The Chula Vista Police Department is testing centrally dispatched, remotely piloted drones as a tool to expand and better prioritize responses to calls.

The police department in Chula Vista, California, is pushing the cutting edge. If successful, it will help nudge the boundary of where drones can fly past the limits set by what a pilot can see,toward a future where drones can simply go where they are needed, no matter the operator’s location.

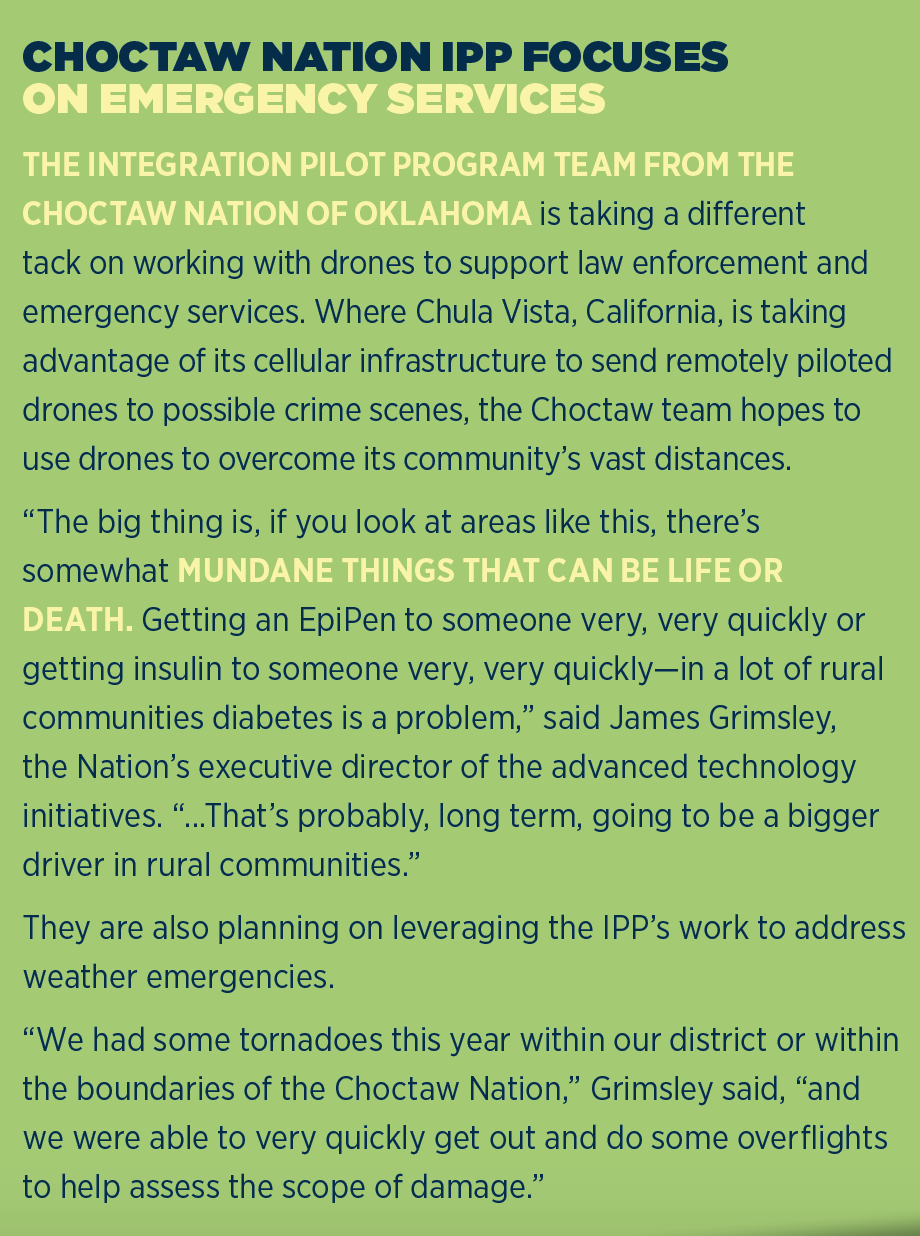

The city is a member of the San Diego Integration Pilot Program (IPP), an effort supported by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) that aims to tap the creativity of industry, local governments and the public to test new drone applications. The three-fold goal is to prove the value of drones to the citizenry, hammer the kinks out of real-world operations and speed the integration of unmanned aircraft into the national airspace by using IPP test data to fuel rule-making.

Chula Vista is not the first

municipality to give drones to its police force, but it is breaking new ground with its approach. Many jurisdictions have officers cross-trained as drone pilots who carry unmanned aircraft in their cars for use as needed. Chula Vista has deployed drones that way, but is also dispatching drones from the roof of its police headquarters and flying them remotely.

COMMAND CENTRAL

Operating those new unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) is a trained police officer who’s also a qualified drone pilot. That person is based in the watch commander’s office, with a flight computer and a monitor showing all the predefined areas where they’re allowed to fly. If a report comes in from one of those areas, and it would be beneficial to have a drone at the scene, the officer/pilot will launch and teleoperate the drone from his or her desk.

The police pilot at the keyboard works with a civilian pilot on the building’s roof who scans the skies before and after takeoff to be sure no other aircraft are in the area. The drone will already have had a preflight check and is ready to fly so there is no delay. So far, on average, the drones have been arriving at the scene in just over two minutes.

“That teleoperator will get the drone over the scene and start to feed information via the radio to our officers,” said Vern Sallee, the captain in charge of the police department’s operations division. “They’ll give them critical information that they can see.”

For example, Sallee said, if a caller reports a person at an intersection acting erratically and carrying an object, the teleoperator can quickly dispatch a drone and use a zoom lens on the aircraft to determine what’s being held. With the right angle and altitude, it’s possible to see if it’s a cell phone, a knife or a gun—information the pilot shares with the officers headed to the scene. “[They can] also tell them what the person is doing, the exigency that they’re facing,” Sallee said. “Is this person away from the public or is the public in danger? …If nobody’s in immediate danger, we can slow down and make better plans so that we have better outcomes.”

In at least one recent case, the ability to send a drone made the difference in deciding to send officers to an escalating incident.

A seemingly routine initial report came in when there were no officers to send out—but a drone was available, Sallee said. “The 911 caller did not give us much information and when the drone got overhead we could see essentially a female in a car trying to run over her boyfriend on a motorcycle—[she] tried to ram him several times.”

Chula Vista’s drone team was instrumental in identifying the deadly seriousness of a seemingly routine call and getting officers on the scene before a driver succeeded in ramming a cyclist.

“As the drone arrived, the confrontation escalated from a couple fighting to a high-speed pursuit with the drone tracking it from above,” said Kabe Termes, the director of business operations and regulatory compliance for Cape, which makes the teleoperator software. “They were blowing through red lights and stop signs, and driving on curbs, and the person in the car was trying to actively run the motorcyclist off their vehicle. They were able to track them until the suspects came to a stop and then triangulate all the officers around them so that they could swarm and make the arrest.”

CAPE CONTROL

The Cape software is added to the flight computer and requires no hardware changes to the drone. It can also transmit video to mobile devices, enabling cloud-based sharing of video with up to 50 cell phones and other devices.

Headquartered in Redwood City, California, Cape was originally a video-for-hire service that was going to be centralized at U.S. ski resorts. That evolved into transmitting drone video over the internet, and then operating the drones remotely via the cloud. Before signing on with the IPP program, the firm honed its technology during an eight-month pilot project in Ensenada, Mexico, where it flew more than 2,500 missions.

The system relies on servers hosted by Amazon Web Services and uses encryption on par with that for online banking, Termes said. To make it work, however, internet connections and the network have to be up to speed.

“Luckily, our requirements aren’t that strict. It’s about five [megabits] up and down and 100 millisecond ping [an indicator of latency], which is provided by most LTE connections out there—that’s worldwide at that point,” Termes said, “and then most Wi-Fi [systems] are able to achieve that as well too.”

As for how far away the pilot can be, there’s no limit as long as the total latency—the time for a command to go from the operator through the ground controller to the cloud to the drone and then all the way back through again—takes 500 milliseconds or less.

“You can be on the other side of the planet or you can be in the same room,” Termes said. “It’s all just based on internet speed.”

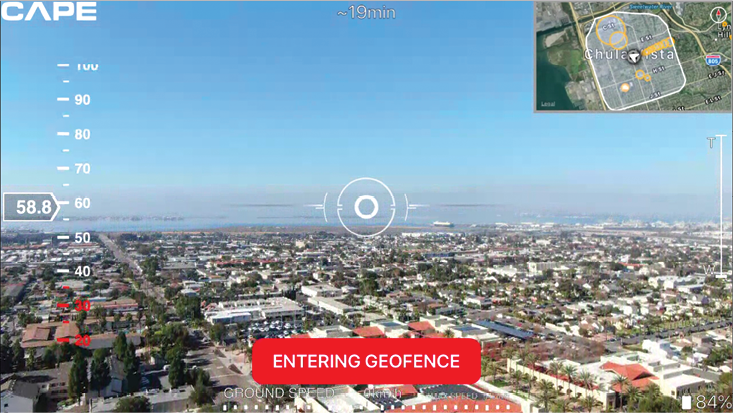

The Cape software also incorporates a number of safety features, including having the drone return automatically to the launch point if connectivity is lost or if available battery power drops too low. To keep the police department fully in the loop, Cape developed a phone app that issues a notification whenever there’s a flight, Sallee said. The software also has substantial geofencing that keeps the drones from flying too high (above 500 feet), too low (below 200 feet) or out of bounds. It also helps limit crashes by geofencing out obstacles like trees, buildings and other, more unusual, risks to flight.

For a time, an apartment complex was being built near the police station, and there was a very tall crane on the site, Sallee said. “For about two months, we had to geofence out that crane so that we could make sure that we avoided that.”

(UPPER) What the Cape flight monitoring screen looks like. (LOWER) One of the drones used by the Chula Vista Police Department.

WHAT’S NEXT?

Sallee said the department would like to expand from the current schedule of flying 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Monday through Thursday to providing coverage dawn to dusk, seven days a week. Eventually, as they get more confident with the technology, they would like to begin testing night flights.

What is holding them back right now is funding, which Sallee estimated at about $150,000 so far—though, he added, that included start-up costs. “We don’t have a line item budget for this—and it’s a pilot program.”

Chula Vista has also already applied to the FAA to establish a second remote location two to four miles from the police department. There would be another pilot on the roof there who, like the first, keeps the drone in sight at all times and has the ability to land the aircraft if, for example, a medical helicopter suddenly appears.

There would not, however, be another teleoperator.

“We would be able to fly either drone using the same teleoperator. So there would be an economy of scale. That concept is called one-to-many—one operator to many drones. We’re dipping our toes into that.”

(UPPER AND LOWER LEFT) The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma IPP team is using drones to assess tornado and flood damage. (RIGHT) The Chula Vista Police Department operates its drones from inside the police department.

Over time, Sallee said, as the technology matures and having visual observers on the roof is no longer necessary, the department hopes to pre-position drones throughout the city—for example, putting them on top of every fire station so they can get to any call for service in the city within two minutes and start feeding live video to officers.

It would take two or three pilots and nine or 10 launch sites, Sallee said, to provide services to the entire 50-square-mile city. Again, a key issue is finding a way to do it without observer pilots on the roofs.

“We need it to be far more automated. This model, the way we’re doing it, we can sustain it for now—but could we sustain it for years and years? That’s open for debate,” said Sallee. “…There’s a cost there to keep somebody on the roof for 10 hours and that’s what I talk about in terms of budgetary sustainability.”

That cost is offset somewhat by what Sallee deemed to be the program’s most surprising benefit—being able to clear calls without sending an officer to the scene.

“We’ve had calls of traffic accidents. We’ve had calls of objects in roadways or people in roadways,” Sallee said. They may not be that high a priority, or come in at a time when officers are more urgently needed elsewhere. “But if we get the drone overhead we’re able to actually assess, figure out what resources we need—or figure out if we don’t need any resources.” With a trained police officer as the teleoperator, he said, they can call the reporting party back or give the call a disposition without ever sending a ground unit. “So it’s a successfully resolved call—and we didn’t realize that we would have so many of those.”