Easy Aerial and Travis Air Force Base pioneer automated drone-based military perimeter security.

Located on the southwestern edge of California’s Sacramento Valley, Travis Air Force Base is both massive and historic. The giant bombers of the Strategic Air Command flew from here; now the 60th Air Mobility Wing hosts huge C-5 Galaxy and C-17 Globemaster III transports, and KC-10 Extender refuelers. The nearly 6,400-acre base is the No. 1 military air terminal in the U.S. for handling cargo and passenger traffic. More than 11,500 active and reserve personnel, nearly 4,000 civilians and 1,700-plus buildings support transport, refueling and humanitarian missions. There’s even a 200-plus bed medical center.

Keeping aircraft and airmen safe at Travis is a priority—one with an unfortunate precedent. In 2018, a minivan filled with ignited propane tanks rammed through the base’s main gate and drove into a ditch. The driver died in the resulting explosion.

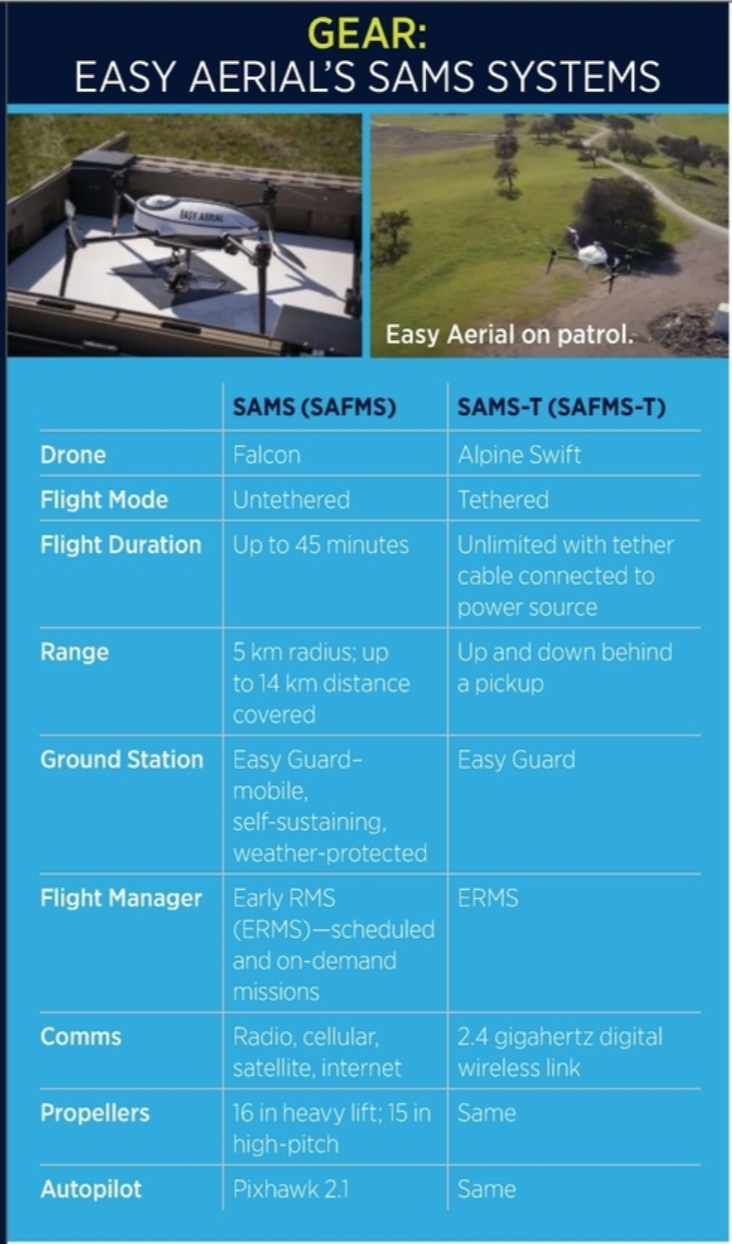

The quest for a protective edge has led to deployment of the first automated drone-based monitoring and perimeter security system for a United States Air Force installation. The free-flying Smart Aerial Monitoring System (SAMS) and the tethered SAMS-T are automated eye-in-the-sky solutions from Brooklyn-based Easy Aerial. Slightly rechristened by the Air Force as the Smart (Air Force) Monitoring System and the SAFMS-T, their rollout represents a two-year collaboration done under Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) programs, conforming to security and situational awareness requirements.

“We’re now operational,” Kenny Perkins, the civilian chief, plans and programs for the wing’s 60th Security Forces Squadron at Travis, said a few months after the system’s December deployment. “We’re working on integrating it into our daily operations. We can use it for perimeter fence security checks, should there be an incident. The next phase is to get the fire department fully up. And we’re working with the maintenance community to bring this platform to benefit them as well.”

EARLY DAYS

Easy Aerial’s path toward collaborating with the Air Force began with a literal bang.

In 2013, Ivan Stamatovski, the company’s CTO and co-founder, purchased a drone, only to crash it 5 minutes into his first flight. He had a degree in industrial design from his native Serbia, but his repair protocol involved smacking the autopilot against a table. That led to a thought: “I think I can make it better.”

His first solution was a cross-braced self-supporting frame that’s still used by Easy Aerial, a modular design where the autopilot snaps in like a Lego® block. Versions sold around the world, but Stamatovski had another, more sober, insight, perhaps fueled by the master’s in marketing he’d acquired in the U.S. “I realized I had a product, not a business.”

Stamatovski was working in a basement with two interns, who remain with the company today. Finally attracting some seed money, he found a CEO in Ido Gur, an aerospace engineer who had headed the Advanced UAV Development Group of the Israeli Air Force. They brainstormed for a direction—“power, electricity, agriculture, you name it,” Stamatovski recalled. “We settled on security. That made a lot of sense with his background.”

With Gur as a fundraising CEO, Stamatovski could concentrate on technology. “I’d come up with a drone in a box system a little before that,” he said. He developed a prototype for a web series on innovation, which he and Gur rapidly evolved.

Simple, mobile and rugged were SAMS’ hoped-for differentiators from other drone in a box vehicles. “It needs to be mobile and light, and it needs to have the least amount of parts. Our system has a single motor for the centering mechanism, with a patented cross that spins and puts the drone in place. We put it into a plastic container that was very simple, rugged and attracted a lot of attention.

HOW IT WORKS

SAMS, as Easy Aerial calls it for broad use, consists of three components:

- The Falcon quadcopter is the UAV. Its lightweight carbon fiber is durable; modular design allows payload replacement without tools. Flight time for the untethered version can reach 45 minutes, with a 5 kilometer radius.

- The Easy Guard ground station charges and protects the drone. Its battery management system is automatic and autonomous, and doesn’t need external cables. Two batteries allow for charging in 30 to 45 minutes. While battery swaps might by faster, Stamatovski noted that this method makes new operators less prone to smack into a vehicle’s other components.

Operating commands are communicated through radio, cellular, satellite or internet cable. GPS technology guides the Falcon to near the Easy Guard, where an infrared system lands it into the ground station. Then, a mechanical element rotates the drone so the vehicle’s own pads line up with the launchpad’s for charging.

An add-on Power Guard can sit in a pickup truck and provide extended electric power to the Easy Guard without the need for a fuel-based generator.

- Easy RMS handles real-time HD and monitoring detection, secure communication, smart georeferencing and multiple payload data. An AI algorithm provides autonomous activation and engagement, and various stationary perimeter security components—cameras, fence detection systems, ground sensors, virtual sensors—can automatically trigger single or multiple SAMS.

The tethered SAMS-T version—the Alpine Swift—is deployed on stationery locations or from emergency response ground vehicles. Reaching altitude vertically, it can stay in the air for more than 24 hours while transmitting HD video and telemetry through the connected electrical power line (data-over-transfer).

A GOLDEN TICKET TOWARD TRAVIS

“AFWERX was our springboard,” Stamatovski said about the Air Force’s innovation program, which offers SBIR (Small Business Innovation Research) awards for engagement with federal R&D for further growth. “They’re set up like a tech accelerator. They said, ‘OK, we’re going to break out this old boys club, where the same companies always get the deals.’”

Perkins and Stamatovski separately attended AFWERX’ 2018’s colossal “Protect the Troops” challenge. By the time the Travis team arrived for the second round, 100-150 vendors were still standing out of an initial field of 1,500. A third round in May won Easy Aerial one of 10 Golden Tickets for the winning solution. “But we were the favored solution,” Stamatovski said.

“I met with Easy Aerial; they’re very flexible and adaptable, very eager to learn and understand our processes,” Perkins recalled. “They were very eager to interface with us for the purpose for which AFWERX came to be—to bring small businesses to try and fill technology voids within the Air Force. They stood out to me, not only in their presentation, but their cordialness and fun conversations.”

It didn’t hurt that Gur could talk shop with his fellow airmen. Or that Easy Aerial’s U.S. location and parts coincided with increasing limits on Chinese components for U.S. military purposes.

BASE-IC INSTINCTS

“We were procuring for physical security and incident management,” Perkins said. “And we quickly realized that these systems were adaptable to benefit other missions. Everything we do is defense in depth, and this is another aspect of bringing that together.”

The Golden Ticket award was in May 2018, shortly after the gate crash. “There was no direct correlation between the incident at our gate and pursuit/integration of drones into our daily operations,” Perkins noted. “That said, we recognized that drones were a natural fit to enhance security and incident management on the installation.”

Armed with a mandatory signature from a commander, Stamatovski quickly set off for California with paperwork still pending for Phase One of the SBIR process. Lacking approvals to fly on the installation, a demonstration that July was held at a nearby community park that hosts an aero club and a small airstrip for model airplane enthusiasts. Commanders, Perkins, fire and emergency management representatives attended, as did Stamatovski. Eagerness paid off; SBIR Phase One was authorized that November, followed by a Phase Two implementation stage the next March.

Perkins praised another entity, the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL). “What a blessing. They helped us focus our efforts in evaluating the system. We’re required to go through the AFRL process, which is very rigorous, in the sense of writing a test plan, having clear, concise objectives.” Approval steps include appearing before a technical review board and a safety review. “These are extremely smart, very detailed guys,” Stamatovski agreed. “You have to check 50 boxes.”

Phase Two has embodied an eight-month process of deploying and integrating a drone into Travis’ air traffic, which features huge planes and long runways. “The first time we were actually flying the drone next to the runway I couldn’t believe my eyes,” Stamatovski said. “But it was the result of a very rigorous process, built into our software so that if anything happens, there’s like 10 things that mitigate any risks. It’s all automated. User error is minimized. In the end, AFRL was the ones who said, ‘We’re signing off. You guys, fly here.’”

Perkins: “We had to get the course curriculum established and approved by AFSOC, the Air Force Special Operations Command, which oversees drones for the Air Force. Then we started bringing students in for a phased certification process. The first week is in classroom, and we’re able to use one of the remote monitoring stations to run simulations, where we actually plan missions on the screen.” Easy Aerial provided training and initial certifications.

Currently, 60th Security Forces has about eight operators tasked to operating three free-flying and two tethered systems. More seasoned operators have become instructors.

DEPLOYMENT

“They promote their product as a drone in a box with the ability to respond to triggered sensors,” Perkins said about Easy Aerial. “The drone could launch, proceed to that alarm and provide video feedback into our control center. How beneficial to already have eyes on the facility and be able to communicate back to your patrolmen. They can know, when they arrive, whether there’s something to be concerned about or not.

“To date, although we have employed the system on a couple of occasions directly associated with events on/near the installation, we have not spotted any bad actors,” Perkins said. But, he reiterated, “East Aerial systems are a valuable asset to monitor activities.”

All tests to date have been with the longer-endurance tethered model. “I think it just provides you a little bit more controllability,” Perkins said. It also deals with BVLOS restrictions on the giant base. “The drone is in the back of our pickup trucks; it’s on patrol, with operators who can observe it all the time while it’s in the air.”

Software has evolved with experience. “It could be anything from a FLIR to a camera to a LiDAR even,” Stamatovski said, “and then you put communications replays, floodlights, electronic jamming. Everything’s hot-swappable.

“We prefer to let the camera do the work, so we’ve migrated to the Nighthawk camera,” Perkins said. “With that camera system, we’re able to put the drone up in altitude, declare any obstacles and then zoom in on whatever it is.” Payload choices are made in concert with Easy Aerial, based on both expertise and Air Force protocols that mandate payloads be manufacturer options. “The payload has to match the system.”

Spurred by a cross-base introduction, the Alpine Swift tethered version is now a safety multiplier working with the base’s MXG maintenance group, amid scaffolding and hangars. “This was very new to us,” Stamatovski admitted. But MXG personnel articulated the need. “They showed us, ‘Look, these guys have to strap on their harness, go into these cherry pickers, and it’s very time-consuming.’” Multiply by 72 hours a plane, 120 aircraft.

“I told them, ‘it’s a three-pronged added benefit,” Stamatovski recalled. “One, you’re not putting people in danger. Two, it’s archival; you have it recorded in a digital format that you can go and inspect and compare, [not] somebody’s subjective opinion. And you can automatically send in real time; you’re doing an inspection, you can bring in a Boeing representative on the line and ask him a question, because it’s right there.”

SHARING THE WEALTH

For Easy Aerial, Phase Three represents rolling the system out to more bases, and word about SAMS’ success at Travis has spread. “We get folks reaching out to us frequently,” Perkins reported. “I think folks gravitate toward Easy Aerial, not only because it’s a very capable system, but they know we’ve done a lot of the groundwork. Sixty percent of the work will be transferrable.”

Stamatovski: “We actually just won another SBIR with Dover Air Force Base. Dover wants to use our drones to check the lights at the end of the runway.” He envisions other applications, and agrees that the Travis precedent will ease that process. “Everything is already taken care of. It’s a list and a commander can see what the approval process is.

Easy Aerial also is pilot-testing the tethered version for U.S. Customs and Border Protection. “They throw a battery in the truck, so there’s no generators, there’s no sound,” Stamatovski said. “They stop on the border or in the desert, they lift up a drone and they have a thermal camera on it. They can see for miles around because it’s basically a 300-foot mast with a camera on it. They do eight-hour shifts when they keep the drone in the air.”

To carry larger payloads over more distance for more time, Easy Aerial is rolling out tethered and untethered hexacopters. “We took the approach of not one size fits all,” Stamatovski said. “We ask the customer what they want and work with the manufacturers to integrate it. And we’re adding AI to our fleet to be more automated.”

A half-decade in, Easy Aerial is gathering momentum. “We went through a lot together, losing funding, going back to working for free in the basement,” Stamatovski recalled. “It was worth it in the end.” Through COVID, Easy Aerial actually has doubled in size. “We started with 3-4-5 of us, and now we’ve grown to about 75 people.”

Back at Travis, Perkins hopes to pre-position a box at strategic locations on the base and mount a spotlight on the drone. He also hopes for regulatory reform re BVLOS. “I think there will be discussions with the FAA,” he said. “Government representatives other than ourselves would have to engage and work through that process. That’s the goal—let’s keep moving forward and create an environment where the rules allow us to meet the full capabilities of the system.”