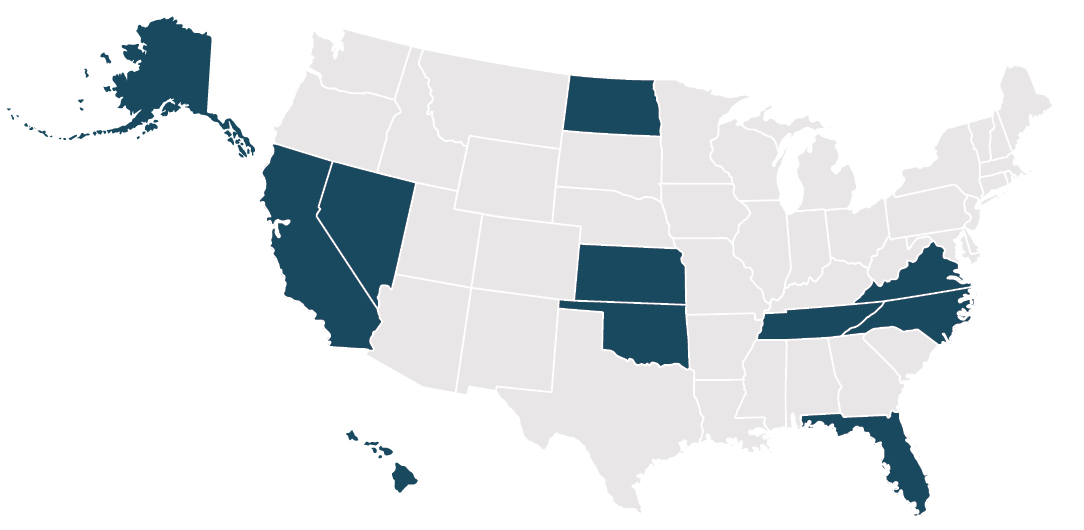

10 teams were chosen out of the 149 that applied.

Drone applications ranging from finding feral hogs to delivering aid to heart attack victims are now under fast-track development as part of a new federal program to break through the technical, regulatory and societal barriers holding back the unmanned aircraft system (UAS) industry.

American companies are known for using ‘tiger teams’—an approach to problem solving created by NASA—to develop new technology and tackle big challenges. Now the White House is adopting this concept to work out how to integrate drones into the national airspace. They are betting that 10 teams of the new Integration Pilot Program (IPP) will be able to prototype the next phase of the entire drone industry.

To find success, the teams and their roughly 200 partners will have to design new hardware, upgrade their software and stretch the capabilities of communication and tracking systems to launch new applications chosen, in large part, for the challenges they entail. And, though they can apply for a 1-year extension, officially the Department of Transportation has given them only two years to get it all done.

Developing the applications, though, is about much more than rotors, batteries and sensors. To achieve their commercial potential the teams must win permission to fly from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), which is going to require them to make the case that their technology is safe enough to operate in the national airspace. What’s different is the FAA is not waiting to see what the teams come up with but is directly involved from the beginning. The agency is assigning staff to every team to both help them work through the requirements and to learn along with them as things progress. The goal of the regulators is to use this view into the day-to-day guts of development to help craft practical new rules for an industry straining to be cut loose.

Moreover, by design, the teams are led by state, local and tribal organizations—effectively giving the general public a huge say in how things are done. These government organizations are hoping to gain an economic leg up for their communities while finding better solutions for local problems like traffic backups. For them to succeed, however, they must not only support the teams and the FAA, they must bring their residents into the process, winning their constituents over to the possibilities while ensuring the teams address real concerns like noise and privacy.

Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao (left), shared the stage with members of Congress and team representatives during the May 9 announcement. Photo Courtesy Department of Transportation

Safety First

One thing the public probably won’t need to worry about too much is safety. Though the FAA is clearly enthusiastic about IPP it is not easing up on its safety requirements for unmanned aircraft systems (UAS). It’s a challenge though, said Earl Lawrence, executive director of FAA’s UAS Integration Office, because many of the teams do not have roots in the aviation industry and therefore don’t really understand what is needed.

“We’re used to dealing with …the aircraft manufacturer or the operator,” Lawrence told Inside Unmanned Systems.

To help things along, Lawrence said, the FAA is assigning a program manager to each of the team leads who will be “their partner from the FAA for the entire time that this program goes on.” That manager will guide the teams as they file for waivers and permission to fly as well as deal with issues like getting frequencies or the safe handling of things like lithium batteries.

“The program manager will be our point of contact for all questions related to IPP and they, of course, will be leveraging a team of experts at the FAA headquarters and other sites. So we have one point of contact that we will be able to work with,” said Catherine Cahill, the director of the Alaska Center for Unmanned Aircraft Systems Integration at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. “The person they selected for us has a lot of experience with Alaska. So they picked the perfect person to be able to work with us on this.”

Those additional experts, Lawrence said, will also serve as conduits for bringing information back to support rule making and to be able to take what’s learned in one area to inform another. The team from the Lee County Mosquito Control District, for example, is working on drone-based applications for low-altitude spraying to control mosquitos and hyacinths. The FAA expert can help them build on what’s already in place for spraying from manned aircraft. What the expert learns from the team could also inform new rules for drone-based spraying of farm fields for agricultural pests.

An Intel Falcon 8 inspects a flare stack. Photo Courtesy Intel

Cutting Edge

The teams were chosen based on the criteria in the initial screening information requests and other published sources like the presidential memorandum, Lawrence said. Among those criteria were environmental and economic diversity and the cutting-edge nature of the problems each team chose to tackle.

Beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) and flights over people, for example, are critical for package delivery—a goal of seven of the 10 teams.

North Carolina and San Diego are trying to speed the processing of blood tests and other medical samples by taking them out of the hands of expensive couriers and putting them on direct-to-the-lab drone flights. Flirtey is working with four of the seven teams pursuing rapid delivery to get defibrillators to heart attack victims. In Reno, where the firm is based, Flirtey has partnered with Federal Express to put their drones in FedEx stores. When a call comes into 911, both an ambulance and a drone are dispatched.

“Based on our analysis, just in the city of Reno, one Flirtey delivery drone has the potential to save at least one life every two weeks on average when that drone is prepositioned, carrying a defibrillator, and plugged into the 911 network,” said Matthew Sweeny, Flirtey’s founder and CEO.

Other delivery services are about cost and convenience. Holly Springs, North Carolina will experiment with using a drone to deliver food and goods from a mall to the surrounding area. San Diego and Uber are planning to partner with food chains to test drone-based food delivery.

“I think the future might be flying burgers,” said Harrison Pierce, San Diego’s homeland security coordinator.

The real opportunity is in the last mile said Sweeny, who believes Flirtey could eventually expand to more general deliveries

“It varies,” Sweeny said, “but approximately 50 percent of the cost of delivering a good to someone’s home is spent in the final leg of the delivery from the storage distribution center to your home. And consumers want last mile delivery that is faster.”

UAS traffic management in Virginia. Photo Courtesy Virginia Tech

BVLOS is essential for other applications like search and rescue and rapid deployment of cameras to emergencies so first responders better know what they will encounter.

“We think that we can use some drone applications to get to the scene of the crash quicker than we can physically and get information back to our EMT (emergency medical technician) or to the hospitals. That can help save people’s lives,” said Tom Sorel, director of the North Dakota Department of Transportation. It might also be possible to get medical equipment to the scene more quickly using a drone, he said.

The team lead by the Choctaw Nation wants to do emergency response and search and rescue—including finding ways to use drones in bad weather. They also want to deploy drones for herd management, especially for large ranches where cattle may be grazing in unfenced areas. They have another problem they hope to reduce with BVLOS, night flights and infrared sensors—locating feral hogs.

“They are very mean,” said James Grimsley, founder and president of DII, a Choctaw team partner. “They’re also very destructive. They just devastate areas and they can actually be deadly to humans.”

Memphis and FedEx have multiple plans for their BVLOS operations.

FedEx is headquartered in Memphis and has its global transfer hub at the Memphis International Airport. The airline wants to use drones for inspecting its planes and for bringing small parts from the warehouse to airplane mechanics using a pre-established flight corridor.

“The drone is flying above the traffic and obstructions so it can move much faster than a mechanic who has to drive back to the warehouse,” said Scott Brockman president and CEO of the Memphis-Shelby County Airport Authority.

Brockman wants to work the drones into the regular traffic control system of the airport so they can safely be used to inspect taxiways, runways and the airport’s perimeter fence.

“I’ve got a 10-foot security fence around my 5,000-acre airport,” Brockman said. “Now within that security fence I have various perimeter incursion detection systems, I have cameras, and then a minimum of twice a day I have people that drive the entire fence line—very labor-intensive.”

The Memphis team also wants to use drones to document the contours of the Wolf River and study the water in the river and in the watershed that surrounds it. He said they want to use a drone to collect the needed water samples, something that may require the invention of new hardware.

“That’s what the program is about” Brockman said. “It’s a pilot program to see if we can develop that.”

Draganfly hardware was part of tests done in North Dakota. Photo Courtesy North Dakota Dpt of Transportation

Room For Change?

Lawrence said the teams would have the opportunity to learn from each other through frequent get-togethers and required reports. Those reports will be available to the public as well, he said, though it is unclear what the schedule would be for their release. There will also be white papers and reports on the teams’ progress at the annual FAA Symposium.

“I can’t imagine us having our annual symposium next year and not having some type of forum on specific operations and a report out of how they’ve done,” he said

Those who want to be more directly involved may have an opportunity later in the year. The teams have to stay focused on the plans they submitted to the FAA, Lawrence said, but added there is still room for change.

“Now with any project, when you get into implementing those things; you learn things, you find things out,” Lawrence said. “You may have to add a partner—you may have to change a partner or something like that in order to be successful in that operation. Obviously that will occur.”

According to Serol, the teams have been told they need to hew close to their submitted plans until August. After that point, however, it will be possible for them to make adjustments in their partnerships and plans.

“Right now this project is such that this process is so formalized by the federal government that it’s very important we stay within the boundaries of their program,” said Bob Brock, director of aviation for the state of Kansas. “However, we’ve established a site to be able to allow people to express interest for when the opportunity arises, and that window is open, we’ll certainly be prepared to partner at whatever level is appropriate for people to create a mutually beneficial relationship.”

Lawrence made clear, however, that the FAA would hold the teams to doing what they said in their initial applications.

“The baseline is what they applied to do and we’re starting there. And just to add things—I think my professional evaluation of it is, they will find it very challenging to—in two years—to do what they proposed let alone add anything else.”

Resources

It’s also possible that there will be another round of teams chosen, Lawrence said, but it’s too early to know.

“Adding more (teams) as part of the program …that will be really based on resources and we are concerned—not that we won’t succeed but (that) we don’t know how much total resources it’s going to take just to work with the 10 we have now,” Lawrence said.

That does not mean those organizations that did not get selected can’t keep going. According to Lawrence, at least 50 percent of those who applied for the IPP were hoping to work on things they were already able to do under the Part 107 regulations or as a public operator.

“They simply didn’t know the rules,” Lawrence said, “or they were looking at one of the barriers that was still out there”—the time needed to get airspace approval.

Lawrence said the FAA was catching up with the industry’s desire to move faster, pointing to LAANC (the new low altitude authorization notification capability), which is set to be available in some 300 airports by fall.

“With LAANC going nationwide this year that opens up so much airspace,” Lawrence said. “That’s an existing system where they don’t need a special public COA (Certificate of Waiver or Authorization), which is, as you know, an airspace approval for their local area, and they can take full advantage because the other rules are already there.”