As the U.S. and the world move toward sustainable power solutions, windfarms have become a familiar site across parts of the U.S. and the world. Last May, President Joe Biden announced a plan to jumpstart offshore windfarm development with a commitment to growing the U.S. stable of offshore windfarms. This was probably long overdue. As of 2020, the U.K, China and Germany accounted for more than 75% of global offshore capacity, with the U.S. way down on the list.

Biden promised jobs. It’s also good news for companies operating drones in the U.S. because, for the past several years, drones have been taking over the dangerous and laborious job of inspecting turbine blades.

While drones have been in the inspection business for a while, it’s how they do their job and what that job entails that are evolving.

Usually, drone operators would collect and provide images to clients so they could pinpoint areas on blades that needed attention. Today, forward-looking drone companies are approaching the task with added tools and services in their arsenal. Key among these are: AI, which helps control flightpaths and can be used to analyze images; “start-to-finish” management packages that provide wind farm operators with sophisticated analytical reports; and databases that store information about turbines and blades by manufacturer to automate flightpaths.

AI GETS REAL

The role of AI continues to grow in the field of turbine inspection, performing functions such as autonomous drone guidance and data management applications.

Jay Choi, co-founder of Seoul, South Korea-based start-up Nearthlab, visited NASA when he was young, and dreamt of making robots and rovers for space travel. Later, while working as an engineer, he realized the dangers of infrastructure inspection. “That’s when I started to see the potential for drones,” he said via email. The Nearthlab name is a combination of “near,” “earth” and “laboratory,” representing a refocus from far-off space to inspections closer to the ground.

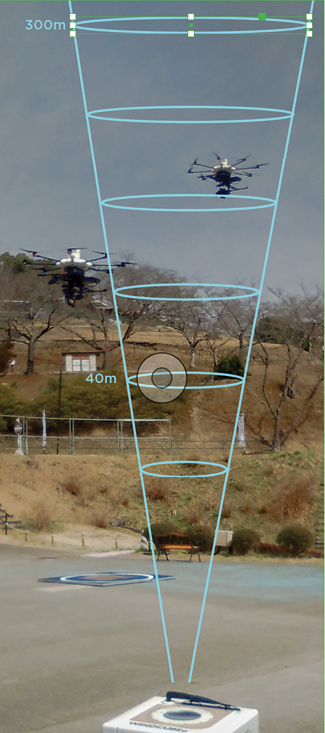

Nearthlab uses AI for its cloud-based data management platform, Zoomable, and for flightpath assistance. “Once the inspector presses the ‘start’ button, the drone takes off and maneuvers to the turbine,” Choi explained. “It recognizes the shape and position of the blades and calculates the optimal path to conduct the inspection. Using collision avoidance technology, the drone consistently flies along the blade, maintaining a close distance of about a few meters. It collects location and laser data along with high resolution photos, and uploads the information to Zoomable.”

A Nearthlab turbine inspection can be completed in about 15 minutes, versus a day with conventional methods. If there is damage to a blade, the software can pinpoint where and how big the defect is.

While the company offers two drone models, the software can be used with other UAS. The company’s Nearth Wind Basic and Nearth Wind Pro differ in size and camera power. The Basic’s base model is the DJI M210 and a 20.8 megapixel photo quality detects defects at 1 millimeter; the Pro’s base model is the DJI M600, with photo quality of 44.7 megapixels detecting defects at 0.3 millimeters.

The AI also allows Nearthlab to lessen payload size and weight, as well as shorten delivery time of reports to windfarm managers.

FULL-SERVICE DRONE OFFERINGS

Sulzer Schmid is the Swiss drone equivalent of a concierge tour operator.

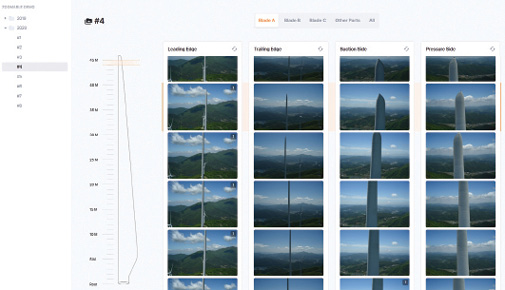

That kind of full-service approach is a hallmark of the Zurich-based company. Its “itinerary” provides end-to-end wind turbine drone inspection services, from flying the inspection drone to a fully integrated analysis of a wind farm or a turbine fleet that includes high-level business reports and analytical tools.

Along the way, Sulzer Schmid uses AI to pinpoint questionable areas on turbine blades that might need attention, saving time in determining a course of action.

“We have a comprehensive platform that makes for a unique workflow,” said Marc Hoffman, head of sales and marketing. The company’s system, dubbed 3DX™, combines AI, autonomous drones, image analysis tools and a browser-based interface. The system is collaborative and cloud-based, which allows both Sulzer Schmid and client experts to examine visual data.

Sulzer Schmid does not make its own drones. “With emphasis on the diagnostic software accompanying the drone package, we realized early on that it didn’t pay,” Hoffman noted. “But we do assemble our own payload,” he emphasized. That includes a LiDAR system, a Sony DSR RX 100m5a camera and the gimbal that carries the payload. “We also develop our own flight software.”

The data capture itself is only a very small part of the inspection system, he pointed out. “A large part is the quality of the data and the metadata, which includes annotations on the images as well as comprehensive analytics.

“The fact that we use LiDAR makes for the most precise data. We can pin down the damage to plus or minus 10-15 centimeters. The LiDAR measures the distance from root to tip of the blade. The software superimposes a number on the image so the viewer can tell which radius is being examined.” The annotations help the wind farm operator track damage over time, even after blades are repaired.

GRAPHIC BOXES SAVE TIME

Additionally, the AI identifies any anomaly on a blade and draws a graphic box around it so the blade expert can zoom in on the image. That saves considerable time for someone who has to go through 300 to 400 pictures per turbine. “Now, all the expert has to do is go from anomaly to anomaly, from box to box, to determine if a blade needs service or even if the turbine has to be stopped immediately,” Hoffman said.

Since its beginnings in 2016, Sulzer Schmid has completed more than 15,000 inspections and operates in 30-plus countries. It’s building a database of turbine-specific information, and this year has evolved its sensor package to produce higher resolution images.

“The benefit of the AI is that we’re faster than anyone in the market,” Hoffman claimed. “We guarantee five days from inspection to report. The customer receives a fully annotated inspection and only has to validate our work.”

TURBINE DATABASE, QUICK RESPONSE

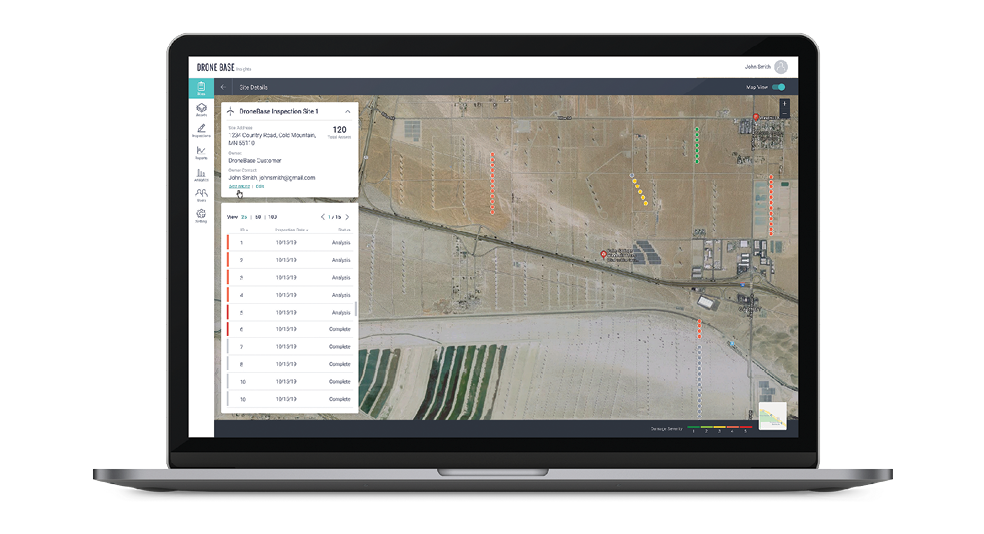

Another company leveraging AI and providing analytical tools is Santa Monica, California-located DroneBase. It’s also built a powerful database of turbine and wind farm characteristics. And, DroneBase general manager Joel LeBlanc noted, its efforts contribute to lower energy costs.

DroneBase typically does routine inspections but gets called in around catastrophic events or extreme weather condition. “Wind turbine inspections happen on schedule—and sometimes they happen if something goes wrong. Either way, it saves time and money if the inspection begins with some knowledge of the particular operation.

“DroneBase has one of the largest catalogs of turbine models in the intelligent aerial imaging industry,” LeBlanc continued. “The catalog includes all the major manufacturers and is updated on a daily basis. The database lets us create a custom flightpath for autonomous drones and contributes to the ability of our AI engine to recognize, classify and rate damages. It allows the drones to evolve their technical baselines to improve the repeatability and reliability of payloads and the data capture process.

“We’re able to help our clients identify risk, such as degraded blade integrity, which means it isn’t capturing the wind efficiently, or the need to shut down. It also lets wind farm management plan repairs such as what type of material is needed and how much labor it will take.”

The DroneBase platform delivers reports with colored icons representing individual turbines and damage severity. The customer can click on an icon or select a turbine from a list to navigate to the inspection details and analysis for that turbine. “We’ve created the category of ‘Intelligent Aerial Engineering,’” LeBlanc noted.

“Our system is compatible with most DJI-based drones as well as anything that uses a Pixhawk controller,” LeBlanc said. The company works with a network of operator partners, and typically specifies the resolution of the camera and other requirements. They’ll loan or lease equipment to operators if they need to.

“We control the flight path, the shutter speed, the distance from the blade, and can automatically fly all three blades at four passes per blade,” LeBlanc said.

DroneBase’s continued evolution is involving optimization of the autoflight guidance system and also better sensor resolution to improve the ability to inject high-resolution datasets into analytics. “We’ve doubled the number of turbines we can inspect in a day over the last two years,” LeBlanc added.

HOW HIGH IS THE WIND?

Knowing wind characteristics at different heights can be valuable information for drone users, especially if capabilities such as package deliveries becomes more common in denser areas.

That’s the thinking of Vaisala, a global leader in weather, environmental and industrial measurements headquartered in Vantaa, Finland. “As our world faces pressing societal and environmental challenges,” the company pronounces, “it’s more important than ever to base decisions on accurate, reliable data. “

“We’re involved in different markets, with weather being the common denominator,” said Tapio Haarlaa, head of aviation strategy and business development at Vaisala. “Wind is a challenge.” Haarlaa sees a need for more detailed weather information, and more precise and hyperlocal data.

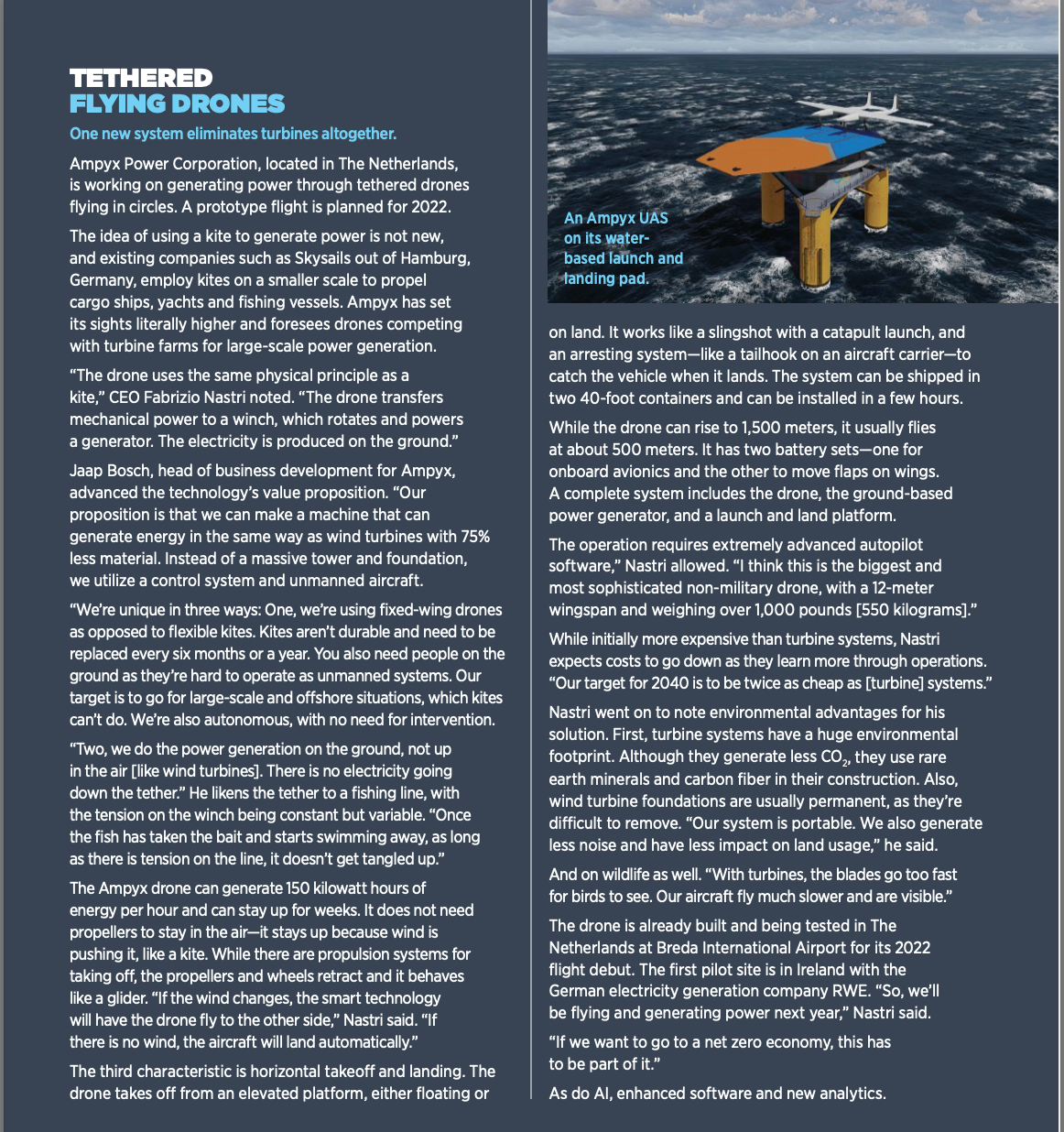

Through its Saclay, France, subsidiary, LiDAR provider Leosphere, Vaisala offers WindCube—a device that sends up a vertical LiDAR beam and is able to send back information on wind speed at different altitudes. WindCube measures the complete wind profile simultaneously at 20 different heights, keeping data availability and accuracy constant across altitudes. Designed for use in “complex terrains,” WindCube can collect data on land or offshore, and the company offers different versions of the system—for example, for those variable terrains. In a place full of mountains or many tall buildings it might take more than one WindCube to look throughout the area.

So far, Haarla’s technology is not as widely used in the drone ecosystem as it is in the energy market for building wind farma. But he expects the drone market to grow. “Before you build a wind farm, you have to make some judgments.”