Matt Lackey and the team at SAIN Associates, a surveying engineering firm in Birmingham, Alabama, invested in their first unmanned aircraft system (UAS) late last year. Many of their competitors were already using the technology, and they knew if they wanted to keep up, they’d need to do the same.

After doing some research, they discovered a fixed-wing system (what many of their competitors were using) just didn’t make sense on their sites, which are typically restricted, yet active, areas. They needed a smaller solution they could use on both small and large projects. Flight time was key and was one reason they decided to invest in the md4-1000 from Microdrones. Equipped with a high-resolution camera, this system allows them to complete a variety of tasks, including topographic surveys, American Land Title Association (ALTA) boundary surveys, dirt movement measurement and project tracking.

Lackey is focusing on photogrammetry for now, but does see the value in deploying more advanced solutions like LiDAR. “The last time I saw something like this come into the survey world where everybody was going to it was when survey grade GPS became available,” said Lackey, SAIN’s Project Manager Survey—UAS. “Now, it’s not a second thought. It’s just part of your equipment. That’s where this is heading really quickly. You really don’t have a choice but to do it.”

The construction industry as a whole is starting to see the advantages drones can provide, said Dmitri Alferieff, senior director of virtual construction for Associated General Contractors of America (AGC). In the early days, marketing was the most common use, but now the industry is finding much more advanced applications and are investing in many different systems. Companies are flying drones to create maps, monitor progress, improve safety, capture video and measure aggregates. They’re improving efficiencies and saving money and time, making drones an increasingly valuable tool for a variety of projects.

SITE MONITORING

CLAYCO, a Chicago-based construction firm, has been deploying UAS since 2014, mostly for documenting and monitoring, Vice President of Virtual Design and Construction Tomislav Žigo said. The company was ready to start automating more processes, and saw drones as an efficient way to consistently and efficiently collect aerial intelligence, as well as to automatically compare what is being executed on a site to the construction documents or plans.

“Construction sites are extremely dynamic environments, with changes happening in minute increments,” he said. “Documenting the site can be a daunting task, especially when collecting images on large sites that are hundreds of acres. Before drones, the consistency of collecting this information was always somewhat questionable. You’re primarily relying on somebody to walk the site in a consistent manner, and that just doesn’t happen.”

CLAYCO has used a variety of drones, including the DJI Phantom 4, the DJI Inspire systems and the DJI Matrice 200. The drone and sensors flown depends on the job, but the company is looking to standardize so every site uses the same system and delivers the data collected in the same way.

Mostly, CLAYCO focuses on analyzing orthomosaics created by stitching together thousands of images a drone collects as it flies in a lawn mower pattern over a job site. Žigo has found the greatest benefit coming from documenting underground utilities and excavation activity associated with burying equipment, conduit or underground pipes covered with concrete or pavement. He can overlay orthomosaics on original drawings to see if conduit is being laid as it should be, or if dirt is being moved according to construction plans.

CLAYCO is also using artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning to evaluate progress and visually monitor jobs for safety issues. While still in its early stages, thousands of images (captured by drones as well as other means) are being analyzed through a service called smartvid.io for safety infractions, such as incorrectly run equipment or exposed rebar. Machine learning recognizes a pattern in the photographs and extracts certain data to determine something is wrong, alerting management to issues. The company is also looking to use AI for visual schedule tracking to validate schedule execution.

Using drones to monitor site progress can keep stakeholders informed virtually.

“Global project teams need to understand progress on a project without visiting the site,” said Dave Henderson, Director, GeoPositioning Sales, Americas for Topcon Positioning Systems, headquartered in Livermore, California. “UAS can easily collect data and distribute with collaboration tools to assist those teams in making informed decisions. Drones also can be used to inspect structures in the area that were too difficult to access before or too time-consuming.”

Aaron Lawrence is technology director, unmanned systems for Dayton, Ohio-based Woolpert, a national architecture, engineering and geospatial firm. Recently, he found a major problem on an airport project via UAS data. The airport switched contractors on a runway extension between phase one and phase two of the project, and data captured from a UAS showed the second contractor hadn’t built phase two to spec—which was bad news for the job’s progress.

“There’s no way they would have been able to discover this problem efficiently with traditional survey methods,” Lawrence said. “This is a 500-foot runway extension. Going out with a terrestrial scanner or traditional topographic methods costs big bucks. We generated a point cloud and brought that into the engineering environment so they could see where it didn’t match with the design and identify each layer of material that wasn’t installed properly. With the 3-D model we gave them they were able to get some extra looks at the critical locations where the engineer had concerns.”

Orthomosaics make it possible to track changes over time, helping to ensure teams are staying on schedule, said Rick Rayhel, United States region sales manager for Microdrones. But they’re also important for quality control and safety. The ability to monitor progress makes it possible to reduce and even prevent potential errors that not only hold a project up, but that represent safety hazards for the employees working the site.

“You can fly a drone, collect images and video footage and share that with the team,” Alferieff said. “It gives you the ability to look for hazards and develop plans to remedy them.”

PRE-CONSTRUCTION AND VOLUMETRIC MEASUREMENTS

Flying a site before construction begins can help avoid headaches down the road—especially if the construction plans are off.

Heavy highway construction is a great example of where flying before work begins is beneficial, Topcon’s Henderson said. “A traditional survey could take weeks to complete, which is time most firms don’t have,” he said. “With a drone, they can fly and generate a 3-D model and validate the existing topography, which could be different from the design plans. So, they have an accurate terrain model for earthwork analysis before they get started.”

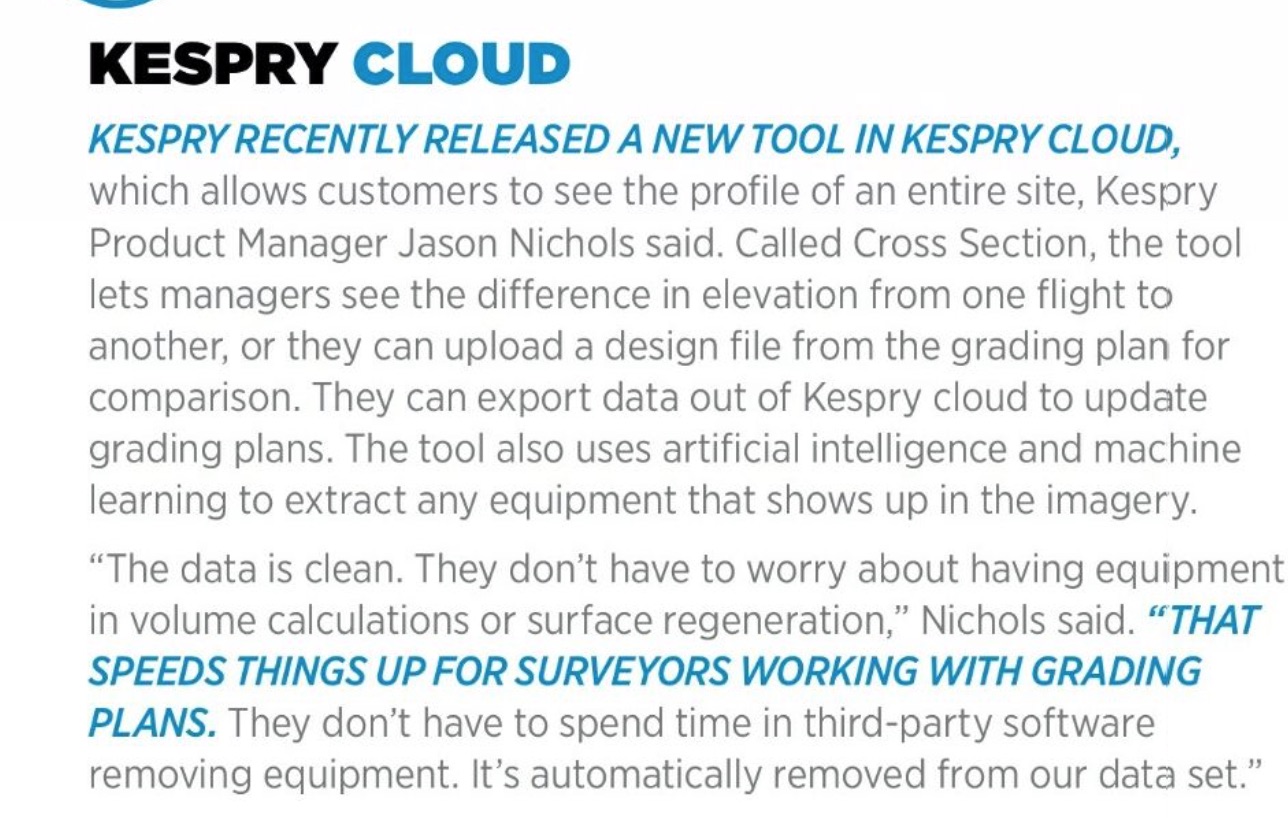

When contractors bid on a site, it’s often based on the existing plans the firm provides, Menlo Park, California-based Kespry Product Manager Jason Nichols noted. In the past, contractors would walk the site or hire a surveyor, but lack of detail for an initial bid could cost them in time and equipment. An automated solution like the Kespry drone, which uses PPK (Post-Processed Kinematics) technology, enables users to set up one known control point and fly the drone at the same time, yielding a more accurate site picture to estimate the amount of time and equipment needed to finish a project.

“A drone that has accurate GPS data and base station accuracy gets down to about two to five centimeters of accuracy,” he said. “Contractors can use that to have a stronger sense of how accurate their bid was before beginning major grading operations.”

With pre-construction flights, teams also can determine how much material needs to be moved off a site and the resources they’ll need to do it, Rayhel said. Bringing only the equipment necessary to do the job saves time and money.

Accurate volumetric measurements are also vital during projects, said Matt Rosenbalm, Microdrones sales manager for the southern U.S. Many companies get paid based on how much material is moved. They also need to ensure they have the right amount of dirt for what they’re building, and that the quantity of the dirt they’re moving meets job specs. Users can build point clouds to determine this via photogrammetry or by using LiDAR, a more expensive (yet more detailed) option.

This type of data was traditionally captured with an RTK rover, Rosenbalm added. Three or four workers would topo a site, each carrying about $25,000 worth of equipment. A 50-acre site would take all day Now, a UAS can fly the site in about 20 minutes, and only one person is needed to operate it.

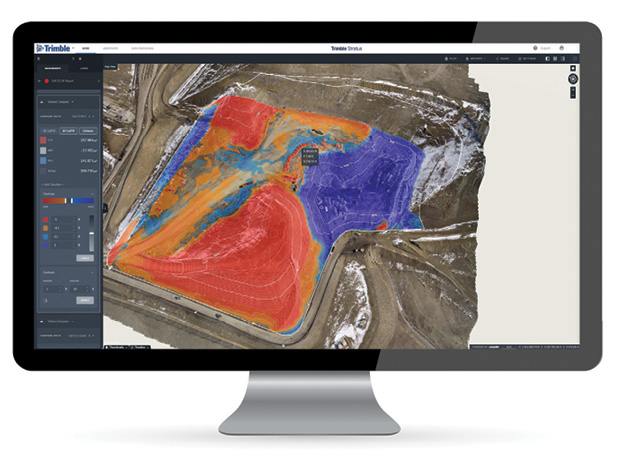

When using a drone for these kinds of measurements, it’s important to make sure the solution is on the same coordinate system as the construction project, said Jim Greenberg, UAS and landfill product manager for Trimble’s Civil Engineering and Construction Division. Trimble Stratus, a drone mapping and analytics platform, is among the products that helps with that.

When using a drone for these kinds of measurements, it’s important to make sure the solution is on the same coordinate system as the construction project, said Jim Greenberg, UAS and landfill product manager for Trimble’s Civil Engineering and Construction Division. Trimble Stratus, a drone mapping and analytics platform, is among the products that helps with that.

“Construction projects work on a local coordinate system and drones work on more of a geographic information coordinate system, which is a good system for analyzing data but not for looking at movement of material,” Greenberg said. “So people fly a drone over a project, give the company a surface, but it’s off by a few feet and not exactly relative to their design, which doesn’t allow them to make valuable measurements. The Trimble Stratus product is a portal where you take your images, some control points and upload them for processing. You get back this interactive 3-D world where you can actually go in and make measurements.”

The ability to compare current and past measurements is also useful, Greenberg added. For example, excavators on one of his client’s sites recently nicked a liner while digging a trench in a landfill. The liner is vital, as it takes water and runs it through channels before releasing it into the environment. Because the site had been flown previously, the team was able to compare the current surface to a survey taken earlier in the year, confirming that the liner was breached and making the repair straightforward.

DATA AND INTEGRATION

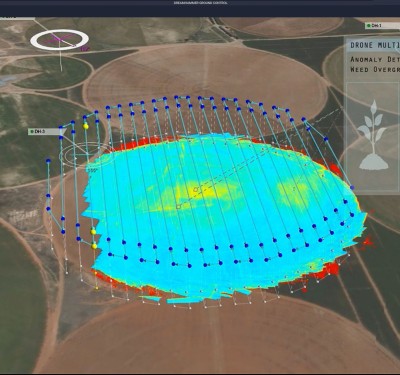

While drones can be used for a host of applications on construction sites and bring a variety of benefits, they don’t come without their challenges. One of the biggest is figuring out how to manage the massive amounts of data they supply, said Cindy Ng, head of marketing for the Intel Drone Group, based in Santa Clara, California. To extract value and help scale, there needs to be investment in visual data management and asset management software solutions.

“Organizations across industries, including construction, have a data management challenge,” Ng said. “The future is less about the specifications of the drone hardware, but more about what happens to the data, where it gets stored, how the data is transferred, how it is shared, processed, and analyzed to make the data meaningful. Drones are a means of capturing aerial data that can then be processed and analyzed, but it also needs to work in conjunction with other sources of data, such as satellite, LiDAR, and other geo-tagged data.”

When Michael Maier, engineer for Mesa, Arizona-based Empire Technology/Sitech Southwest, began learning how to use drones, he quickly discovered aerial data processing was a challenge with many different variables. There was no consistent method for sharing data, and he found the best way was to copy huge data sets onto a hard drive and physically mail it to the folks who needed to see it. Trimble Stratus, as well as other cloud solutions, represent an answer to this problem: the data collected is uploaded to the cloud, where everyone who needs the information has access to it 24/7.

“You can load a point cloud into a browser and share information,” Maier said. “I can send a link to a job manager and the engineers can open it up and see it in 3-D. They can draw measurements and do volumes. The data is consistent and the share factor is a big value.”

It’s also easy to compare volumes, look at vehicle inventory and how the job is progressing, Maier said. He described it as “like having your own private Google Earth of your job.”

Firms also need to blend the UAS data with other industry-specific software and tools—which was one of Lackey’s biggest concerns when he decided to invest in a UAS. This was actually a lot easier than he anticipated, mostly because the company already used Trimble Business Center, which integrates with the Microdrones solution they fly. The team processes the drone-collected data in the business center, which is then exported to their CAD program. SAIN also uses Trimble instruments and GPS, so it all integrates seamlessly.

At CLAYCO, the data is pulled into a range of applications that can handle 2-D images, such as orthomosaics and point clouds, Žigo said. They can use the data in typical design software applications and, to some extent, applications that produce a virtual reality environment. The RGB images aren’t as high quality as what they get from terrestrial laser scanners, so they rely on those scanners for more robust operations. All the data is put into their project management application.

At CLAYCO, the data is pulled into a range of applications that can handle 2-D images, such as orthomosaics and point clouds, Žigo said. They can use the data in typical design software applications and, to some extent, applications that produce a virtual reality environment. The RGB images aren’t as high quality as what they get from terrestrial laser scanners, so they rely on those scanners for more robust operations. All the data is put into their project management application.

THE FUTURE

While drones will never fully replace the base-and-rover systems construction companies use, more and more firms will rely on UAS for higher accuracy, quicker data turnaround and data frequency, Greenberg said.

“The same technology will be used, but it’s all going to be working together,” he added. “It won’t be just a single source of data but multiple sources of data. That has to do with AI development from both drone and software manufacturers. If you’re flying a drone on a site and have information from machine control equipment, it all gets blended together for maximum data output. That maximizes efficiency and, in turn, profitability.”

We’re already seeing what Henderson describes as a “fusion of data,” where drone data, terrestrial scanning and other RGB images are put together to tell a more complete story of the site. That’s a trend he’s seen in the last year, and something he expects to continue.

We’re already seeing what Henderson describes as a “fusion of data,” where drone data, terrestrial scanning and other RGB images are put together to tell a more complete story of the site. That’s a trend he’s seen in the last year, and something he expects to continue.

Lawrence of Woolpert predicts more automation in the future, which will be even more useful when these systems are able to fly beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS). There are already solutions available that, with a push of a button, fly a site, build a 3-D model and then create a report that tells how much dirt was moved. These types of systems will become more prevalent on construction sites, where they’ll collect data every day to ensure work is progressing as it should. Managers will automatically receive reports and can make adjustments to schedules and resources as needed.

While construction companies typically use photogrammetry and video today, leaders will invest in equipment that can grow as technology grows. They’ll fly systems that can carry multiple sensors, whether it’s LiDAR to cut through vegetation or thermal to complete building inspections. Sensors will become more accurate, and drones will become even more common.

“I’d like to see drones used more frequently and for more hardcore analysis,” Žigo said. “The hype is over now and we need to start looking at the data being collected and, based on that data, have a better understanding of other potential uses for UAS.”