This article is all about what the services are doing with their drone programs. I don’t have the space to cover the entire DOD in a column, so I’ll start the conversation by covering the Air Force, Navy and Marines. The Army gets its own article elsewhere in this issue because its drone program might just get America back into the small-drone business after the Chinese seized about 80% of the American market. The bottom line is: drones are here to stay because the great drone culture wars in the services are largely over. Indeed, the big question about drones is no longer whether they’re safe and effective; it might just be whether we still need manned aircraft.

First up is the largest and most influential drone program in the DOD, the U.S. Air Force (I try not to pick favorites, but if I did…).

AIR FORCE: STEALTHY, SWARMING AND STEADFAST

Pardon the history lesson, but history begets experience and experience defines culture. Culture, not technology, logic or even funding drives how a service will fight.

The American tragedy of 9/11 was a turning point for the Air Force. It was the first conflict where drones weren’t just a means to avoid combat losses, but the best and probably only choice for a new category of target—the “high value individual” (HVI). It was also the first time drone technology allowed airmen to fly them beyond line of sight (BLOS). Before 9/11, Air Force drones either had to stay within roughly 50 miles of a ground control station or 150 miles from a drone mothership for a remote pilot to control the drone. General Atomics’ MQ-1 Predator had a satellite communications data link, allowing pilots to be thousands of miles away from their drones. General Atomics used the weight saved from going unmanned to add incredible endurance to the Predator; it flew about 20 hours without refueling. The endurance and BLOS capability of the Predator allowed the Air Force to stalk HVIs for weeks or months for the first time in history.

The Predator’s success in Afghanistan sparked the great Air Force “drone culture war,” which was made worse as the demand for the Predator grew from the single 15-hour orbit I supervised after 9/11 to the 65-plus orbits the Air Force flies today. Drones were easy to ignore when they were a novelty. They became impossible to ignore when the president personally asked for more of them. Intelligence officers like myself loved drones from the start but Air Force pilots hated them at first. Most pilots doubted drones could perform as well as manned aircraft and some were afraid drones would do better than manned aircraft, threatening pilot jobs. Compounding the problem, the tremendous demand for drones drove the Air Force to press-gang pilots into flying them, creating a giant pool of pilots who hated drones because it cost them cockpit time. Worst of all, drones DID cost the Air Force manned fighters as the Department of Defense forced them to close down F-16 and F-15 units to fly more drones. Was that a bad thing, or was that progress in a changing world? Daunting questions from history are easily answered with the wisdom of the future.

The staggering battlefield successes of Air Force drones in Southwest Asia and the decision to create an Air Force remote pilot career field eventually ended the Air Force drone culture war. No one could argue any longer against the success and safety of Air Force drones, but they lacked a dedicated community to support them. Once Air Force leadership created a separate career field for remote pilots, drone-remote cockpits became filled with airmen eager to be there. A new culture was now encouraged to flourish, and the Air Force became convinced drones were their future. The doubts of the past from Air Force leadership through the ranks are for the history books now.

Stealthy: With the drone culture war over, visionaries in Air Force acquisition, led by Randy Walden in the Air Force Rapid Capabilities Office (RCO), felt free to authorize production of drones using the Air Force’s crown-jewel technology—stealth. The fact that the RCO thought drones were reliable enough to risk stealth tech over enemy territory speaks volumes about Air Force drone plans. Indeed, even the loss over Iran of the only stealth drone the Air Force has ever talked about, Lockheed’s RQ-170, hasn’t halted plans for additional stealth drones. The Air Force might wait decades before disclosing the “fact of” additional stealth drones, let alone details. Tantalizing open press leaks and observations by aviation zealots outside Area 51 yield plenty of rumors about several subsonic stealth drones and an “SR-72” hypersonic vehicle from Lockheed. We won’t know the truth for years, but from the limited info we know, the Air Force is flying something stealthy. And unmanned.

Swarming: If the Air Force can’t surprise enemies with stealth, it will swamp them with swarms of low-cost drones. Assisted by DARPA and the Navy, the Air Force is researching both small- and medium-sized drones. When the Air Force says “small” they mean it. Drones such as the MIT Lincoln Lab’s Perdix drone will fit into flare/chaff tubes carried on all Air Force fighters. Fighters will fly close—but not too close—to enemy radars and release Perdix. The Perdix will organize themselves, then fly towards enemy radar, where they will assume a formation designed to counter that particular radar and jam it from close range. Other Perdix will carry chaff and, if I were in charge, some would have explosives to harass enemy missile crews.

The Air Force is also experimenting with medium-sized “attritable” drones delivered by drone motherships in the Air Force/DARPA Gremlins project. “Attritable” is an Air Force word meaning, “We’d like to use this aircraft several times, but no one is getting court-martialed if it gets shot down.” The Gremlins project uses a C-130 cargo drone mothership to air launch and recover Kratos Gremlin drones. The idea is to use the mothership to launch the Gremlins just outside enemy air defenses, eliminating the need to create and deploy large, long range drones to fly from bases outside enemy ballistic missile range. Air-launched/recovered attritable drones may or may not use swarming tactics to survive in enemy airspace because sometimes it is best to send Gremlins in one at a time to run the enemy out of missiles before following up with the main package for the final act. If the Air Force loses a few, well, no one gets court-martialed.

Steadfast: Each February brings two great American traditions: Mardi Gras and Air Force Proposed Cutting of the MQ-9 Reaper Combat Air Patrols (CAPs). Just like Mardi Gras, the Proposed Cutting of the MQ-9 CAPs always starts with the best of intentions and always ends with regrets and guilty looks. This year, the Air Force tried to cut 26 CAPs to fund more “high end” weapons such as the F-35 and hypersonic missiles. Just like every year, they had to abandon the effort due to roars of disapproval from the combatant commands, the secretary of defense and the CIA. The MQ-9 may not be considered as stealthy as it once was in its early years, but it remains supremely effective and one of the most safe, steadfast, experienced drones in the inventory. There is something to be said about gaining wisdom with age, even when it comes to drones.

I often call the MQ-9 the DC-3 of the drone world. Like the DC-3, it was invented early in its aviation era. And, like the DC-3, it’s survived for decades by mutating into a wide variety of roles. The DC-3 started life as an airliner, became a troop carrier in WW II and ended up as our first gunship. The MQ-9 started as a reconnaissance drone, pivoted to a fighter-bomber and now may become a carry-all for airborne radars, communications relay and missile warning.

General Atomics has been very effective in innovating the MQ-9 into a flying “Mr. Potato Head.” Want to fly higher and farther? Swap wings for the Extended Range version. Icy weather? Equip the anti-ice wings. Need comm relay? They have a pod for that. SIGINT? Pod. AWACS radar? Pod. JSTARS radar? Pod. Maritime surveillance? Pod. They love that kind of stuff. Drones with freakin’ laser beams (for comms)? Pod. Someone shooting back? Put some weapons pylons on that GA crammed with chaff/flares/electronic countermeasures gear and a radar warning receiver. Gotta fly in civil airspace, needing to sense and avoid airliners? Send the maintenance guys out to swap the radome and plug in a radar. In the rain. Even if the AF convinces DOD it doesn’t need MQ-9s in the counter-terror fight, continued successful, transformative plastic surgery by General Atomics will keep this wise old drone around for decades.

The other Air Force steadfast drone, the RQ-4 Global Hawk, isn’t aging so well. The Air Force wants to kill most of the Global Hawk program by eliminating the Block 20 (comm relay) and Block 30 (reconnaissance) versions, retaining only nine Block 40 (moving target indicator radar) Global Hawks. This is the second time the Air Force has gone after the RQ-4 and it may be successful. This time, the Air Force was savvy enough to keep the U-2 alive to satisfy the California congressional delegation while leaving the Block 40 alive to keep the North Dakota delegation happy. Northrop may not fight the decision because the company doesn’t want to jeopardize future buys of the B-21 stealth bomber. Not to worry though—General Atomics has pods to cover all those cancelled Global Hawk missions.

NAVY DRONES: NOT IF IT IMPACTS OUR F-35

Navy culture isn’t as monolithic as the Air Force’s. The Navy splits into surface warfare, subsurface warfare and naval aviation camps—and each camp has a different view of drones. You’d think naval aviation would take the lead on drones, but like Air Force fighter pilots in the past, impacts on manned fighter numbers makes them leery. Carrier strike aviators are the dominant force in naval aviation, and they saw what the MQ-9 did to Air Force F-15 and F-16 numbers. The MQ-9 never affected the Air Force F-35A program because it had the fewest technical challenges with the most foreign sales to reduce unit cost, but the Navy’s F-35C program continues to struggle and has no foreign sales to help buy down costs. Plus, it’s a short-ranged stealth fighter that launches from decidedly unstealthy carriers that must stay well outside enemy defenses to survive. A stealthy carrier-borne drone would make too much sense compared to the F-35C. Carriers could hold double or triple the number of drones than F-35s, their range would be four times that of the F-35C and carriers would only have to cycle (launch/recover) drones every 12-24 hours instead of every 90 minutes for manned aircraft.

Hence, it was only after excruciating pressure from multiple secretaries of defense that the Navy finally bought a stealthy carrier drone, specifically, a stealthy aerial tanker carrier drone. No kidding. Not a fighter. Not a bomber. Not a reconnaissance drone. A tanker. Why? Well, to refuel all those stealthy F-35Cs to give them enough range to keep their carriers safe. True story. Boeing’s MQ-25 carrier drone is a great aircraft and, luckily, Boeing designed it to rapidly change into a reconnaissance strike drone if the Navy needs it. But trust me, there will be no MQ-25 transformations until the F-35C is cleared to fly.

The other half of naval aviation is comprised of the shore-based aviators, nearly all of whom fly sub hunters or reconnaissance aircraft. They’ve been much more culturally open to drones because their manned aircraft, the P-8 Poseidon, breezed through test and sold well on the international market. Once it was clear the P-8 was a success, Navy shore-based aviators supported a naval version of the Air Force Global Hawk, the MQ-4C Triton. Unfortunately, the MQ-4 is a much more complex aircraft than the Global Hawk and it hit some snags, forcing the Navy to put it on acquisition hold until Northrop fixes the problems. I’m not taking bets on survival, particularly after the Luftwaffe cancelled its Triton program in favor of a Bombardier. Again, not to worry, because the MQ-9 has a pod for this mission also.

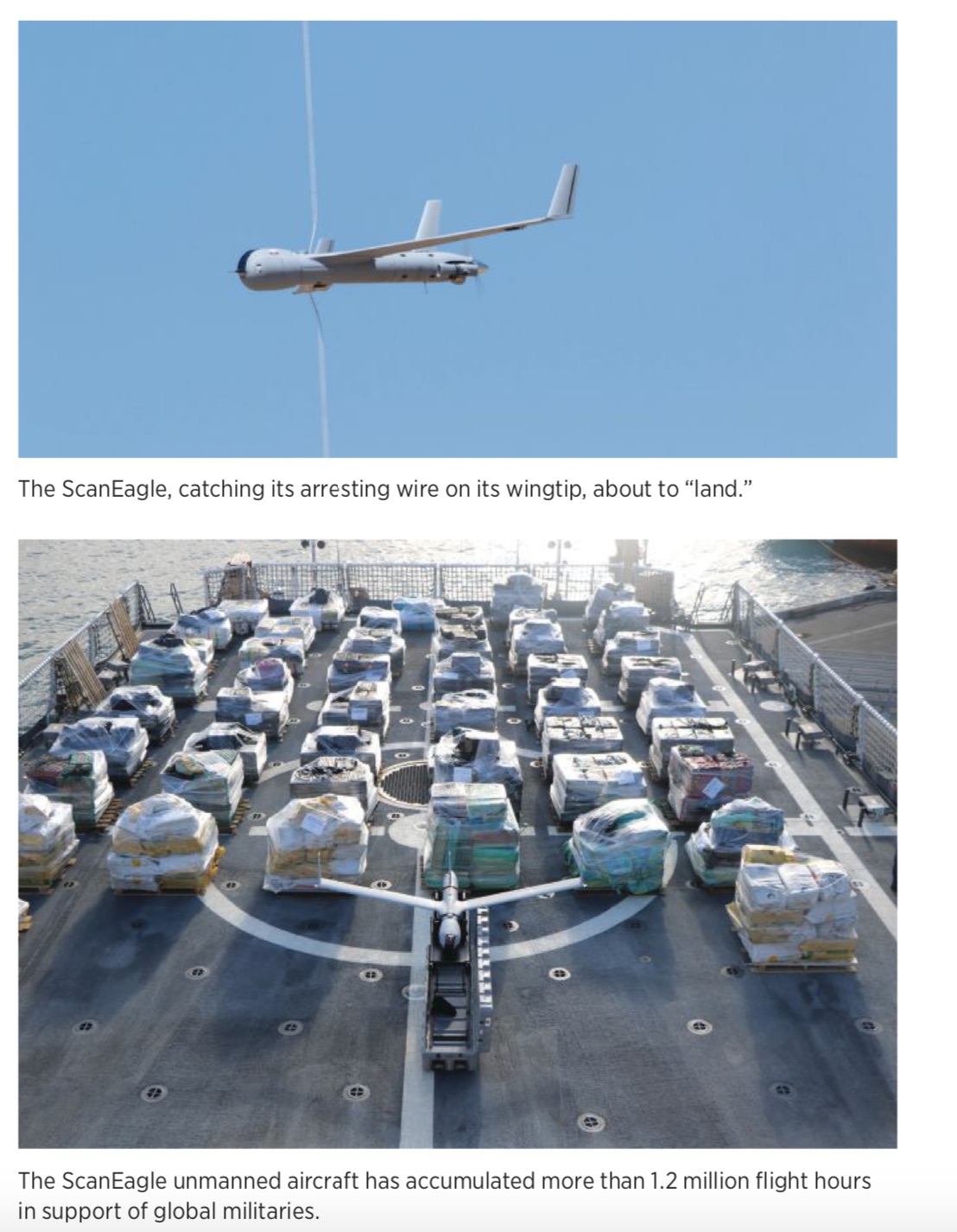

The Navy’s oldest tribe is, ironically, the most open to drones. The surface warfare community has been around since about 1210 BC (I went to Navy Staff College; they teach you that) but it embraces drones because they enhance capability at low cost and because these warriors smartly don’t worry about losing cockpits to drones. Hence, the Insitu ScanEagle/Integrator and the Northrop Fire Scout are serving safely for the foreseeable future.

MARINE DRONES: NOT INVENTED HERE IS FINE BY US

The Marines survive on a tight budget by making the other guys pay for development and saving development cash for things only the Marines would fund. Hence, the Marines went all in on the least logical F-35 variant—a stealthy, very-short-range vertical takeoff jet that flies from very unstealthy mini-carriers to escort even less stealthy helicopters/landing craft. Against all odds, the F-35B survived and—surprise—Marine aviators are now interested in drones. That’s a good thing. Marine aviation had a positive experience with leased General Atomics MQ-9s in Afghanistan and the service is now in final negotiations to buy the MQ-9B variant used by the Royal Air Force. In classic Marine style, it’s managed to swoop in and take advantage of development costs borne by not one but two Air Forces. Gotta give them a “credit where credit is due.” Notice they picked the MQ-9: If there’s one thing the Marines like more than free stuff, it’s stuff that can do all kinds of stuff. I foresee many, many pod sales to the USMC once it gets its Mr. Potato Heads.

Like the Navy, the oldest Marine community—the Riflemen—had no hesitation in adopting drones. Marine Riflemen repurposed the Navy Insitu ScanEagle to land operations way back in 2004 (still seems like just yesterday sometimes in drone years), improving on it with the Blackjack variant (Integrator in the Navy) in 2011. The Army hand-launched Ravens and Navy SEAL Pumas made it to Marine Riflemen very quickly. These systems are securely funded; DOD can have them when they pry Marine Riflemen’s cold, dead fingers from them. Unless, of course, in waiting the Navy or Army develop something even better for their pickins.

AND THE ARMY?

That branch is in a genuine dilemma because it desperately needs a new tank, armored personnel carrier, attack helicopter—and to fix everything two decades of combat has broken. Fitting drones in there somewhere will be tough, like fitting Mardi Gras into a busy work month. But of all the services, the Army knows how important drones are to protecting our troops. And let’s hope Mardi Gras 2021 will return to excellence—hope to see y’all there next year!