Energized by lessons from the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, countries around the world are expected to continue adding unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) to their military arsenals, driving up annual global spending for defense drones by 36 percent over the coming decade.

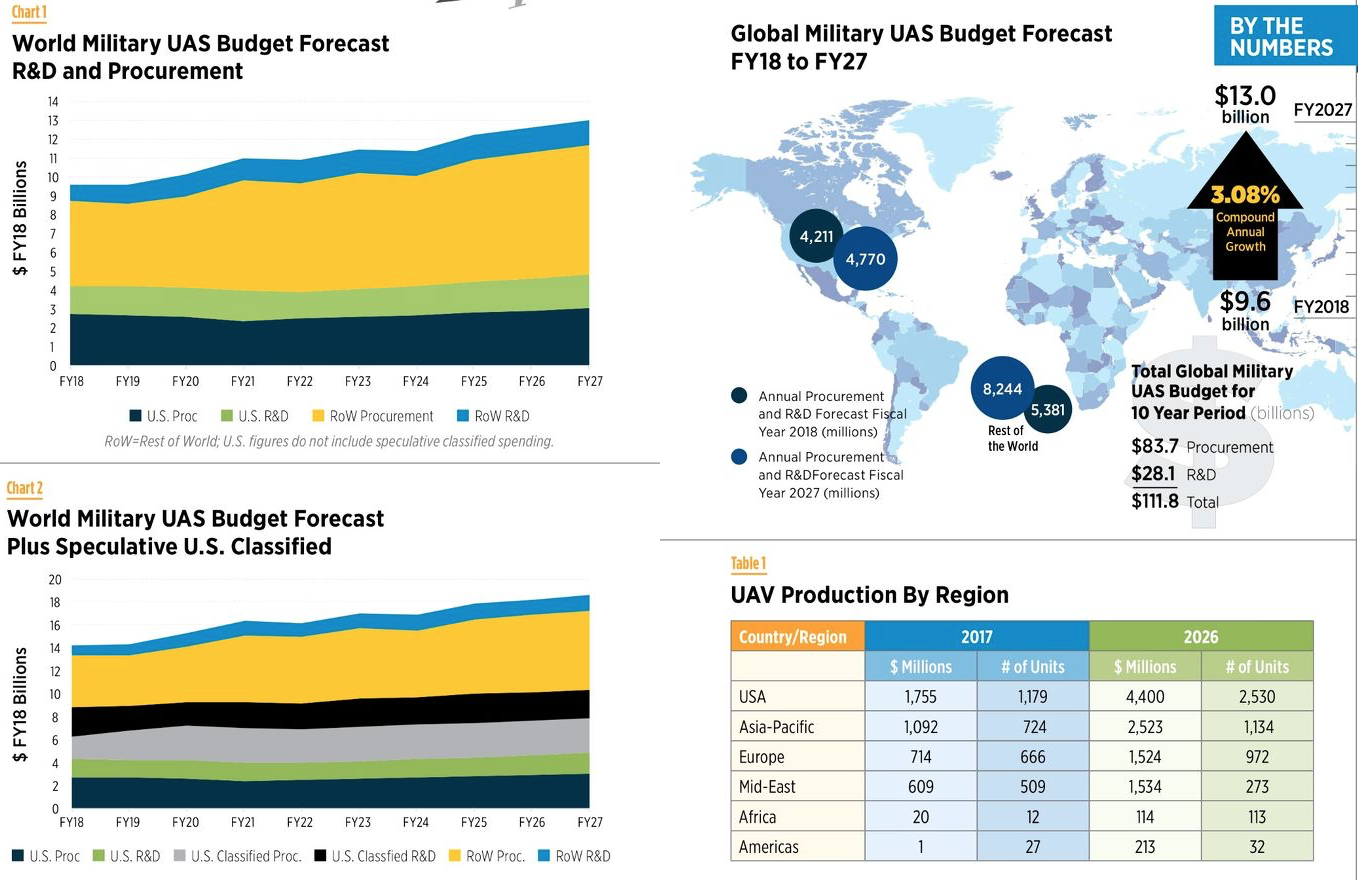

That growth in spending reflects a jump from $9.6 billion in unclassified procurement and RDT&E (research, development, test and evaluation) from fiscal year 2018 (FY18) to about $13 billion in FY27 inclusive, according to the Teal Group, which recently released its market study World Military Unmanned Aerial Systems: Market Profile and Forecast. From FY18 through FY27 military officials are expected to spend a total of $28.1 billion on RTD&E and $83.7 billion on procurement.

“I see it as a growth industry—absolutely—because people have had the opportunity to observe us now, and so now you see other nations and you see non-nation states taking advantage of this technology,” said retired Army Lt. Gen. Ron Burgess, who is now senior counsel for national security programs, cyber programs and military affairs at Auburn University.

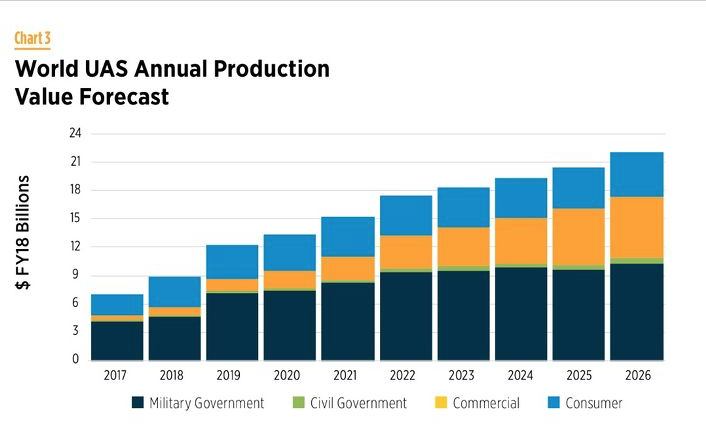

That steady expansion means the value of the market for military UAVs will continue to be larger than that of the individual markets for civil, consumer or commercial missions—at least for the next 10 years.

No Micro UAVs

The numbers are as interesting for what they do not include as for what they do. Teal did not try to estimate the impact of new regional conflicts, though the study authors said, “such events are quite likely.” Also not considered are more “drastic” events such as an escalation in the dispute over the islands in the East China Sea.

One thing that has been left out for the sake of clarity are the micro UAVs—the really small quadcoptors and other unmanned aircraft valued at less than $10,000.

Including micro UAVs “can distort the picture of what’s really happening,” study co-author Steven Zaloga said. “So one year the forecast for the United States will be, say, six thousand UAVs—of which maybe 50 are the large substantial UAV’s and the remaining 5,550 are these little small things. Then the next year it will drop to 50 because they’re not buying the small stuff.” It makes it look like the market disappeared, he said.

Zaloga pointed out there’s no real program of record in the U.S. for a militarized quadcopter and he doesn’t think that will change in the immediate future. The U.S. Army isn’t under pressure to buy large quantities of small UAVs as long as there’s not a lot of infantry style fighting going on, he said. The services also want something that is more secure and, most importantly, has a battery that enables longer endurance flights—something, Zaloga believes, they are expecting the private sector to produce without prodding.

“The Army vaguely talks about having a requirement for (small UAVs),” Zaloga said, “but when you go and look in the budget, where are they funding this? Are they putting any real money there? The answer is no.”

U.S. Keeps Its Lead

Though the military UAV sector is expected to become increasingly international the United States will continue to dominate, Teal predicted. The United States will account for 57 percent of the unclassified research and development (R&D) spending on UAV technology over the next decade and about 32 percent of the procurement. Add in Teal’s estimates of classified U.S. spending and that jumps to 76 percent of R&D and 49 percent of procurement.

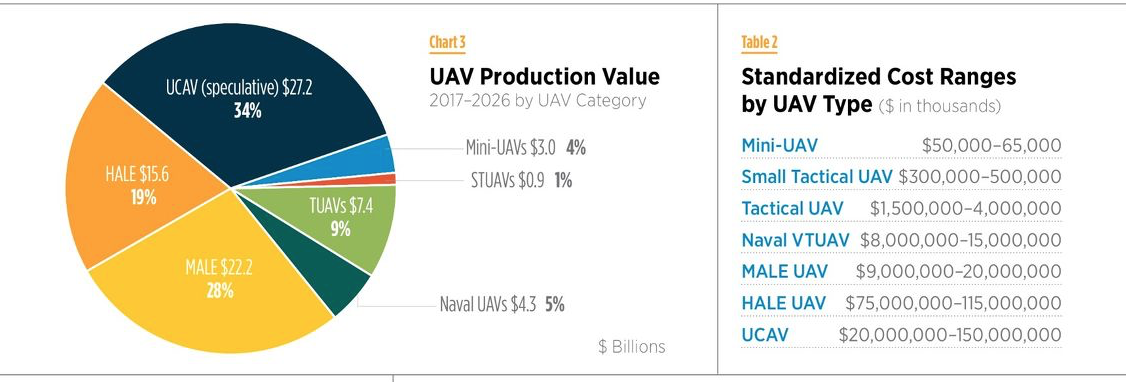

A comparison of production value of the unmanned aircraft (that is the value of the UAVs themselves not including things like sensors, modifications, ground control systems and other procurement costs) shows the U.S. growing from an estimated production of 1,179 UAVs worth $1.8 billion in 2017 to 2,530 drones in 2026 worth $4.4 billion. The Asia-Pacific is the next most active market by region as measured by both the number of air vehicles produced and by the value of those air vehicles, according to Teal, followed by Europe, the Middle East, Africa and the Americas (see Table 1 for the numbers). The study estimated that UAV production would increase from current worldwide UAV production of $4.2 billion annually in 2017 to $10.3 billion in 2026—that is $80.5 billion in total spending on just the unmanned aircraft over the next 10 years (Note: this is slightly different from the FY18 to FY27 time frame mentioned earlier. The value of each unit is standardized using cost ranges to enable practical forecasts. Those ranges reflect a portion of system costs. See Table 2).

Though micro UAVs didn’t make the cut, there is real activity in the next level up—the mini UAVs, which Teal categorizes as costing $50,000-$65,000. There were some 2,530 of these produced in the U.S. in 2017 with a value of about $189 million. That is expected to rise to 4,439 units with a value of $363 million by 2026.

Teal forecast that the biggest slice of the UAV market, at $27.2 billion, would be centered on the development of new Uninhabited Combat Air Vehicles or UCAVs—unmanned aircraft that could perform at least some of the roles of combat aircraft. Zaloga believes the Air Force already has a classified version of such a program in the works as a replacement for the now-retired F-117 Nighthawk stealth attack plane—a UAV that could slip past sensors to take out air defenses without risking a pilot.

“My belief is that the Air Force is either flying that right now or on the verge of flying it—or certainly has a requirement,” Zaloga said.

Those working on UCAVs as true combat aircraft, however, have some real challenges ahead, he said. “I think that one is a lot further down the road because it’s much more difficult to replace the human as the main sensor on the aircraft,” Zaloga said. “The human is much more versatile than most electro-optical or mixed electro-optical/radar sensors that we have right now.”

Zaloga expects the second largest segment of the market to be the Medium Altitude/Long Endurance (MALE) UAVs like the Predator and Heron. With an endurance of about 24 hours and long-range capability these are generally used for operational reconnaissance. Teal forecast a total production value over 10 years at $22.2 billion (see Chart 4).

Export Fight Brewing

All of those numbers could shift, at least for U.S. manufacturers, if the Trump administration follows through on reported plans to ease export restrictions.

“The State Department especially has been very obstructive in the sale of larger UAVs, ones that are capable of being armed, into the export market—I mean to the extent that it’s actually gotten ridiculous,” Zaloga said. “If you look at, for example, the long time it took the U.S. government to allow Italy to arm the Predators that they bought. They were one of the earliest European adoptees of Predators but they were the original unarmed predators. So then the Italian government came and said: ‘Well, we’d like to arm them with Hellfires (Hellfire missiles) just like the U.S. ones are.’ It took years and years and years.”

“A change in U.S. policy on the export of large (i.e. MTCR Category I) UAS will greatly enhance America’s ability to provide much needed UAS technology to its closest partners and allies,” said Remy Nathan, vice president for international affairs at the Aerospace Industries Association, in a written statement. “Current restrictions on exports have allowed foreign competitors, like the Chinese, to provide their UAS technology to some of our most strategic partners and allies. This hurts U.S. industry and jobs and degrades our technological edge, while funding Chinese R&D to further refine their systems and ability to support global operations—an advantage the U.S. currently maintains.”

The restrictions have left the market open to competitors, Zaloga agreed. Though the Israelis are currently the largest exporters, he said, the Chinese have recognized and are working on seizing the opportunity—a development with potentially wide ramifications.

“China now has ambitions to compete in the big market—to directly compete against the United States and the Europeans and the Russians with high tech products,” Zaloga said. “So they’re trying to do that in the aircraft field but they’ve got to get a foot in the door. They’ve got to convince customers that their products are equivalent in quality to the other big players’. And so you can see that they’re putting a lot of effort in this field of endurance UAVs that can be armed and they are doing it because the U.S. manufacturers basically have an arm tied behind their back because of the State Department restrictions.”

What’s very striking, Zaloga said, is the Chinese aren’t necessarily pushing in all UAV sectors.

“Where they’re pushing very heavily is armed UAVs, roughly in the category from Predator up through Reaper, and the reason is that has been their big foot in the door in the aerospace market. They’ve been starting to be able to sell those things in places where they can’t sell conventional military aircraft or anything else. The Saudis are buying them. The UAE is buying. They’ve been sold to a number of African countries. So China’s looking, saying, ‘OK the United States has restrictions on the sale of some of their aerospace systems…this would be a good foot in the door for us.’”

Nathan pointed out that foot in the door can go well beyond a one-time sale. The lifecycle of some of unmanned systems exceeds 20-30 years, fostering a long-term relationship centered around logistics and sustainment.

There’s even talk about a deal to co-produce Chinese armed UAVs in Saudi Arabia, Zaloga said, “and in significant numbers. I mean in the hundreds, which in that category is a big number.”

The systems the Chinese are offering are no longer copies of systems available elsewhere, Zaloga said. “At one time a lot of their stuff was just kind of copies, almost direct copies of U.S. programs. You could see a Chinese UAV and say ‘Aha, that’s the equivalent of the Q7’ or ‘that’s the equivalent of some Israeli program and that’s the equivalent of a Predator.’ Now they have multiple programs, from multiple firms, competing in practically all of the niches.”

The changes in the Chinese program are not widely known, Zaloga suggested, because the new equipment is not necessarily shown at the more popular air shows. “I went over to Zhuhai over to the big Chinese air show in 2016 (Airshow China), and I was shocked at the rapid development of UAS in China. The number of systems out there is astonishing—and the growing sophistication of the systems.”

Once people are convinced the Chinese products are worth buying, it will give them entrée into other opportunities,” Zaloga said. “The Chinese rightly think this gives them an opportunity to break into markets that otherwise they would never had any chance to break into.