on their own. This thinking affected how the FAA set up airspace for small drones in its Part 107 rules. Drones were banished to the Wild West of American airspace—flight below 500 feet outside airport airspace where the FAA had never regulated, and every aircraft—manned and unmanned—had to rely on its own eyeballs to avoid collisions.

It’s becoming clear that this is an unworkable solution even today, before we have passenger drones. The FAA’s drone rule-makers are hard at work fixing this problem by making drone remote ID equipage mandatory in all airspace and creating an automated Unmanned Traffic Management (UTM) system that will use drone remote ID and computers to avoid collisions, not human eyeballs. This system would be much, much safer than a visual system if it wasn’t for the very real possibility of drones encountering manned aircraft without ADS-B.

To solve this problem, the FAA should make mandatory ADS-B equipage part of its aircraft and not airspace rules. It should do away with the notion that ADS-B exists to make controllers’ lives easier in avoiding collisions and replace it with the idea that ADS-B is there to save lives by making pilot’s jobs easier to avoid collision. It’s taken 15 years to get to mandatory ADS-B equipage for aircraft in controlled airspace, so it’s not too early to start preparing for the radical air traffic increase UAM and other beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) drone operations will bring by making all aircraft—manned and unmanned—squawk their position in all types of airspace.

Manned aircraft must hear squawks—everywhere: In keeping with the notion that squawking is to make controllers’—and not pilots’—lives easier, the FAA only mandated ADS-B Out by 2020 and has not mandated ADS-B In equipage. Again, ADS-B Out simply transmits an aircraft’s position, vector, altitude and velocity for controllers to track the flight. With ADS-B “In” capability and a compatible cockpit display, pilots can use this tracking data to see the other aircraft traffic targets in the vicinity. Essentially, pilots could then view the same traffic data that controllers monitor on their scopes. The safety advantages are obvious—pilots with ADS-B In will still dutifully see and avoid collisions with other aircraft. But with ADS-B In they’ll also see an order of magnitude more potential collisions than they could with eyeballs alone.

The problem that prevents mandatory ADS-Out equipage from making the skies safe for UAM is that the FAA probably won’t allow drones to use ADS-B Out to broadcast their position. True, the drone remote ID draft rules aren’t out yet, but I’d be shocked if the FAA picks ADS-B for drone remote ID. FAA Air Traffic has always been against using ADS-B because they think it will saturate the ADS-B broadcast frequency. Hence, drone remote ID broadcast will probably be via either LTE, Wi-Fi or Bluetooth and ADS-B In equipment that won’t hear drone squawks. Will aircraft owners willingly pay more for drone remote ID receivers, particularly since many are getting ADS-B equipment just before the deadline and would have to buy another set of gear just to hear drone ID squawks?

The drone community (and its FAA regulators) understand this problem and is designing UTM with drone remote ID and ADS-B In as an integral part of collision avoidance plans. Unlike manned aircraft that may not even carry drone remote ID receive equipment and don’t have to equip ADS-B In, remote pilots using UTM will have an integrated display of all traffic around their aircraft with software that helps them avoid collisions.

It will cause a howl from the general aviation community, but the FAA should mandate ADS-B In and drone remote ID equipage that includes a cockpit display capable of displaying traffic in all aircraft. The FAA should also work with industry to ensure UTM track display and collision avoidance capabilities are integrated with manned aircraft ADS-B/drone remote ID displays. This is a tall order—it’s one thing to make a Stearman biplane carry a battery-operated ADS-B Out system because the Stearman doesn’t have an electrical system. It’s quite another to make Stearman owners integrate an ADS-B In display in their cockpits.

However, it’s the right thing to do. FAA BVLOS rules are coming soon and that will fill the skies below 500 feet with package delivery and imaging drones. That’s going to make flight more dangerous for helicopters and all those aircraft without electrical systems: ultralights, kit planes, etc. However, BVLOS rules aren’t going to include unmanned taxis—yet—so the current danger involves collisions between manned and completely unmanned aircraft.

UAM will change this equation. UAM drones will fly under 500 feet with other drones, in controlled airspace with ADS-B-equipped manned aircraft and in airspace that doesn’t require manned aircraft to squawk. It would be simply unacceptable to put the lives of UAM drone passengers at risk because the FAA didn’t mandate proven, effective anti-collision equipment for all aircraft.

The FAA would do well to remember the incident that prompted its creation: the 1956 mid-air collision between two passenger aircraft in uncontrolled airspace over the Grand Canyon that killed 128 people. Both were flying visual flight rules, supposedly seeing and avoiding each other. Neither did. Ironically, the Grand Canyon is one of those “no ADS-B required” spots where manned aircraft don’t have to equip ADS-B as long as they stay below 10,000 feet. That’ll be prime airspace for UAM drone tours.