Vladimir Putin’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine and Russia’s initial defeats in the face of heroic resistance have destabilized many assumptions on how the international system and military power work.

In a terrible conflict driven by clashes of tanks, artillery and infantry, the role of unmanned systems may seem marginal. But that would be mistaken: Ukraine has demonstrated how low-cost unmanned capabilities can be leveraged effectively in a high-intensity conflict, with outsized impact on perceptions of the war at home and abroad.

Other armed forces will observe these lessons and attempt to adopt unmanned capabilities based on their performance in Ukraine. Furthermore, the war has shown how private and civilian commercial actors are more capable than ever to directly furnish belligerents with militarily effective unmanned systems outside ordinary state-to-state channels.

THE ISR REVOLUTION

“The drones used in this war provide key ISR capability to all belligerents, along with guiding forces and munitions to targets,” Samuel Bendett, an AI adviser for the Center of Naval Analysis’s Russian Studies program and a CNAS (Center for a New American Security) adjunct, wrote to Inside Unmanned Systems. Drone surveillance particularly is being wielded to achieve stunningly precise artillery fires on convoys, encampments and individual vehicles even without using precisions guided shells.

Both Ukraine and Russia manufacture a range of indigenous ISR UAVs. Ukraine operates about 300 each of the smaller A1-SM Furia flying wing, and hand-launched Leleka-100 and Spectator tactical UAVs from DEVIRO and OJSC Meridean for artillery spotting, as well as larger “People’s Drone” PD-1s (UKRSPECSYSTEMS) and UKRJET UJ-22s. Russian mainstays include the shorter-range, folding, catapult-launched Orlan-10 (from the Special Technology Center in Saint Petersburg) and Eleron-3 (JSC Enics), supplemented by longer-endurance Forpost drones formerly produced under license.

Because drone spotters are not confined to the line of contact as a ground-based forward observer is, they can acquire targets behind enemy lines, including vehicle columns that haven’t yet dispersed into combat formations, as well as vulnerable logistical and fire support assets.

On the tactical side, even an individual mortar team can employ a microdrone with adequate range to locate enemy forces concealed out of line of sight and adjust fire to precisely target their position.

UAVs’ ability to record both artillery fire and their own missile strikes with chilling intimacy has also yielded highly effective propaganda. “Each side seeks to amplify its own use of drones, either via massive social media postings or via carefully edited official PR videos…we have to remember that we are not getting a full picture if we just analyzed Twitter, Telegram and TikTok,” Bendett cautioned.

Drone surveillance has also provided never-before-seen high-quality imagery of ground engagements that evoke the isometric perspective of strategy videogames: roadside ambushes by anti-tank weapons, soldiers tossing grenades at enemies on the other side of walls and tanks shooting through holes in ruined houses to strike enemy convoys. Many of these ambushes were likely facilitated by orbiting eyes in the sky.

Both sides are apparently using jamming and other counter-UAS methods, Bendett noted, with Russia’s defense ministry claiming destruction of hundreds of drones and Ukraine releasing imagery of seemingly undamaged UAVs it has captured.

BAYRAKTAR, YET AGAIN

The occupier came to us, to Ukraine

With their brand new uniforms

and war machines

But their inventory melted a bit

Bayraktar!

—Bayraktar Song, by Taras Borovok

Ukraine conducted its first UCAV strike on October 26, 2021, using a Turkish-built TB2 Bayraktar to destroy a separatist-operated howitzer. In 2020, the MALE (medium-altitude long-endurance) Bayraktars, armed with laser-guided MAM-C and MAM-L missiles, had garnered much attention for devastating mechanized forces and air defenses in Libya, Syria and the Nagorno-Karabakh, to seemingly decisive effect. Bayraktar losses in Libya and Syria were substantial but tolerable, and negligible in Nagorno-Karabakh.

Ukraine ordered 48 Bayraktars in 2019, with 18 to 24 active by the commencement of the current hostilities. Turkey delivered at least 16 more afterward without the hand-wringing that has occurred over proposed NATO transfers of manned warplanes.

Many military analysts expected Ukraine’s Bayraktars would prove less successful due to Russia’s ability to destroy drones on the ground with air/missile strikes, or shoot them down with fighters, and also because of its denser, higher-quality integrated air defense systems (IADS).

But curiously, Russian planners overlooked the TB2s in the war-opening barrage of missile and air strikes, giving their operators time to disperse before commencing offensive strikes three to four days into the war.

Bayraktar camera recordings show the destruction of multiple Buk and Tor air defense systems, which in theory had adequate range to engage the drones at maximum altitude. Other targets include supply trucks, towed artillery, command vehicles/posts and even fuel trains in Russian-occupied Crimea, destruction of which may have slowed Russia’s southern offensive.

At sea, Bayraktars inflicted staggering damage to Russian forces around Snake Island, in the Black Sea. A flurry of recordings from April 26 to May 8 show TB2s destroying four Raptor-class patrol boats, a Sarna-class landing craft, multiple air defense systems (Tor, Strela and ZU-23) and even a hovering Mi-8 helicopter roping troops down onto the tiny island.

TB2s also helped spot long-distance artillery strikes that destroyed at least nine Russian combat helicopters at Kherson International Airport, prompting withdrawal of the remainder.

Bayraktar imagery galvanized Ukrainian morale, leading to popularization of the “Bayraktar Song” extolling its effectiveness against Russian invaders. Moscow, meanwhile, claimed to have destroyed more Bayraktars than Ukraine ever owned, and even faked images of TB2 kills.

Bayraktar footage declined over time, perhaps reflecting attrition from improved Russian air defense deployments, depletion of missile stocks or stricter operational security.

However, the crash of a Bayraktar on Russian soil suggests the apparently hard-to-detect drones may have performed penetrating bombing raids on a Russian fuel depot in Bryansk, 65 miles northeast of the border.

By late May, images confirmed loss of only eight Bayraktars. Analysts remain confounded by the failure of Russian IADS to contain Bayraktar attacks. Some early fiascos were attributable to incompetence: i.e., failure to turn air defense systems on. Though not a stealth aircraft, the Bayraktar’s small radar cross section also may pose challenges. British military analyst Justin Bronk also speculated Russian forces couldn’t employ counter-drone electronic warfare extensively without disrupting their insecure communication systems.

Kyiv is now reportedly in talks with the U.S. to purchase four MQ-1C Gray Eagles (General Atomics), a larger and more capable UCAV the Pentagon would ordinarily consider too vulnerable to survive long in airspace interdicted by Russian air defenses.

Ukraine also fields cruder indigenous armed drones, including the UJ-22, which can drop bombs or launch a UJ-31 munition, and Punisher, which uses an automated targeting system to attack static targets designated by a Spectre drone with three small bombs.

Kyiv also may have converted some of its Soviet-vintage Tupolev Tu-141 and Tu-143 turbojet-powered reconnaissance drones to carry unguided bombs.

On April 10, a Tu-141 apparently went wildly astray into Hungarian and Romanian airspace, crashing near a student dormitory in Zagreb, Croatia, after evading a Hungarian Gripen manned fighter sent to intercept it. Kyiv claimed the Tu-141 was of Russian origin, though Croatian authorities concluded otherwise.

RUSSIA’S NEW KILLER DRONES

“For the Russian military,” Bendett said, “drone use is a key part of its reconnaissance-fire/reconnaissance-strike contours.” That’s a big change from 2008, when the Russian military realized the backwardness of its unmanned ISR capabilities while facing Georgia’s Israeli-built Hermes 450 drones in the Russo-Georgian War.

Afterward, Moscow imported IAI Searcher II ISR drones in its biggest arms import since World War II, made in exchange for canceling plans to export long-range, surface-to-air S-300 missiles to Iran. License-built Searchers, designated Forpost in Russian service, proved their value over Syria and Ukraine in 2014 and 2015, acquiring targets for air and artillery strikes, and providing battle damage assessment and overwatch for ground ops.

After Western pressure forced IAI to terminate the arrangement, Russia’s Ural Civil Aviation Plant (UZGA) developed the Forpost-R clone with indigenous datalinks, software, electro-optical sensors and an APD-85 piston engine. Most notably, it could carry weapons, transforming the surveillance drone into a UCAV.

Russia also debuted the indigenously-developed Kronshtadt Orion (or Inokodhets) MALE UCAV with greater combat capability, explicitely advertised as a rival to the Bayraktar. Combat-tested in Syria in 2019, Orion production was delayed for years until the prototype’s Austrian Rotax engine could be domestically substituted.

After a negligible presence in the war’s opening days, Russia debuted its operational UCAV fleet mid-March, seemingly to counter the preponderance of Bayraktar footage.

Recordings show Orions and Forposts striking command posts, trucks and armored vehicles. Some of the footage, however, seems to exhibit inferior accuracy of its KAB-20L munitions.

Nonetheless, Ukraine’s hard-pressed air force reportedly is using MiG-29 fighters to hunt UAVs, by using medium-range R-27 radar-guided missiles. Russian UCAVs don’t appear to have sustained much attrition, with only one Orion confirmed destroyed so far, compared to 59 Orlan-10 ISR drones confirmed destroyed or captured by June 8.

Moscow’s ability to enhance and expand its UCAV fleet may be curtailed by Western sanctions affecting components it cannot yet substitute domestically. However, many key dual-purpose components used in Russian drones and missiles require aggressive enforcement to effectively embargo.

LOITERING MUNITIONS AND FOREIGN DRONE ASSISTANCE

In some respects a slower-moving species of cruise missile, loitering munitions are endowed with greater endurance usable for reconnaissance and target acquisition, ability to maneuver and even abort an attack, and potential for recovery if no target is found.

Ukraine and Russia have both developed indigenous short-range loitering munitions. The use of Russia’s Zala KUB-BLA kamikaze is confirmed due to the half-dozen that have crashed without exploding or have been shot down. One recording released by Russia shows a KUB missing in an attempted attack on a U.S.-delivered M777 howitzer, its small warhead inflicting little if any damage to the high-end artillery piece. Russia’s larger Lancet-3 munition has yet to be seen in Ukraine despite prior combat tests in Syria.

Both Lancet and KUB-BLA allegedly have controversial autonomous engagement capabilities. The KUB-BLA can use an AI-driven image-matching system to classify targets to attack without human oversight. “[Kub’s] limited visibility in this war so far does not allow for a definitive conclusion if it is or is not using AI,” Bendett cautioned.

Meanwhile, it’s unclear whether Ukraine’s UJ-31 Zlyva/UJ-32 Lastivka loitering munitions mounting an RPG-7 warhead, or prototype longer-range RAM-II and ST-35 VTOL munitions, are being employed operationally.

Overall, loitering munitions haven’t been as prominent in Ukraine as Azerbaijan’s and Israel’s use of Harops kamikaze drones. But that could change.

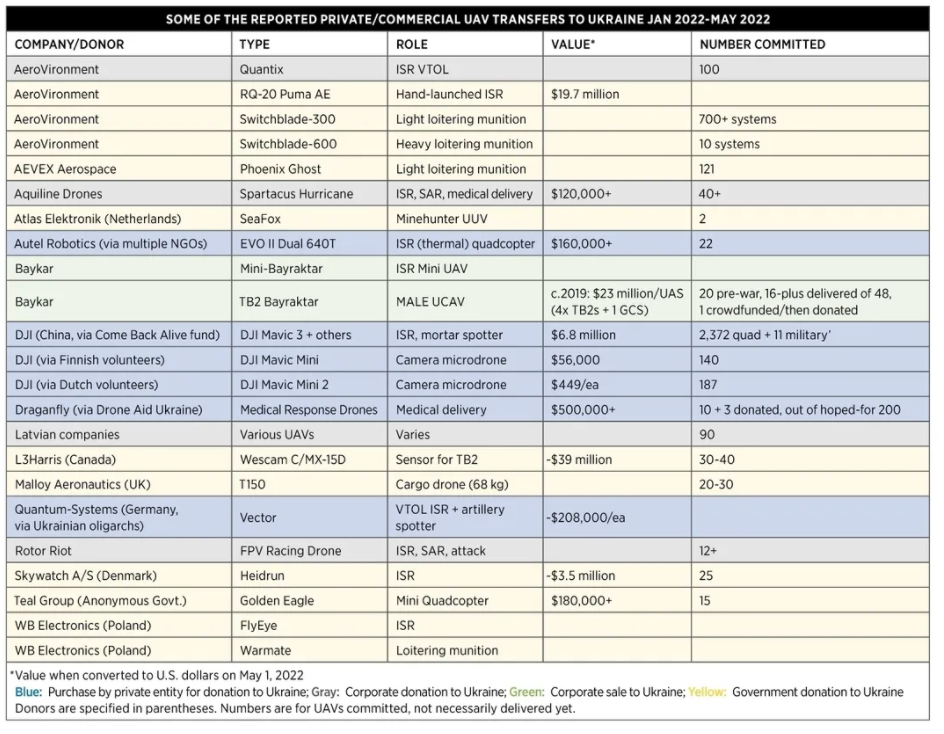

Prior to Russia’s invasion, U.S. drone aid to Ukraine consisted of hand-launched RQ-11B Raven ISR drones—which proved excessively susceptible to jamming. These were supplemented in March by AeroVironment’s RQ-20A Pumas 3s.

But the U.S. also began sending the first of 700 AeroVironment Switchblade 300 loitering munitions and promised to deliver 10 longer-range Switchblade 600 UAS with Javelin-type anti-tank warheads.

In April, the Pentagon revealed it was delivering another loitering munition, heretofore classified, a long-endurance, power-punch VTOL called Phoenix Ghost (see earlier sidebar).

Little footage of Western-furnished loitering munitions has emerged, save for two attacks, one targeting a crude Russian bunker, the other personnel on a T-72 tank. However, the U.S. military is supplying more mature loitering munition capabilities than previously acknowledged.

CROWDFUNDING PRECISION STRIKES

During the 2010s, non-state actors in Syria, Iraq and Ukraine began adapting small civilian drones to deliver lethal attacks, often assisted by supporters outside the warzone. But while these improvised weapons could kill and inspire fear, they did not fundamentally alter battlefield outcomes.

Russia’s war on Ukraine, however, has seen civilian drones achieve greater effects against valuable military targets. Supporters of Ukraine are crowdfunding to purchase and deliver drones to Ukraine’s military. Russian civilians have adopted similar methods to support Russian troops.

“This is the new way of war—belligerents can easily get their hands on this COTS technology and put it to use, even if such DJI drones can be vulnerable to countermeasures,” Bendett wrote. “Professional militaries must be ready for this persistent challenge, and train to identify, jam and counter such sUAS, or risk being targeted.”

The affordable DJI Mavic 3 drone has proven a popular donation, though Ukrainians claim (and DJI denies) that Russia has been given superior access to DJI’s AeroScope drone tracking system, allowing its forces to trace paths back to the operator’s position. (For more on this, see the Blue cybersecurity piece that appears later in this section.)

A quasi-donation of consequence is the Starlink satellite internet service from SpaceX (admittedly one-third funded by U.S. AID.) This has been vital to drone operations of Aerorozvidka, a former civilian organization reintegrated into the Ukrainian military in October 2021 that is reliant on civilian donations of drones, spare parts and 3D printers.

The unit reportedly deploys 50 drone teams performing roughly 300 sorties per day. First, its civilian UAV locate and observe Russian positions and troop movements, integrating findings into a real-time tactical “map” used by Ukrainian artillery units for planning fire missions.

Then at night, when Russian units are immobile and visibility is poor, Aerorozvidka strike teams creep within range on quad bikes and deploy R18 octocopters or Punishers modified with infrared cameras to execute point attacks, dropping mortar shells or shaped charge anti-tank grenades.

Allegedly, Aerorozvidka teams helped locate and pin down with artillery Russian paratroopers landed at Antonov Airport in the war’s opening hours. Later, they crippled supply trucks and lead vehicles of Russian columns, slowing the advance on the Ukrainian capital.

Admittedly, gravity bombing doesn’t always hit, and small munitions sometimes have limited effect. But several videos show precise delivery of anti-tank grenades destroying or damaging even main battle tanks with direct hits to thin top armor.

The unit’s capabilities are constrained by limited funding, foreign export controls, prevalent jamming and Russia’s use of HF/DF methods to geolocate Ukrainian drone teams. However, given the demonstrated ability of these cheap civilian platforms against armored targets, militaries may show renewed interest in their application.

THAT’S BAIT! DRONE DECOYS VS. AIR DEFENSES

In the opening hours of the war, Russia dispatched pulsejet-powered E95M target drones over Ukraine, not to attack, but to be attacked by air defenses, exposing Ukrainian radars and launchers to be located and destroyed by Suppression of Enemy Air Defense (SEAD) strikes. The E95M can be fitted with Lunenberg lenses to increase radar cross section to 8m2, comparable to that of a fighter.

This is hardly a new tactic: in 1982 Israel used drone decoys in Operation Mole Cricket 19, which destroyed Syrian air defenses in Lebanon in one day without loss of manned aircraft. However, it reveals drone decoys are now seeing application by actors with limited prior SEAD experience, such as Azerbaijan, which employed a remote-control An-2 biplanes as decoy targets in the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war.

Russia’s drone decoys reportedly helped inflict bruising losses on Ukrainian air defenses in the opening days of the war, but subsequent, sporadic SEAD efforts failed to deliver a knockout blow.

Ukraine may have used Tu-141 drones in the same role. Furthermore, Kyiv alleges drone decoys played a role in the humiliating sinking of Russia’s Black Sea flagship Moskva. Supposedly, a Bayraktar drone diverted the cruiser’s air defense operators away from Neptune cruise missiles approaching from another vector.

Experts are skeptical of this claim, as even Moskva’s outdated defenses should have been able to track multiple targets. Still, a TB2 may have helped locate the cruiser for targeting by the land-based battery.

HAVE UNMANNED SYSTEMS “DISRUPTED” RUSSIA’S INVASION OF UKRAINE?

While the unmanned platforms flying over Ukraine are hardly unprecedented, their use in a high-intensity conflict between large states truly is. Ukraine has deployed armed drones to execute bold and destructive attacks more persistently than many thought possible in the face of Russia’s seemingly formidable air power and air defenses.

UAV have had even greater impact locating targets and adjusting fire for lethal artillery fires, and helping forces carry out or evade ambushes. Furthermore, imagery from unmanned systems has been critical to shaping global perception in favor of Kyiv’s military prospects. Both civilian and military unmanned systems have risen in prominence as a form of military assistance offered by both state and non-state actors.

Russian use of UAVs has also been effective, but not on a sufficient scale to achieve desired outcomes. Given heavy losses to both sides’ manned aviation and the relative affordability and resilience of armed drones, both Kyiv and Moscow will emerge motivated to accelerate adoption of low- and high-end UAVs and UCAVs.

Arguably one of the most surreal images of the war, with real shades of 1984’s Terminator, is a recording from the perspective of a low-flying Ukrainian drone effortlessly keeping pace with a Russian soldier fleeing in terror. The UAV is apparently unarmed, and the soldier makes it back to his unit concealed in a roadside revetment. Afterward, the newly observed unit is reportedly hit by an artillery bombardment.

Experiences from Ukraine’s war of resistance drive home that relatively inexpensive unmanned systems can have substantial impact even in a high-intensity, intimate-scale, interstate conflict.