Looking back on 2022, the drone industry had a banner year. Some of the big developments include positive movement on the regulatory front, commercial-off-the-shelf drones prevailed on the battlefield and some of the first-ever drone certifications. Will we see more of this in the year to come? This article provides a look back at this year’s Top 5 developments and related insights into what they might mean for the industry looking ahead.

1: The Needle Moved on Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS)

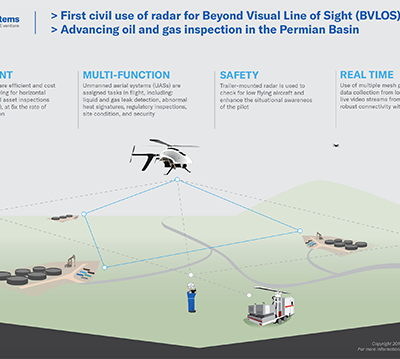

Ask anyone in the drone industry and they’ll surely say BVLOS flight remains key to operational repeatability, scalability and profitability. Since 2016, when the FAA published Part 107, these ops have occurred only when companies obtained hard fought and won waivers. While this past year witnessed an uptick in those waivers (80 of the 134 waivers, or 60% of all to date occurred in 2022), this year a cross-functional team imagined a world where BVLOS is the rule, not the exception.

After more than nine months and over thousands of hours grappling with what a world with regularized BVLOS should look like, the FAA-chartered BVLOS Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC) published its almost 400-page report in March. (See previous Inside Unmanned Systems coverage here.)

Topics ranged from flight rules, aircraft and systems, operator qualifications to third party service providers and more. Of these, the most controversial recommendation was to give drones the right of way over crewed aircraft in Low Altitude Shielded Areas (within 100 feet of a structure or critical infrastructure) and Low Altitude Non-Shielded Areas (below 400 feet, over crewed aircraft that are not equipped with an ADS-B Out). This will surely complicate what was already going to amount to a difficult and complex rulemaking process.

So far, though, the FAA has remained mum on this ARC report. Some speculate the FAA has penciled in September 2023, the month before Congress should theoretically churn out the next FAA Reauthorization Act, as a soft deadline for BVLOS rule-making. This would show good faith from the FAA in its ongoing effort to garner additional resources from the legislature.

But then there’s the not-so-great precedent of the FAA’s non-action on Section 2209 of the 2016 FAA Extension, Safety, and Security Act. This section required the FAA to create a process enabling operators and proprietors of fixed-site facilities to apply for airspace restrictions or prohibitions to prevent UAS from operating in close proximity to their facilities. In the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018, Congress further directed the FAA to implement Section 2209 through a notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) by March 31, 2019, and to issue a final rule within 12 months of publication of that NPRM. However, to date, the FAA has not issued an NPRM implementing Section 2209.

Will history repeat? Perhaps. A divided Congress, coupled with no congressionally approved FAA administrator at the helm (Billy Nolen has been the acting Administrator since April 2022) does not bode well for significant progress on a BVLOS rule in 2023.

2: Commercial Drones Changed the Face of Warfare

This year, Russia pierced the sovereignty of Ukraine. The outmanned, outgunned smaller country has staved off its aggressor in David-and-Goliath-like fashion, in part by launching an all-out small COTS drone counter-offensive.

While small drones have appeared on battlefields before, something palpably different took place here. In an unprecedented grassroots effort, outside of military channels, global commercial drone manufacturers have either worked directly with NATO, Ukrainian defense officials or nonprofits to put COTS and do-it-yourself hobby drones in the hands of military and volunteer forces. Commercial OEMs such as Draganfly, BRINC, Volatus Aerospace, Quantum Systems GmBH, and Rotor Riot (a Red Cat Holdings Inc. company), which have not historically engaged in the military sector, jumped into the fray for the first time.

These COTS drones have made a difference. Volatus Aerospace CEO Glen Lynch explained, “Our team has been in regular contact with Ukrainian defenders on the frontline. As the conflict progressed, we were told that the small drones were becoming less effective because of their low altitude and short endurance combined with Russian jamming. Ukraine needed dynamic situational awareness and accurate targeting.” He continued, “We are working with them closely to identify and supply them with the best and safest drones to use.”

Many have said the use of COTS drones has profoundly changed the way wars will be waged going forward. Christopher Miller, a retired U.S. Air Force three-star general, former deputy chief of staff for Strategic Plans and Programs and honorary president of the International Society of Military Ethics, believes the significant involvement of civilians and non-military technologies in these efforts should be further explored under the law of armed conflict (LOAC). The LOAC, a specialized subset of international humanitarian law, applies to armed hostilities and governs behavior on the battlefield. “The closer civilians and commercial technologies get to the battlefield, the more complex the issues become under the LOAC,” Miller said.

The LOAC principle of distinction, codified in the Geneva Conventions, requires that parties to an armed conflict must “at all times distinguish between the civilian population and combatants and between civilian objects and military objectives and accordingly shall direct their operations only. …” The mere presence of non-flagged commercial drones, in and of itself, challenges this important military concept.

“How can a military force distinguish between an innocent hobby drone being flown for recreation and one being used to target its forces? The laws of armed conflict and individual countries’ legal frameworks for regulating these technologies are under pressure to adapt,” Miller said.

Theoretical military concepts aside, the success of commercial drones in battle highlights a significant physical challenge for which military and homeland security officials should plan now. According to retired U.S. Air Force Maj. Gen. James Poss, commercial drones have proven so effective they have essentially created a new way of warfare. “If a patchwork group of NGOS and commercial companies can have such an impact on the battlefield, imagine the impact terrorists could have in our homeland,” he said.

This war has not only created an unparalleled demand for COTS drones by military forces, it also reinforced the need for remote identification, counter-drone technology and enhanced counter-drone authorities in the U.S. We anticipate seeing the need for much more of all of this tech, across the board, in the future — and that “drone wars” will continue into 2023 and well beyond.

3: The Remote ID Rule Really Rolled Out

In July, over a year after RaceDayQuads (RDQ) initiated a legal challenge to the legality of the remote identification (RID) rule, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit ruled in favor of the FAA. The RID, which creates (as the FAA refers to it) a requirement for drones to have a “digital license plate,” took over four years from time of the original 2017 RID ARC, through the 2020 NPRM (which garnered over 53,000 public comments) and to the January 2021 rule publication in the Federal Register.

RDQ challenged the RID rule on its face, with allegations from constitutional privacy violations to administrative process fouls. This challenge hung up drone operations, manufacturing and progress on potential standards for more than a year. Why? Because the FAA made RID one of the prerequisites for higher risk operations in its Operations Over People (OOP) rule (published on the same day as RID) and a cornerstone of a UAS traffic management (UTM) system. The RID rule required drone manufacturer compliance by September 2022, but most OEMs remained unwilling to roll the dice on requirements that remained on shaky legal ground.

In the end, the court found the FAA had procedurally played by the rules and the RID rule was good to go, on its face. (See previous Inside Unmanned Systems coverage here.)

In August, the FAA published its first RID-acceptable Means of Compliance. One month later, just in the nick of time, the FAA essentially (but not technically) pushed back its OEM compliance date to December 16, when it issued a Notification of Enforcement Policy stating it would ”consider all circumstances, in particular, the delay in the FAA’s acceptance of a means of compliance, when exercising its discretion whether to take enforcement action.”

That said, in early September, OEMs started filing and the FAA started approving Declarations of Compliance (DOCs). With minimal fanfare, Microdrones, Wingtra and DJI were the first out of the gate to have their RID DOC accepted.

Drone operators still do not have to fly these RID-compliant drones until September 2023, but can do so before that (and probably already are). Little to no information, however, has been publicized about the technology needed to read RID broadcasts. Expect to see RID in full effect later next year. Secondary impacts will include full operationalization of all categories of OOP and maybe even additional inching forward of UTM.

4: Counter-Drone Tech & Authorities Got Serious Attention

At the same time that COTS drones filled the skies over the Russia-Ukraine conflict, at home drone threats ramped up this year. From cross-border incursions, prison contraband drops to hundreds of reports of drones in places where they should not have been (airports, over professional sports stadiums etc.), clueless, careless and criminal drone users abounded. (See previous Inside Unmanned Systems coverage here.)

This grabbed the attention at the highest levels of government. In April, the White House published the nation’s first Domestic Counter Unmanned Aircraft Systems National Action Plan. Key government officials testified before Congress, several times over. In a June Senate hearing focused on the evolving threat that drones pose to the U.S., Brad Wiegmann, Justice Department deputy assistant attorney general in the National Security Division, warned it’s “only a matter of time” before a drone attacks a mass gathering in the country. Congress generated several counter-drone bills to not only continue expiring Department of Homeland Security and Justice Department detection and mitigation authorities, but to also expand these authorities in a limited manner to state, local, tribal and territorial law enforcement agents.

As the clock ticked on DHS and DOJ expiring authorities (which sunsetted in September), instead of passing a law to validate and expand them, Congress temporarily extended them—not once, but twice.

Counter-drone law, while important, appears to be too difficult to do at this time. Albeit a bipartisan issue, a divided Congress does not help in moving this forward. It appears some lawmakers continue to have a fundamental lack of understanding of the precision and safety of the various technologies and an uninformed fear of potential privacy and civil liberties encroachments.

Our prediction: Congress will kick the can on counter-drone authorities for DHS and DOJ until next year’s FAA Reauthorization Act. These authorities will continue to hang in the balance, with continued temporary extensions.

5: The FAA Type & Product Certified its First Drone

Until this fall, if anyone asked, “How many drones has the FAA type certified?” (aka, aircraft design approved) the answer would have been, “None.” That changed in September when the FAA issued the first-of-its-kind non-military unmanned aircraft type certification to Matternet for its M2 delivery drone. Only type-certified aircraft qualify for Part 135 air carrier operating licenses; otherwise, companies must receive an exemption. This process took the company four years from start to finish.

Three months later, the FAA also granted Matternet’s Production Certificate. This gives the official stamp of approval to the company’s capability to manufacture aircraft that conform to its type design and allows it to manufacture, test and issue airworthiness certificates for its M2 drones.

These ground-breaking approvals may have paved the way for all of those waiting in the wings for their type Certification approvals, including Airobotics, Flytrex, Percepto Robotics, Wingcopter GmBH, Amazon and Zipline, to name a few. 2023 may be the year where type and production certificates really start taking off.

And So Much More!

We limited this list to this year’s Top 5 drone developments, but so much more happened in the industry. Funds continued to flow into drone-related tech. In-person events and networking kicked back up fully, after almost two years of COVID setbacks. New collaborations abounded. Recreational flyers received some clarity from the FAA on the process to determine where non-RID compliant drones can fly. And words mattered, as the FAA and non-profits continued to pivot to terminology to be more inclusive.

If looking back on this year is an indicator of things to come, the drone industry has a lot to look forward to in 2023. Happy New Year!