The deadly uncrewed aircraft system (UAS) attack on Tower 22 in Jordan is the first time that United States ground forces have been killed in an air attack in over 70 years. Let that sink in.

It’s no wonder that the recent Air and Space Association’s Warfare Symposium experienced a shoulder-to-shoulder crowd of concerned service members and their civilian counterparts jammed in to listen to the event’s only dedicated counter-UAS panel: “Defining the Drone Threat”.

Moderated by Maj Gen R. Scott Jobe, USAF Director of Force Design, Integration and Wargaming, the all-star panelists (Michael Holl, Requirements and Capabilities Lead at RTX; Brad Reeves, Col USAF Ret. and Director of C4I Business Unit Strategy and Growth – Elbit Systems of America; and Bart Olson, VP of Future Concepts at Northrop Grumman Defense Systems) all agreed on one thing: identifying and countering current and future UAS threats continues to be “a wicked problem.” Read on for a snapshot of the key takeaways.

Modern Day IEDs

While the United States maintains one of the most formidable Air and Space Forces on the planet, UAS clearly continue to present a wide range of challenges in terms of detection, identification and response.

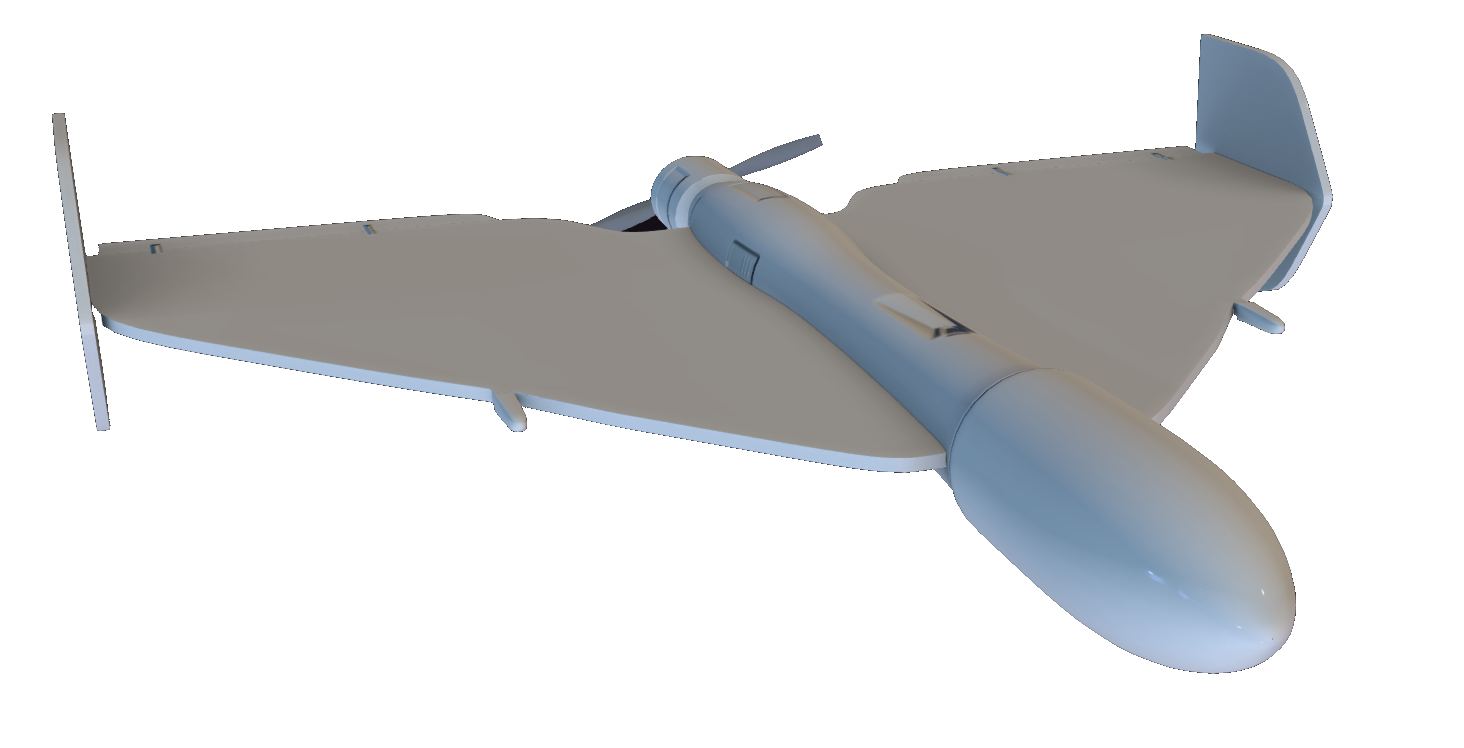

To set the stage, Elbit’s Reeves described UAS as “modern day IEDs” (improvised explosive devices). Like IEDs, UAS come at a low cost, remain widely available, easily thwart other technologies and can wreak havoc on ground forces, while remaining hard to spot and to defeat.

Today, military forces face “dark drones,” which fly autonomously without GPS and do not emit radio frequency (RF) signatures. This makes detection, friend or foe determinations and jamming close to, if not actually, impossible.

Olson from Northop agreed that “sensing” today’s UAS threat remains a hard problem, as does “making sense of what you are sensing and deciding what assets to deploy”. Timing remains a problem too. Combatants use first-person-view (FPV) and radio-controlled (RC) drones outfitted with weapons and launch them from 2km out. “This means you only have 2 minutes to do something about it,” he warned.

It won’t be just FPV drones zooming towards our troops. In Olson’s assessment, “The adversary is going to throw a whole bunch of stuff at us: cruise missiles, ballistic missiles and drones, all at the same time.” Our current command and control (C2) is not fast enough to also detect small, low-flying and fast-moving UAS, get a camera slewed to look at them, determine what it is and then put an effector on it.

But it won’t just be singular UAS zipping in with these missiles – it will be swarms of them, added Holl. He opined that China, our most sophisticated enemy, will leverage its vast resources to develop elaborate AI-powered “drone swarms.” “They will learn as they go,” he said. “As the attack happens, the drones in back will learn from the ones in front.” Military planners need to not just address current UAS threats; they need to stay ahead of future ones.

Future threats include land, surface and subsurface drones and robots, in addition to the ones in the air. There will even be uncrewed systems (UXS) that fly in the air, dive under water and pop up to crawl across the beach. China, for one, is investing heavily in ground robots, such as quadruped uncrewed ground vehicles (Q-UGVs). We’ve seen small Ukrainian uncrewed surface vehicles (USVs) take out large Russian ships. It seems we don’t just have a counter-UAS; we have a c-UXS crisis.

The enemy is, and will continue, using mass, offense, surprise, and simplicity against us in all three domains. We have to counter all of this. Yet there is no one magic solution.

There is No One-Size-Fits-All

Addressing the UAS (and UXS) threat will take a multi-layered approach using both hard and soft capabilities, riding on a significant digital backbone. It will also require holistic doctrinal changes across the entire OODA loop (observe, orient, decide and act).

The full range of technologies used in signals intelligence (SIGINT), electronic warfare (EW), for RF cyber takeover, directed energy, active and passive sensors, lasers, high powered microwaves and guns will need to be brought to bear on the UAS problem.

Above all, military forces will need to harness the power of AI and machine learning (ML), cloud and edge-computing to facilitate agile threat detection, identification and engagement, while keeping logistics tails small.

Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) will be key to coalescing these tools and forces. Part of that will be rethinking traditional service mindsets, stove-pipes and brick-and-mortar C2 sites. This may require designing a new way to efficiently execute operations, from the ground up.

Holl said, “Multiple services are all looking at the threat and all want to take the shot. We need to help the Commander to use assets most effectively”. In his opinion, that means leveraging localized disbursed forces and autonomous sensors with sufficient range for distributed execution. The Marine Corps’ Mobile All Domain Observations Sensing System (MA DOSS) is one example of this. The joint fight would also require a zero trust homegrown AIML decision aid on top of each Services’ forces, tools and ops centers.

AI can make C2 faster, allow us to get inside the enemy’s OODA loop and make sure they cannot get inside ours.

Then there’s sensors. The Tower 22 UAS threat remained undetected. Traditional radars struggle with detecting slow and low threats, not to mention several multi domain threats at the same time. UAS threats will require layered passive and active radars, including effective low-cost options, that can scan multiple frequencies (note: apparently higher frequencies help with swarms). Ideally, sensors could do more than just one thing.

For this reason, Northrop is studying acoustic, hyperspectral and optical sensors as well as fusing the existing all domain, air, sea, ground sensors that are currently spread across the services. Still, Holl said, “This is a wicked hard problem.”

Status Quo Unacceptable

While the discussion topic was framed up in terms of the UAS threat, the panel foot stomped that we need to think about this problem in terms of counter-UXS. Today’s technology is not mature enough to rely on fully for the accuracy needed to address the full range of threats. It will take industry and the military together to solve this problem. And history is a great teacher.

To address the UAS problem, Reeves suggested reflecting back on how our forces evolved in reacting to the IED threat in Afghanistan and Iraq and applying a similar framework. “We learned along the way. We started out with soft skin Humvees and ended with up-armored MRAPS (Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected vehicles).”

Similarly, we need to start thinking strategically about the UAS threat now. As one example, AI presumes we have data to learn from, collected in advance of a conflict and used to teach algorithms. We must keep the data from Ukraine and Russia and other conflicts to prime that AI pump.

We are at a watershed moment in the history of conflict. UAS have taken center stage. Conflicts across Yemen, Syria, Ukraine-Russia, Israel-Hamas and Jordan have taught us that UAS are now a lynchpin of warfare. They have also schooled us that no one is immune from the UAS threat. We face a sophisticated enemy. The status quo won’t work in the long term. To stay in front of the power curve will require both agile systems and mindsets. It seems the best play, as suggested from the AFA Warfare stage, was to learn lessons from the past, some of which were written in blood, so we are not destined to repeat them.