A move is afoot in Congress, at the White House, the FAA and other agencies to allow more federal agencies, as well as state, tribal and local governments, to use counter-UAS systems to protect their facilities, including airports, from rogue drones.

So far, Congress has only authorized the departments of Defense, Energy, Justice and Homeland Security to engage in limited UAS detection and mitigation efforts to counter potentially threatening UAS, and the FAA has been authorized to conduct some limited tests of counter-UAS systems.

That leaves other federal agencies; state, local, tribal and territorial (SLTT) governments; as well as the owners of critical infrastructure such as stadiums, airports, outdoor entertainment venues and other facilities unable to use counter-UAS systems on their own, although police can still pursue rogue drone operators on the ground.

Action is taking place on several fronts. There is a pending Senate bill, S. 1631, and a companion House bill, H.R. 4333, which have some minor differences.

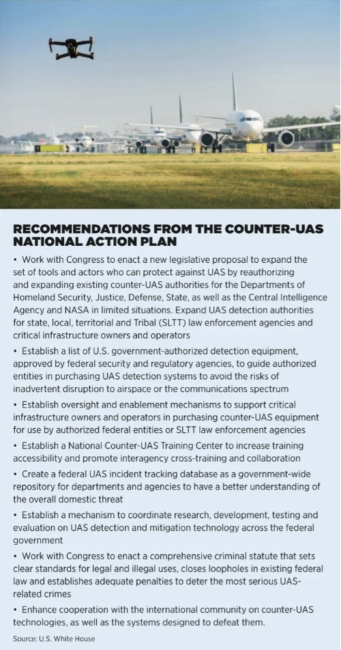

The White House has the Counter Unmanned Aircraft Systems National Action Plan which, among other things, calls for the executive branch to work with Congress on a proposal to expand counter-UAS responsibility and create a pilot program to expand UAS detection authority for SLTT law enforcement and the owners of critical infrastructure. The congressional bills are partly based on this plan, although the plan also has elements the White House could pursue on its own.

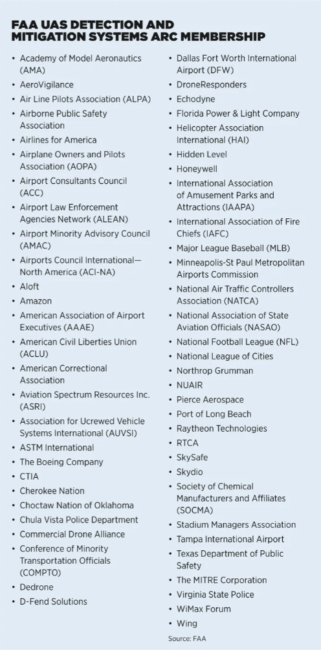

While this is going on, the FAA has chartered a counter FAA UAS Detection and Mitigation Systems Aviation Rulemaking Committee, or ARC, with a wide spectrum of membership (see membership list).

LEGISLATIVE HURDLES

Sen. Gary Peters (D-Michigan), chairman of the Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, reintroduced last year’s “Safeguarding the Homeland from the Threats Posed by Unmanned Aircraft Systems Act,” which would take significant steps to expand counter-UAS systems.

Following the lead of the national action plan, the bill would reauthorize the DHS and DOJ’s current permission to counter UAS threats and also authorize the Transportation Security Administration to proactively protect transportation infrastructure from drone threats, thereby roping in airports and other transportation sites for protection.

It also would allow SLTT and the owners of critical infrastructure to use drone detection technology that has been approved by the DHS. It creates a pilot program that would require coordination between state, local and federal law enforcement to mitigate UAS threats, and, finally, requires DHS to develop a database of security-related UAS incidents that occur inside the United States.

“Attacks or accidents caused by unmanned aircraft systems could have catastrophic effects on our national and economic security,” Peters said upon introducing the bill. “Federal agencies must have the tools they need to address this evolving security threat. This bipartisan bill will help our federal government protect high-profile events and critical infrastructure from recklessly or nefariously operated drones, and ensure that we are respecting the rights and liberties of responsible drone users.”

Peters noted that according to FAA estimates, by next year 2.3 million drones will be registered to fly in U.S. airspace, creating a higher risk of accidents and misuse by foreign adversaries or criminal organizations.

The bill, and its House counterpart, have yet to go through committees for markup, and are subject to review by three committees each. According to the website Govtrack, which monitors legislation, Peters’ bill has a 27% chance of being enacted.

Either way, the legislation is not likely to pass as a stand-alone bill, but be part of a larger package, especially when Congress is at loggerheads on legislation that is usually conflict-free, such as defense spending bills.

And, there are lawmakers who don’t like the idea of expanding counter-UAS authority. Opposition to it, in fact, comes from both sides of the aisle. Some lawmakers have privacy concerns about expanding drone detection systems, while others fear giving the FBI an expanded role at a time when the agency is under scrutiny.

REAUTHORIZATIONS

Meanwhile, the DHS is recommending expansion of drone detection authority, to include some owners of critical infrastructure, as part of its reauthorization.

Brent Cotton, director of the C-UAS Program Management Office at the Department of Homeland Security, said the agency wants some owners and operators of critical infrastructure to have “detect, track and identify authority.

“Not counter-UAS authority, right?” he said during a panel discussion at the FAA UAS Symposium earlier this year. “We’re going in baby steps here and you don’t want counter-UAS authority, but you would like to have probably the ability to know what’s going on in your airspace and around your facility, right?”

A Washington source agreed that mitigation capability is a no-go for most agencies.

“Mitigation is very, very hard. And there are very few instances in the continental United States where mitigation has ever been employed in terms of like a technology deployment using RF [radio frequency] jamming or a spoofing or a cyber takeover or a net or any kind of that sort of kinetic or non-kinetic interference,” the source said. “The way you can still engage in what we’ll call mitigation for these purposes—but it’s not any of those things—is through detect, tracking, identifying. You can send someone out to the operator and say, ‘land this drone.’”

Cotton said the recommendations to partner with state, local and tribal officials could get additional counter-UAS protection at critical facilities, but “keep in mind, this is all very controversial. This is in no way a slam dunk…we are really battling the privacy, civil rights and civil liberties concerns on the Hill. And that’s important, and we need to make sure that those things are covered appropriately. But we’re balancing that with the need for us to be able to push out the security boundary, or I should say, the need for critical infrastructure owners or operators to push out their security boundary. So, they can have awareness of those drones long before they become a problem, could potentially commence an attack or do surveillance or even just cause a safety hazard.”

The expansion effort has been going on since last year—the White House action plan and Peters’ Senate bill were both originally introduced in 2022—and could easily slide into next year.

“The way the legislative process is moving this year is very slow,” Cotton said. “It’s a very busy time. It’s possible we will see another clean reauthorization followed by continued negotiations over expansion.”

Eventually, if the various efforts to expand authority come through, there would be an application process for SLTT officials, or the owners of critical infrastructure, to determine if a counter-UAS system would be warranted. Those seeking the authorization would need to show there is a legitimate threat and that they have the funding to support the counter-UAS technology and operation.

COUNTER-UAS ARC

This is the background for the work being done by the ARC, which began in May. A final report is expected to be issued to the FAA in 2024.

Michael Robbins, the chief advocacy officer for AUVSI, said at the FAA UAS Symposium the ARC has finished the “easy part” of its work, putting ideas on the table. In phase II, it’s going to be “pressure testing” against specific types of use cases, including counter-contraband delivery testing at a prison.

“We’ve actually identified a very specific prison,” he said. “We’re going to test some theory at that prison and see how it works, [and at] some other facilities as well.”

The ARC has 58 members, which the FAA said represent a diverse set of aviation stakeholders, including those from the UAS industry.

“What will work in one facility may not, and likely won’t, work at another facility, at least in a perfect way,” Robbins said. “So, what the ARC is attempting to do is not prescribe necessarily in great detail how best to go about integrating UAS detection—or some cases, mitigation technologies—into those facilities.” Instead, it will set out “a broader framework, or playbook, if you will, of how the FAA from its safety role integrates those safely without being overly prescriptive, and also ensuring cooperation with security partners [that] have a role in this as well.”

As part of its reauthorization act of 2018, the FAA also was required to test and evaluate systems that detect or mitigate UAS risks at five airports: Atlantic City International Airport, home of the FAA’s William J. Hughes Technical Center, followed by Syracuse Hancock International Airport in New York; Rickenbacker International Airport in Columbus, Ohio; Huntsville International Airport in Alabama; and Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. That testing is well under way, according to the FAA, with more than 10,500 flights so far.

Robbins said there is a special working group within the ARC dedicated to airports. “I think there’s a recognition…that airports are very much an important part of the security community and have unique security needs that are different than fixed sites,” he said. “…I anticipate coming out of the ARC and legislative process and the broader regulatory process, the airports are very much a part of whatever occurs going forward. Airports will be front and center on that.”